You Are That Person Who Has Left

• Yiyun Li • October 1, 2013

The thought of interviewing Tom Drury and Yan Lianke with a set of similar questions occurred to me because in an ideal world, without geological and language barriers, I would have liked to listen to a conversation between the two.

I’ve been an admirer of Tom Drury’s work for years. A long time ago, I wrote him a fan letter and confessed that he was one of the two living authors I would like to meet. Characters from his trilogy set in Grouse County, Iowa (End of Vandalism, Hunts in Dreams, and Pacific), have become part of my consciousness when I read and write. I have also been paying attention to Yan Lianke’s work for the past decade. His novel, The Dream of Ding Village, about the AIDS epidemic in Henan Province is one of the most important novels coming out of China in the past twenty years.

Much of Drury’s work is set in Iowa. All of Yan’s work is set in Henan Province, in China’s heartland not unlike Iowa. Both writers grew up in rural areas. Yan’s journey took him from his hometown to Chinese army and eventually to Beijing, while Drury’s took him to the east coast, and west coast and now back to New York City. Both worked in journalism before becoming writers. Both, in person, are unpretentious and thoughtful.

The interview with Yan Lianke took place in a hotel in Berkeley. The interview with Tom Drury took place through emails. Ideally one would like to hear back-and-forth between the two authors, but it’s interesting to see, without their talking to each other directly, where the two perspectives diverge and coincide.

Home

Yan: [Of Beijing and Song County,] it’s an embarrassing position for me, suspended between the two. When you go back to the village, people don’t regard you as one of them. You are, to them, that person who has left. In Beijing no one considers you as part of the city, either. Legal residence doesn’t make you a real person there. Beijing is only a place where, after years of struggling and some achievements, you’ve earned the right to stay.

No, I don’t write about Beijing. You can’t write about a place unless you’re confident about every single detail. I don’t think I can ever understand the metropolitan residents. Anything you write has to have a life rooted somewhere—it’s glib to say so, but truly, for me, every word I write has to be connected to the earth in Henan’s countryside.

Drury: [Are the two worlds—Grouse County and New York City—different?] Yes, one being fictional and the other real. They feel like separate spaces because one is in my head and the other outside my windows. Grouse County doesn’t really represent a single time point. It’s more like many of the times I’ve known brought together.

I feel free though to take what is useful (conversations, images, situations) from my life in New York for the fiction I’m working on, wherever it is set. This free mix of elements from different places and times has always been part of my writing.

Probably where I live is more real, having materiality. But I may be closer to the one that occupies my mind when I’m writing. In the case of Grouse County, I’ve worked on three different books about it, not continuously but over a period of almost 25 years. That’s longer than I’ve lived in any one place.

Homecoming

Yan: I have conflicted feelings about going home: I go two or three times a year, but dread it too. Yes, it’s all for the blood connections: my mother is alive; my sisters and their husbands live in the countryside; my brother retired as a county postal worker. But when I’m there I don’t feel close to them. Still, that’s your home. I’m in my fifties, and I’ve told my son this: after I die—no matter when and where—he’ll have to send my body back there.

People in my home village know I’m a writer, but my work matters little to them. I can’t ask even my siblings to read a single book written by me. They like to think of me as someone who can solve their life problems, but who am I to solve anyone’s problem? Here’s an example: when I go home, the county head of the Communist Party would visit me, so that a reporter can write it up for the newspaper. Once he said: “Lianke, if you need any help, come to me.” After he left, all seventeen families in the village came to our house, saying that they needed a road paved from the village entrance to the main road, and the county head had promised anything I asked. I couldn’t make them understand that it was only an empty promise. In the end, I bought the cement and hired workers to pave the road so the villagers would stop sitting in our house.

Drury: [Going back to Iowa is] a little like going back in time. I feel that way when I drive by places I’ve lived in Providence and Somerville, Massachusetts, as well. It seems surprising though of course it shouldn’t that the places are still there when I have gone. It’s a confusion of place and person. Ghosts probably get the same feeling.

I used to ask my mother to read the books before publication—she was an excellent copy editor and her letters influenced the way I write. She wrote on a Remington typewriter in simple declarative sentences that created images with zero attempt to embellish or be writerly or any of that. One that I recall told how she had taken a walk along the railroad tracks north of town and seen the water from an irrigation system falling on corn leaves. I could see the whole scene and hear the sound of the water and feel the sunlight emanating from that sentence. Her typewriter was like the one below. My siblings and I wrote our high school papers on it. In those days you had a family typewriter, or we did anyway.

My mother died in 1999, so now I ask my siblings to read the books, and they’ve been kind enough to take up the challenge. After reading my new book, my sister wrote, "It makes me smile, and is a comfort to read your writing. It's this comfort, that I don't find with other writers ... and I wonder if it is your writing, or you that I relate to?" I don't know the answer, but I understand her comment about comfort. In my books the circumstances may be dire and strange but things find a balance in the end. Sometimes I feel that I don’t write about the world as it is but as I want it to be.

I was once told that the way the people in my hometown read The End of Vandalism was flipping through it very quickly, scanning for objects they recognized, and saying, for example, "A blue car! I had a blue car!" I don’t know if they like reading my novels apart from these little recognitions. I would imagine there are other books they would rather read.

Becoming a Writer

Yan: The entire reason [to become a writer] was to leave home. When I was sixteen, I felt overwhelmed by watching my people—my great-grandparents, my grandparents, and my parents toiling and living and dying on that poor land. It was mixture of extreme emotions—exhaustion, hatred, disgust, despair—that made me want to leave forever. At the time you would read in the newspapers that so and so was given a legal residence in the provincial capital because of a publication in a local magazine; so and so became famous for publishing a story in a national magazine. I thought I must become a writer, too.

Drury: Because I loved books. When you grow up in a rural area and don't get out much, you really appreciate the power of writing to create worlds and situations you can't experience directly. It's very appealing and I wanted to try it myself. And I was always writing, in a way. When I was very young I would draw comics. Or I would move toy people around and provide the dialogue aloud. Just whatever outlet the imagination could find.

Writing Fiction

Yan: The most difficult problem that we [contemporary Chinese writers] face is that we can’t write the realities of our country into fiction and make them real. When Yu Hua published To Live, people criticized it as unbelievable, and he argued that everything he put into that story had happened. But is that a good argument?

A few days ago, the newspaper reported that there were ten thousand dead pigs floating down Huangpu River [near Shanghai], and the government said that they were not harmful to the environment. I imagine that if Yu Hua wrote this into a story, he would have done it in a way that makes it even more absurd. I would rather write it plainly so it’s less absurd. Even then it is a challenge, because China is becoming such a strange place, and its reality is becoming unreal, and beyond western readers’ imaginations.

Drury: [Regarding] ornate vs. plain writing as well as fictions that overtly say “I’m invented” vs. fictions that say “Here is something that happened.” I think that plain writing which seems to portray events happening to people has a purpose, and that purpose is to bring those events and people into being, or our perception of being, which is pretty much the same thing. Let the word equal the thing and maybe it will. Borges has a relevant quote: “[A]s time goes on, one feels that one's ideas, good or bad, should be plainly expressed, because if you have an idea you must try to get that idea or that feeling or that mood into the mind of the reader.”

Fiction and its Host Country

Yan: I strongly believe that the most urgent task for a Chinese writer is to escape the shadow of magic realism. Take the pigs’ situation as an example: you can write it with magic realism for western readers, but that’s not the real story. The real story is, when the government tells the people that these pigs are harmless, first, nobody believes the government; second, nobody deems an alternative explanation necessary. If an official is caught for embezzling a hundred thousand yuan, it would look as a corrupted case to the west, but we would laugh, as though his real problem is not his corruption, but his foolishness of being caught. These logics—intrinsic to China—cannot be written with magic realism. Every Chinese writer of my generation is baffled. Do we go back to realism? Or do we discover something for ourselves? Sometimes the absurdity of a situation is only accessible to its Chinese readers. How can we make western readers understand our work?

The realism in Chinese literature reached its height in 1984, with Lu Yao’s Life. But if you look at that book, it’s not much different from The Red and The Black. We are writing under the influence of Stendhal; we are repeating what he did over a hundred years ago, and haven’t done better.

Drury: My work is not really meant to portray the "heartland [or any land] as we’ve been led to understand it.” I'm not trying to say this is how a place is, or how the people who live there are, but how some people could be, in a particular way that makes me want to write about them. The place is a stage on which all kinds of things can happen (if you can tell them right, that’s a big if), and, should someone have received notions about the place, and the work challenges those notions, well, good. Once I had a character listening to a certain song, and someone said no young mid-westerner would be listening to that song, and I thought 1) how could you possibly know that? and 2) you seem to be criticizing the work for questioning your generalizations. But I think that’s what fiction should do.

[How to write about a country that is so fixed upon what's happening day by day (news, celebrities, national and international disasters, etc., etc.) while making it timeless?] I guess I don’t write about that country. Objects and images I have remembered over a long time are most useful to me—if they’ve lasted in my memory, they’re important for some reason. That leaves out much of what is new and day-to-day. When a book is advertised as revealing how we live now, I think, I am living now, tell me something else. Also, a lot of the reading I do is of mythology or folktales from centuries ago, and that influence may be evident.

Yan: [In place of realism and magic realism?] I have come up with this term: divine realism, which I hope may work for our Chinese reality. In divine realism, there is not a reason, or not any logic, but things just are, and are accepted. For instance, the stories of Liaozhai—I used to listen to the elders retell those ghost stories when I was little—we never question that a fox could turn into a beautiful woman. Why? Because we’ve accepted that foxes are sly animals, and they come out to seduce bachelors. And much of our folk tales and fables I would call divine realism. And the pigs in Huangpu River? We don’t have to ask for the reason why they are there: we accept that money and desire and corruption are involved. That inner logics, even though they don’t look logical on the surface, are already in place before the story starts.

Drury: I found a selection of the Liaozhai stories at a used-book store in Providence, in a 1946 English edition called Chinese Ghost & Love Stories, translated by Rose Quong, an actress and lecturer from Australia who lived in New York from 1940 on. The book has a striking red and black cover and it's one of those books you imagine you're supposed to have found. I just fell in love with the stories and woodcuts. Foxes are spirits, ghosts and humans fall in love, a soul can leave its body and land in another one, and all told in a credible, matter-of-fact way. I wanted the world to be that way, to have that kind of pantheism, and occasionally it seems like it does.

I like it when the inner logics of a story (normal or paranormal) are mysterious but convincing—as Yan suggests, taken for granted by the teller of the tale and its audience. And I think the reason they are taken for granted is because they originate in something anyone can understand. In the cases of foxes that turn into beautiful women and seduce bachelors or lonely scholars, you don’t have to look very far to see the human desire behind such a story, especially if it’s written by a bachelor or lonely scholar. Spirit stories, similarly, reflect the common desire for life after death, for “happily ever after.” Yet there’s often a danger for the mortals in these stories, which expresses a wariness of hubris, of crossing fixed boundaries. Last year I read a wonderful novel by Kira Henehan called Orion You Came and You Took All My Marbles. The protagonist is a woman called Finley and she is given strange assignments in an unreal place, a sort of transitional world if I’m reading it right, and the story feels absolutely credible as an imagined scenario originating in a trauma that is hinted at but never named. Finley carries out, or fails to carry out, her assignments with a lot of humor and spirit, which not only makes the story irresistibly readable but demonstrates the need to go on in a world of trouble and uncertainty.

Brokenness

Yan: When I was fifteen, sixteen, for a year or two I was writing without knowing what I was doing. I wrote this whole novel, a thick stack of paper, which my mother, who did not read, fed the stove. She might as well. The only thing I knew then was that a novel should be a hopeful thing, like A Bright Sunny Day or The Golden Road [two of the most famous revolutionary novels in the ’70s—YL].

Later—after I worked up in the army as a slogan writer, a librarian, a journalist—I had a bad case of dislocated discs, and for two years was not allowed to move. When you were bed-bound for so long, even as a man you couldn’t stop weeping at times; only then did I start to read real literature: Kafka, Garcia Marquez, Faulkner, and Borges. It’s interesting how illness opens up a mind.

Drury: [Regarding his essay on literature starting with brokenness: But what happens before brokenness—or does it not matter?] The unbroken thing has promise. You know, Lear’s kingdom, how swell it would be to have that. (Then it gets split up, and there’s mayhem.) Or you buy something at the store with all kinds of expectations of how cool your life will be with this thing. Or you’ve had something for a long time and it seems to represent the continuity of how you’re living. It all may be an illusion but minds work that way. I started Pacific with the idea of an old table spontaneously falling apart in someone’s house. I think I’ve seen that happen, and it seemed a good way to begin a story of dislocation and change. Also, it’s interesting. Why would something up and break on its own? The molecules have reached a certain point where, what, they give up, I guess. This is the pathetic fallacy in action, but I like to think that the broken thing wants to be whole, and the attraction of the broken pieces to one another becomes a force that drives the story.

Back to Top

Author

Yiyun Li is the author of seven books, including Where Reasons End, the winner of the PEN/Jean Stein Award; and the novel Must I Go, which will be published by Random House in July. She is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Guggenheim Fellowship, and Windham-Campbell Prize, among other honors. A contributing editor to A Public Space, she teaches at Princeton University.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

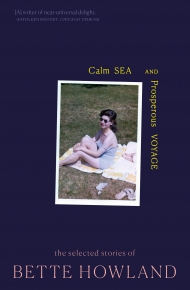

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.