On Translating Du Fu

• Aaron Crippen • November 4, 2013

For a poet, there must be no greater pleasure than reading classical Chinese. For a translator, there may be no greater challenge than translating it. For Chinese writing is unique, with its pictographic roots. Fundamentally, its words do not denote sounds, as in alphabetic languages, but objects—such as 日, the sun—or combinations of objects to express ideas—such as 明, the sun and crescent moon together, meaning “bright” or “clear.” Its curves have been straightened and standardized, but in 日 we still recognize what was once a circle, like the sun, with a dot at its center.

And in 日 we see that Chinese words can contain space, not only the image of the sun, but the distance from our eyes to it. In 山, “mountain,” we see not only the three peaks of a mountain ridge, but the distance to that ridge when it seems that size. So 山 is almost panoramic. No Imagist could ever hope to achieve what Chinese does in a single-syllable word such as 旦, meaning “dawn”: the sun seen above the line of the horizon, the distance from one’s eye to the horizon, the greater distance to the sun beyond the horizon, the time of day when the sun is there, even the color of the sun at that time.

Ask a group in English to picture “dawn” and each person will picture something different. (This is how Sartre was dazzled by the idea that words do not point to things.) Ask a group in Chinese to picture 旦 and the effect is quite different.

Thus an old Chinese poem of forty syllables, such as “Spring Scene” by Du Fu (712-770), is capable of picturing many vast spaces, luridly colored, incomparably concrete. And the old Chinese poet is like a god, setting pieces of creation side by side like great stones, but with more precision, like a bricklayer, whose bricks are square solid glass with scenes inside.

Since its words are rooted in pictures of things, Chinese is inherently materialist: it cannot lift off from this world to a place where trees and suns and eyes do not exist, into the abstract realm of God. To achieve the ineffable Chinese writers rely on mystery and paradox, like Laozi (Lao Tzu), or absurdity, like Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu). In poetic terms, Chinese is utterly concrete; it resists abstraction. In Du Fu’s forty-word poem there are nineteen nouns, ten verbs, five adjectives, four adverbs, two numbers: no articles, no prepositions, no conjunctions.

Once a Chinese student said to me “We Chinese believe that every word is like a drop of gold.” This is the challenge to the translator of classical Chinese: to find words with the density of metal, the coloration of gold or of the sun, the concreteness to bear the weight of a poem in several syllables. And there is the need to convey the complexity of the whole poem.

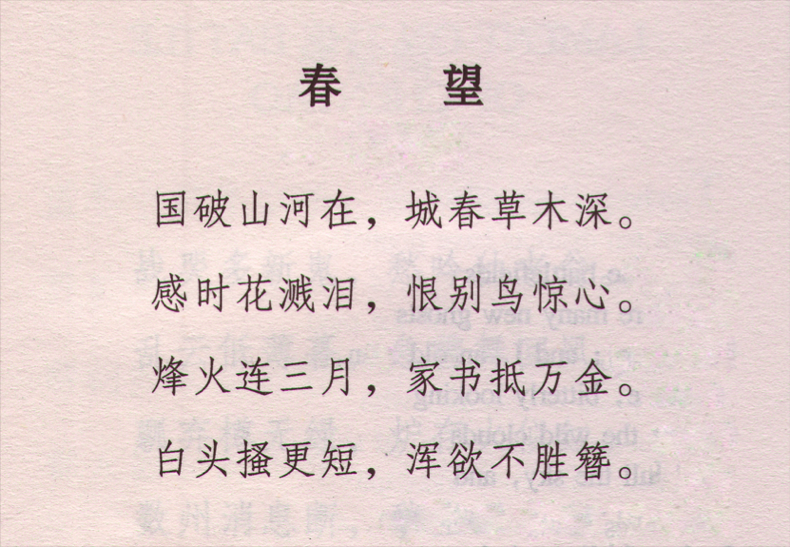

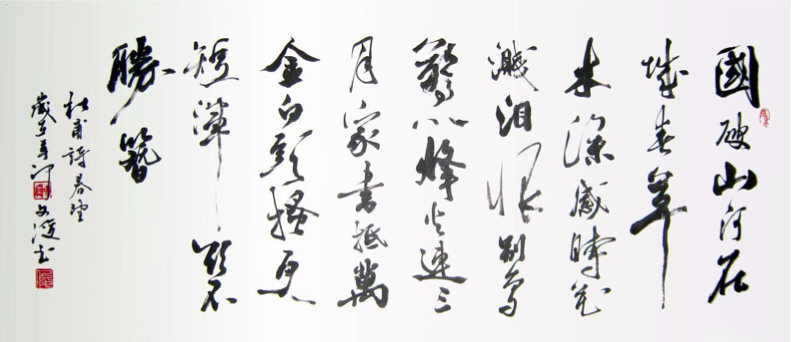

Below is the forty-syllable, forty-word poem of Du Fu I have translated from the “simplified” Chinese of the P.R.C. Following it is a calligraphic version much more like the one Du Fu must have written in traditional Chinese, before the first wood-block book was printed. For convenience’s sake, I’ll call it “the original,” although it is only a stand-in.

“The original” is read top to bottom, right to left, while the simplified is read in the same way we read English. “The original” has no punctuation or lineation: as with prose, each calligrapher may end his line at a different place. “The original” in this case gives special emphasis—I don’t know why—to the word for “grass,” which is long like a dagger in the second line from right, and, situated at ten o’clock from it, to the word for “hatred” (of separation from loved ones).

Some words that are supposed to denote the same thing are written differently in traditional and “simplified” Chinese. For example the first word of the poem, meaning “state” or “country,” in traditional Chinese is the image of a weapon like a halberd beside a walled town, all of which is surrounded by a rectangular wall (國). This version of the word fits very well with the content of the poem. On the other hand, the “simplified” word for “state” or “country” is an image meaning “jade” surrounded by a wall.

Because Chinese words do not necessarily specify sounds (which is why users of the same writing can speak mutually unintelligible dialects), it is capable of visual rhymes and repetitions that are not heard by the ear. For example in the second line of the typeset poem, the last word, meaning “heart,” can also be seen at the bottom of the first word in the line. A modified version of this “heart” can be seen on the left sides of the sixth and ninth words in the line. So four “hearts” appear in the space of ten words and the eye, not the ear, picks this up. It is a very emotional line.

There are also aural rhymes in the poem, as we have in English. This poem is in the form of a lushi. The typeset poem derives its lineation and heavy punctuation from this form. It is hard to know what was a straight rhyme and what was a slant rhyme in Du Fu’s time, thirteen hundred years ago. But we know that the rhyme scheme at the end of these four lines must be AAAA. With these four A’s we may find up to fifteen more words that slant rhyme in the poem.

In translating “Spring Scene,” I sought first to preserve the brevity and concreteness of the original, opting often for monosyllabic words. I am a great fan of Allen Grossman’s Summa Lyrica. I agree with him that a short line is a short expiration in the greater silence, like a brief life, even in Chinese; and this poem is really eight short lines, not four longer ones. I despaired of replicating the dense rolling rhyme of Du Fu’s original, only hoped to give a sense of it. To convey the highly formal nature of the poem, I chose an iambic framework.

It is my purpose as translator to be as transparent as possible, while I know that my mind will inevitably color the poem. One way I try to achieve this transparency is by translating linearly wherever I can, preserving the word order of the original. (If I reorder the words of each poet I translate, then each poet will end up sounding like me.) Also I know that, just as two paintings have different effects when they are hung to the left or right of each other, two images have different effects depending on the order in which you read them.

Finally I should note that most Chinese words do, in fact, give some indication of how to pronounce them. For example the existence of 北 in 背 lets you know that the latter must be pronounced similarly to the former. But the question remains as to how you must pronounce the former, and there is no indication of that.

Back to Top

Author

Aaron Crippen is a poet and translator whose awards include a National Endowment for the Arts Translation Fellowship and the PEN Texas Literary Award for Poetry. He translated and edited Nameless Flowers: Selected Poems of Gu Cheng and was a primary translator of《当代美国诗选》(Modern American Poems [People’s Literary Press, Beijing: 2011]).

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.