There Will Never Be Another Person Like Jim Again

News • Yiyun Li • August 12, 2016

The first year I taught freshman rhetoric at Iowa, a young woman announced at the beginning of the semester that she was from a Catholic, white supremacist background. She wrote in her weekly report—read only by me—that anyone who is not white or who is not Catholic will go to hell.

I had been in America for six years then, but my immigration status was nonresident alien. I had not met a white supremacist before. She always sat in the center of the semicircle, so she and I, face to face, could never escape each other. At the beginning of every class I reminded her to put away her Daily Iowan, which covered her text book and expanded into her neighbor’s space. Sighing heavily, she would fold the paper slowly. All students would watch her. I would make a point of waiting until she put away the newspaper before I started teaching.

Would you like me to take her out of your class, my advisor asked. Transferred so she could be taught by a white teacher? I thought; that would be a defeat I could not stand. No, I said.

The truth was, the student baffled me. When other students showed the slightest sign of distraction and talked among themselves, she would hiss at them. Hey, be quiet, she would say. She’s talking. Listen to her.

She intimidated me, too. She intimidated other students in my class, including a Japanese American from North Carolina, an Indian immigrant from London, a native Hawaiian who had set foot in the mainland US for the first time that fall, and a Guatemalan American from Illinois. The last one, who liked to stay after class and chat, said to me one day about her white supremacist classmate: Can you believe that we have to see that girl four days a week?

We must believe a girl like her exists in our world, I said. Though I wasn’t in a better place, as I too asked myself the question: Can you believe you have to battle her with her newspaper four times a week for the rest of the semester?

I went to talk with Jim. What I told him didn’t surprise him. My experience was only a small fraction of what he had lived through for decades. He said that it was a good decision to keep the young woman in my class. Her upbringing, he explained, makes it imperative that she submit, without questioning, to all those who have authority over her. That’s why she would not allow other students to show disrespect to you, he said. Her upbringing also forbids her to treat you as a fellow human being, and that is why she has to show her defiance. Every day you walk into that classroom you make her feel an irreconcilable conflict, you see that? That’s a good thing. You’re the beginning of her education. Jim then went on to tell a story from his own teaching career when he had first arrived at Iowa: a young man who had not welcomed Jim as a professor came to him years later with respect and friendship. She may change, or she may not, Jim said of my student. But we must hope she will.

I’ve often thought of myself as a more pessimistic person than Jim. The world is not becoming any better. Still, there is a way to exist in this unfriendly, even alien, world and make a meaningful difference. It is to write, it is to teach, but it is also to insist on standing where we are, being who we are, so that those who do not want to experience conflicts are made to confront what they don’t care to see. One does not have to be loud or angry or confrontational. One only needs to be stubborn, persistent, dignified, and yet able to recognize the limit of these efforts.

This is a conversation among many I had with Jim, and this is one of the many things I’ve learned from him. I wish I had time to recount all of them. But this must be what all his students feel.

I met Jim fifteen years ago. I signed up for his summer workshop, which was open to the public. I really did not know what I was doing in that class. I had only written fragments and had not yet completed a story. My English made me shy among my peers and nervous around Jim. I was seven months pregnant and miserable in the heat; I was a good scientist but my status in this country would remain nonresident alien for a long time.

Jim was soft spoken, and I did not understand him much. But one day he talked about Western individualism and Japanese culture, about a communal voice lost in contemporary American literature but still present in Eastern culture. That day I understood him—perhaps only two or three sentences—and I went home and wrote my first story, told in a communal voice.

During the workshop Jim talked about the audacious movements in the story. I was at a loss. I had not known I made any move. Afterward, I explained to him that I had never written anything, but I wanted to be a writer some day.

He looked at me with that look easily recognized by those close to him, a look of surprise and mischief and bashfulness. You want to be a writer? he said, but you are a writer. I can’t teach you anything.

You are a writer—that was what Jim repeatedly told me in the following year. He was on sabbatical, but he wrote often, asking about the newborn baby, telling me to seek out Marilynne Robinson and Sam Chang—before he left town he had told them to welcome me to their classes. Keep writing, he always said in the letter; you are a writer.

If Jim said so, it must be true then. What Jim saw in me made me the writer I am today. But this is only one student’s story. I’m only one of hundreds, one from a generation of writers he helped and nurtured and believed in.

In 2015, I came back to teach at the Workshop for a few weeks. The Sunday I landed in Iowa City—Easter Sunday—I met Jim and his old friends, David and Rebecca, for brunch. Afterward I took Jim out for a drive in the countryside. Beautiful landscape, he said, pointing out bridges and creeks and the streets that abruptly end, with open fields spreading beyond under a gray sky. Beautiful landscape, he said when we drove from one town to the next, reminiscing about his first arrival in the Midwest. I noticed a house with a handwritten sign, “He Has Risen,” on a piece of cardboard in the front lawn. I parked the car and told Jim I wanted to take a picture of that sign. It’s a beautiful and strange world. Iowa had become his home. Any time I return to Iowa I still call it a homecoming.

On that Sunday we also took a selfie together. Jim had the same look of mischief and wonderment and bashfulness in his eyes, and how I love that look in his eyes. It was the same look when I told him there would be a baby named after him; when my friend and I told him, meeting at Bruegger’s Bagels, that he was not allowed to feed the meter (an excuse he used for a cigarette break). He did it in any case, standing outside the window and waving a cigarette to draw our attention. He must have had the same look when, once, I called him from California and said if he didn’t eat well I would call him three times a day. I’ll eat the telephone first, he said; the next time I called, he said, I’ve eaten the telephone.

The last day I was in Iowa, in 2015, I went to see Jim. There were lunches and a visit to his house we had planned, but time, as always, is less generous when we need to spend it with a beloved one. Oh, you’re leaving so soon, he said. Look, I was hoping we could go out to lunch; I put clean clothes on, he said.

I cried then. I cried again when the news of Jim’s passing reached me in California. But tears, like words, are inadequate.

James, who met Jim when he was a newborn, grew up knowing Jim by pictures I showed him and by tales. One of James’s favorite books is Charlotte’s Web, and he memorized many lines from that book.

I thought I would borrow James’s favorite line from the book to end this: “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.”

With inadequacy, I will rewrite that line as this:

It is not often that someone comes along with inviolable independence and unsurpassable kindness; who knows when to laugh and cry, with whom to laugh and cry; who is a true friend and an inimitable writer, a giant among us. There will never be another person like Jim again.

Back to Top

Author

Yiyun Li is the author of seven books, including Where Reasons End, the winner of the PEN/Jean Stein Award; and the novel Must I Go, which will be published by Random House in July. She is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Guggenheim Fellowship, and Windham-Campbell Prize, among other honors. A contributing editor to A Public Space, she teaches at Princeton University.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

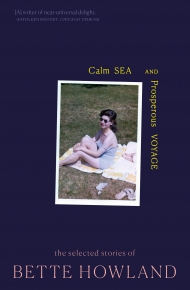

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.