On “A Lucky Man” by Jamel Brinkley

• Victor LaValle • July 15, 2016

There’s a particularly moving scene in There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film about an oil tycoon, Daniel Plainview, running around the American West acting like a maniac. His antagonist is a religious man, Eli Sunday, a young preacher and faith healer. The two spar throughout the movie. At one point Plainview attends a church service led by Eli. Sunday has extorted Plainview into coming so there’s a great deal of tension between the pair when Eli calls Plainview up to the pulpit to confess his sins. Plainview is clearly barely tolerating the theater of the moment but Eli is in his element, electrified, as the members of his flock watch.

“We have a sinner with us here who wishes for salvation,” Eli tells the congregation. “Daniel, are you a sinner?”

“Yes.” This answer comes quickly, something perfunctory.

“Oh, the Lord can’t hear you Daniel. Say it to him, go ahead and speak to Him. It’s alright.”

“Yes.”

“Down on your knees. Speak to him. Good. Look to the sky and say it.”

“What do you want me to say?” Daniel asks, sounding snide.

From here Eli Sunday goes on to list Plainview’s indiscretions: lusting after women and abandoning his child. It’s the latter that finally strikes a true blow at Plainview, his face going tight with anger and shame. Eli demands that Plainview say he’s a sinner; that he’s sorry to the Lord; that he wants the blood of Jesus. Plainview offers all of this. But Eli returns to Plainview’s sore spot.

“You have abandoned your child.”

Eli demands that Plainview admit this, out loud, before all. He pushes him to say it once, twice. Finally Plainview cracks and shouts, his throat red from the confession.

“I’ve abandoned my child! I’ve abandoned my child! I’ve abandoned my boy.”

Right after this, there’s a moment where Plainview bites his lip and looks away and you can see the character, and the actor—Daniel Day Lewis—truly contemplating the horror of this, his greatest sin. For that moment, Daniel Plainview is neither mythic hero nor epic villain, but simply a human being forced to truly reckon with his commonplace monstrousness. He’s turned out to be a disappointing father and, at least for this moment, he knows it and can’t hide from the truth. It’s the truest emotional moment in the movie.

I tell you this longish anecdote as a way to prepare you for what I see as the magic in Jamel Brinkley’s stories. These stories deal in large-scale deceit and betrayal, there are painful things at work in this fiction, but much like the scene I described above, Jamel Brinkley regularly finds ways to pierce through the dramatic and find the subtle and humane lurking within.

He’s got a way with language, that’s always a good start. Here’s a paragraph, picked nearly at random, from his story “A Lucky Man”: “Something feverish coursed through the avenues of the city that morning. After weeks of disappointing weather, it was finally and fully spring. Rain clouds had been wrung away, leaving a clarity of unbroken sky and a sheen on everyone’s limbs.” A fine way to write a lovely morning in New York City but fine language, without deeper meaning and intent, is just costume jewelry. When you read the whole story, you glean the ways Brinkley is seeding something essential about the protagonist, an older man named Lincoln, into the way he’s seeing the city and its residents. There’s a tone of appreciation and pleasure, but maybe also hints of appropriation and lust. And all of that comes to mean a great deal by the time you read the painful, but earned, last line of the whole thing. This is the kind of fine-motor-skill writing that impresses even more when you read the story for a second time, a third.

There’s another reason I began this note with a description of the scene from There Will Be Blood. Brinkley is writing with great insight and honesty about men who are much like Plainview, by which I mean men (and women) much like all of us, who can’t see ourselves clearly, who overlook our failings and overpraise our virtues. In these stories he’s both Eli Sunday and Daniel Plainview; he’s the congregation and the film’s director, too. He approaches the story from all of these angles so you and I, the readers, his audience, might sit just far enough out of frame to understand that by bringing all of this together, by using all his formidable talents, he’s shown us a vision of ourselves.

Read Jamel Brinkley's "A Lucky Man," originally published in APS 22

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

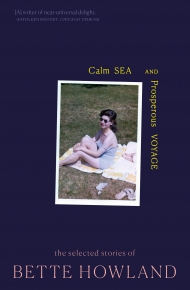

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.