“The Let-Out” by Jamel Brinkley

28.5 • May 27, 2020

"It might be true that discomfort is one of my own primary modes of experience. So much of living has been about discomfort for me. Maybe discomfort is related to vulnerability and sensitivity, and maybe for me it’s one of the most effective ways by which a person or character can... have their settled notions of themselves pierced to open up a space (a wound?) for self-reflection. I’m deeply suspicious of the idea that people or characters can suddenly undergo deep and genuine change, or that radical change and true epiphanies are common, but I am completely faithful to the idea that there are moments when we can be profoundly shaken." —Jamel Brinkley, in conversation with Brandon Taylor at Lit Hub.

"The Let-Out" is a story of one such moment. It appeared in A Public Space No. 28, Jamel Brinkley's third story for the magazine. (His debut story, "Infinite Happiness," appeared in A Public Space No. 21.)

Jamel Brinkley is the author of the story collection A Lucky Man (A Public Space/Graywolf), which was a finalist for the National Book Award, the Story Prize, the John Leonard Prize, and the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize; and the winner of the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence. He lives in California, where he is a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

***

The woman came out of the museum and navigated the masses in the plaza. She fluidly pivoted left and right, and no matter which way she moved, or how often men tried to get her attention, her gaze remained soft, placid, nonchalant as she surveyed the crowd. Every first Saturday, the museum offered free admission as well as lectures, performances, films, and a dance party, a popular program of events attended by thousands of people. Aside from the leering Romeos and the expected head turners, there were also white people and elderly people, families burdened by their kids. The woman cut through them all with unperturbed elegance, or they moved their bodies to make way for hers, or it seemed like they did. The gold and emerald colors she wore leapt out, the lit glass of the museum’s pavilion glowing behind her. One guy stepped away from his friends and into her path, but she dodged him effortlessly, the hem of her floral sundress fluttering, her purse bouncing against her thigh. He reached for her wrist, but with no effort at all her arm slipped away, escaping that too, and he turned to watch as a breeze pulled her dress against the shape of her body. The woman’s mellow beauty—and her tranquil, charming rejection—left his eyes full of bitter longing. Then her gaze abruptly sharpened. Whatever she had caught sight of caused her to halt, and her expression became puzzled. She shook her head, the movement like a tremor had run through her, as though a notion had charged into her mind only, seconds later, to collapse under the weight of uncertainty. But all of a sudden she started walking again, with more quickness and purpose. Her steps were bringing her in the direction she was looking, and it became clear, despite every self-abnegating doubt, that she was walking toward me.

Read on.Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

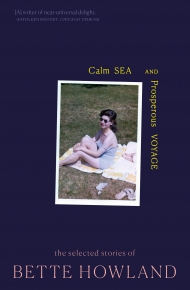

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.