Witches’ Rings

• Kerstin Ekman | Selected and Introduced by Dorthe Nors • May 2, 2014

The snow melted, exposing the dead body of a man on a hillside just behind Tubby Kalle’s tavern. There was a narrow alley between Tubby Kalle’s long privy and the next building, where a yard hand lived. People called it Old Man's Alley. At the bottom of the alley was a little slope used by the three or four nearest houses as a rubbish dump. That's where he lay. The sockets of his eyes were sticky, his black coat was spotted with snow mold. The frightening thing was that no one knew who he was.

It had come to that. A man could get off the train for some unknown reason, stop in at the bar-room at the inn, go from there to the nearest tavern, and end up at the last outpost, Tubby Kalle's. Get himself drunk and shown the door. Perhaps take a few reeling steps and, finally, slide down the slope and not be able to get up again. There he lay still, with his feet in a set of bed springs Kalle had tossed out last autumn. He might have frozen to death. Perhaps something else had happened. Doctor Didriksson would settle the question.

The Doctor and Pastor Borgström from Backe shared a trap to the village. It was Annunciation Day, the trap shook and rattled along the rutted track, and the mud stuck to the wheels. The two officials sat leaning in opposite directions, in dull resigntion. Inertia and Acedia were in harness.

I detest spring, the doctor was thinking. “That’s when the corpses show up. Excrement flows like rivers. I hate spring, early spring. The time of death and denigration. It’s ages before things start to grow again. They say that autumn is when things decompose, but that's wrong. Autumn brings frost, before which the earthworms have skillfully pulled the leaves into the ground. There’s nothing but the rough earth, with its thin matted blanket of hibernating flora and fauna. The smell of spices. The doctor tried to recollect this to brace himself for the task at hand.

The body had been home across the station yard on a door, across the tracks and the market square, up the hill to the Agricultural Guild barn, where the cattle were kept on market days until they were sold or awarded prizes. Farmer Magnusson had built the barn for the Guild. He still owned it. It was the only truly public facility in the village that was not in the station yard. The pastor was going to hold a service in the barn loft, where a table had been covered with a white linen cloth with lace insets, a gift to the community from the wife of the former stationmaster. Borgström had some church candlesticks and a couple of candles with him in a black bag. Women dressed in black were already at hand and ready to arrange the silver.

They had swept the floor and straightened the chairs into rows. A chartreuse painting of a gently smiling Savior hung between the two windows. Still, nothing could disguise the scents of tobacco and sweet powder that permeated the air. The windows wouldn't open—they were rotten and jammed shut. The parson, plagued, moved into the back room, where whist players, lecturers and rustic comedians drank beer and changed clothes before performing. Normally he sent his assistant to hold services in this godforsaken place, but unfortunate extenuating circumstances had compelled him to come along personally, and he was now so distressed that he was perspiring in the damp heavy wool of his cassock.

It was ten o’clock. At the inn, Ozman Cantor and his assistants, who had held a magic show here the night before, were still asleep. Cantor, whose accent was a combination of German and an equally foreign Swedish dialect, had been very close to taking a beating during the performance, which was too miserable to satisfy even the low expectations of this community. In order to wring a little extra money out of his audience, he had brought with him a pig to raffle off. Most traveling entertainers had a raffle, but Cantor never dared to show his audience the pig, and that was probably wise. Magnusson himself, concerned that people might be smoking in the loft despite his prohibition, had gone up personally to have a look. He had watched the magician sweat for a while, watched his heavy, bruised assistants move suggestively so the powder flew hot and sweet off their bare arms.

“Those folks can't do no magic, except possibly with their bums,” he let slip, and this was enough to trigger some sniggers in the mounting atmosphere of dissatisfaction. Thus Magnusson saved Ozman Cantor from the violence that was brewing.

His assistants had spent the entire night performing the only magic tricks they knew for members of the audience, after which they had slept like the dead, still smelling of powder, and now one of them awoke, tormented by an incredible thirst. When she went out to find some water, she bumped into Edla, carrying a heavy basket. As usual when she went out, she was wearing the shawl Hanna had given her, with the ends crossed over her stomach and tied behind her back. They stared at one another for a moment before Edla walked out the door to cross the station yard in her leaking boots. She wouldn't wear her new ones in the spring mud.

Doctor Didriksson had poked unenthusiastically about in the corpse of the man in the Agricultural Guild barn and then, beside himself with disgust and nausea, turned it over to the barber surgeon and the vaccinator to continue if they pleased. Didriksson’s predecessor as provincial physician had mostly served the estate, the manors, the captain's lodgings and the parsonages. His specialties had been gastric disturbances and migraine attacks. Didriksson had despised the old doctor for his dinner invitations and card-playing evenings, and had taken up his post two years earlier with entirely different ambitions.

Soon enough, however, the railway hamlet took the sting out of his desire to serve a wider circle of humanity than hysterical parsons’ wives. It seemed to him that the railway carried around all the claptrap and refuse that sifted down to the bottom of a society. They fell ill in the waiting rooms and then, with any luck, died in the overnight rooms of the inn. His mission of saving lives seemed to him more and more questionable. There was nowhere to put lives that could no longer he carted around by the national railway company. At the provincial hospital half of the patients were already people suffering from venereal disease.

He did not know, and never would, who the man found on the slope behind Tubby Kalle’s had been. He was indifferent to the cause of death, but his guess was intoxication and exposure. He walked up the already extremely well-worn staircase in Magnusson’s sloppily built structure, found the pat-son and sat down with him in the little room where magicians put on their costumes and where the clerical alb and stole were now lying across two chairs.

“This village needs a policeman,” Didriksson said.

“True, true,” said the parson, feeling tired at the very thought of all the social issues this corpse raised. One of them was the question of where to bury him. It would not do to bury an unidentified person in the Backe graveyard, the farmers wouldn't have it. This one could be shipped to Nyköping on the pretext that the provincial physician would have the resources to carry out a more informative autopsy, and hopefully they wouldn’t return it.

Someone knocked on the door, as softly as if a bird had tapped it with its claw, and the pastor called, “Come in.” Edla opened the door and stood there, with a runny nose and carrying a hamper.

“I've brought the parson's meal,” she said, and both dignitaries stared at her. The pastor had no idea that his assistant had an arrangement with the inn. When he arrived cold and stiff on Sunday mornings in a far less pretentious cart than the one the pastor had hired, he began by having a little breakfast sent from the inn. Either Edla or Valfrid brought it up to the Guild loft in a hamper. He would have a flask of oatmeal gruel stuffed into a stocking to keep it warm. The prunes floating in the gruel tended to get stuck in the neck of the flask. Fru lsaksson had put cold pork, sausage, eggs, and cubes of smoked ham between slices of dark bread. The doctor and the pastor poked around in the hamper, laughing at the idea of the pastor's assistant sitting here every week, freezing in front of the little stove, eating all by himself. It was about as simple and coarse a breakfast as one could imagine, and they had no intention of eating any of it. But somehow the pastor broke off a piece of rye bread, and then began to eat the smoked ham, one cube at a time. The doctor lit his pipe, and the pastor sneezed loudly from the dust and the grains of powder floating in a ray of sun from the window of the loft.

That sneeze was a release. The pastor perked up more than he had in years. He felt as if he had been transported back to his student garret in Uppsala, and the doctor with his puffing pipe full of tobacco served to reinforce the illusion. The two gentlemen began to discuss religion, a subject the pastor hadn’t debated in thirty years. The doctor found himself getting caught up in the spirit. He grew sarcastic and ironic, and was excessively and youthfully blasphemous as he tried to put theology in its place. In fact, he was suddenly more youthful than he had ever been in Uppsala. They spoke of the text for Annunciation Day, the most sensitive theological issue of them all.

“Tell me now, brother, what you intend to say to the wives of the stationmaster and the postmaster today—not to mention the wife of the yard master—on the subject of the Jewish girl of thirteen or fourteen in Nazareth, and of her fate.”

“Don't call it fate! We must recall that she had a choice,” said the parson, enlivened by the acrid tone of voice of the physician. “She embraced the angel's message. We must recall that the Holy Spirit gave Mary a choice, he wasn't commanding her. My sermon will be based on the idea that God gives mankind a choice, and it is up to man to decide whether to respond in the affirmative. That's the Gospel. That’s the miracle. Compulsion and commandments were the attributes of Judaism.”

“A nice thought,” said the doctor. “But I’m sure, brother, you know just as well as I do that when Mary says yes, her answer is merely pro forma. Our lives are regulated by laws. If nature doesn't get her way, she resorts to coercion.”

Edla sat by the door waiting for the hamper, which the gentlemen absentmindedly emptied of everything but the gruel. She had no idea what they were talking about. They called the Virgin Mary a Jewish girl of thirteen or fourteen. Was Jesus’ mother the daughter of a Jew-peddler who sold clocks and old clothing at market? She didn’t understand, didn't want to understand.

The doctor’s eyes met Edla’s. His gaze happened to fall on the girl by the door and for a few seconds they looked one another in the eye. He was startled and disturbed by what he saw, but he quickly put it out of his mind. At that age, children change so fast. He was caught in a hiatus between the theological discussion, with its tobacco smoke and its intoxicating freedom, and this Sunday in early spring with its mess of slushy snow. Out of sheer politeness he would have to sit through Borgström’s sermon in the loft of the cattle barn of the Agricultural Guild.

He suddenly knew he would never make it through the sermon. He no longer cared what the parson thought, but rose and made his apologies. On his way down the rickety staircase he met the barber surgeon and the vaccinator, who were extremely upset. While examining the corpse they had pried open the man's jaws and had a look inside. The deceased had a communion wafer in his mouth.

That was the Sunday Edla got home to Appleton frozen through and with soaked feet after a dreary pilgrimage through the melting snow. Her eyes were black and glistened with fever, and Sara Sabina looked at her over her shoulder several times as she was making the fire. Nothing was said, however, mostly because the soldier was sitting in his seat by the window, holding forth. He went on about how his ability to formulate a letter had led to that wonderful domestic position for Edla.

I wish you’d shut up, the old woman thought, but she didn’t say that, either. When it came right down to it, she did not think it was good for a daughter to hear a mother shout at the king of creation.

One of the ewes was in labor, and Edla went out to the sheep shed to see if her time had come. When she didn't return, they thought she had left for the inn without further ado. Edla never made a fuss. But the young girl had, in fact, climbed into the ewe’s pen and laid two burlap bags over the straw. The ewe was all the way over in the other corner, head down, staring at her. Edla had decided to stay and see how it happened.

When Edla decided to do something, she took it seriously. She had long ago learned to ward off fear by making one little decision after another, and by implementing them promptly and uncompromisingly. She often impressed Valfrid, who tended to be frazzled and to run around mindlessly, fretting about what might go wrong. When he was worried, he could easily set the storehouse on fire, or cut off his thumb, or drop the key to the innkeeper’s desk into the treacle barrel.

Still, the lengthiness of the ewe’s labor was wearing away at Edla’s grave concentration. The abdomen was distended and the udder was tense and hard. Edla was sure she had been sitting there for at least an hour, but nothing was happening. Against her will, and against her every intention, fear began to prickle her skin. The ewe was in pain. Something was wrong. It was as if Valfrid were sitting beside her, whispering and egging her on. “Can't you see something’s gone wrong?” She must have seen animals give birth before, but she hadn't paid attention to the details. There was one thing she knew: it didn’t usually take so long.

Hours must have passed, and the ewe was still standing there patiently bearing her pain. Edla could hear the cows silently chewing their cud on the other side of the wall. If she looked up at the opening, the daylight coming through the crack blinded her. The spring sun was baking the outside walls of the sheep shed, waking the nettles and insects to life.

Did the ewe know or not? Could she remember? And if this was her first time, how could she be so patient? As if she already understood: this was the pain l was born for. It’s no use fighting. She rolled with the waves of pain, pulling her head back, shutting her eyes. She let the pain rule her, without asking what good it would do.

The hours passed. The udder was shiny and ready to burst, the teats were swollen and their color shifted from rose to purple. She stamped, scraped her front hooves, walked round and round in the bed of straw, and lay down heavily. Now her belly was part of her again. Earlier, it had hung far below her, looking as if it didn’t belong to the same body as her sharp backbone. She pulled back her upper lip as the ram had done when he mounted her, except that hers was drawn back in pain. Edla did not expect her to stand up again. She was so heavy and the contractions were so strong that she would not be able to stand again until it was over.

Yet there she was, on her legs again. She stood still for a long time scraping one hoof, holding her head stiffly to one side. Her back arched in pain. A violent contraction hit, and she bowed her head submissively, her big, dark eyes no longer seeing Edla or anything in the world around her. Her gaze was rigid, shadowed by her white eyelashes.

Her haunches seemed to grow heavier and heavier. Time and again she drew back her lip. Once, a ball of cud came up, but she swallowed it down without chewing. Then she dropped. Sounds began to come out of her, she moaned softly and regularly, her ears pulled back. Her gaze was dull and much lighter now, her pupils contracted to slits.

Edla leaned her head against the timbered wall. She was extremely drowsy, at the same time as she was inexplicably frightened. The next time she looked, the ewe was standing again, standing perfectly still with her head extended. This is going to go on forever, Edla thought, dimly fearful. Time and again she fell, her belly heavy, and each time it was increasingly difficult for her to stand up again. Dear, sweet Lord, why does it have to be this way? Poor creature. The ewe gasped in pain, silently opening her jaws wide. There was stretching and creaking, but she did not voice her agony.

The country mice were having a heyday around the drowsy Edla. They ran close past her feet and played in the straw she had spread out. The tail of the ewe stood straight out. Edla stared, only half awake, at the opening of her genitals. It was pale red and runny, and its folds and creases were in motion. She felt as if she had been staring at the hole for hours. The ewe gasped in pain, opened her jaws painfully wide and moaned. She was lying on her side, working, her legs stretched out straight. Her stomach rumbled, vibrating with air between the contractions. But why in the name of God was it taking so long? Suddenly she saw a bright red bubble protruding from the hole. The ewe rose and bore down. Inside a tough membrane sac the color of deep saffron, lay the lamb, legs curled, apparently lifeless. At that moment, Edla, sick with dread, realized what a stillbirth was.

She had barely begun to take it in when the ewe turned around and poked at the sac with her muzzle, uttering a three-syllable sound Edla had never heard before, a soft, safe sound. The newborn lamb kicked. It was alive. Edla wept with queasiness and joy and exhaustion. A second kick—but it looked as if the lamb would suffocate. No, the ewe began to lick the thick yellow membrane off its baby's head, constantly uttering those soft three-syllable sounds, chuckling. The lamb responded the moment its head was free, with a soft little scream, and then it wobbled blindly towards the udder, still half covered with the thick yellow fetal sac.

No, that was not what l thought it would be like, thought Edla, as she climbed out of the stall, her stiff legs all pins and needles. “Not a bit. Very, very different.” She had learned something. Out in the sunshine, she tried to sneak past the house and make her way down to the road without being seen from the window. She had learned. A woman who was giving birth must not rebel. She must work patiently, for pain is a strict taskmaster. See, I am the servant of the Lord. His will be done.

Translated from the Swedish by Linda Schenck. Translations of the other three novels in the Women and the City series, The Spring (tr. Linda Schenck), The Angel House (tr. Sarah Death), and City of Light (tr. Linda Schenck), have been published by Norvik Press. Reproduced by permission of Bonnier Rights, Sweden.

Back to Top

Author

Kerstin Ekman is one of Sweden’s most acclaimed contemporary authors. Her novels translated into English include Blackwater (Doubleday), Under the Snow (Doubleday), The Dog (Sphere), and The Forest of Hours (Chatto & Windus). Sista rompan (The Last string), from which the story in this issue is excerpted, is the second volume in her Wolfskin trilogy, which also includes God’s Mercy (University of Nebraska Press) and Skraplotter (Scratchcards). She was elected a member of the Swedish Academy in 1978, but left her work there in 1989 in response to the academy’s failure to take a firm stand concerning the death threats posed to Salman Rushdie. She has received many national awards such as the August Prize and the Selma Lagerlöf Prize, as well as the Nordic Council Literature Prize. She lives in Roslagen, Sweden.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

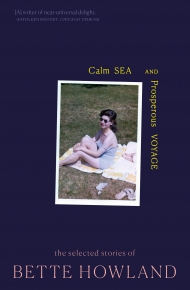

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.