A Question for My Father

• Kerstin Ekman | Selected and Introduced by Dorthe Nors • May 2, 2014

I have a memory of my father. It is suspended in time and space, as memories tend to be. I don’t know where we are, but I can hear his voice clearly. It is teasing and yet very intense. That’s what he was like when he was being serious. Incorrigibly sarcastic. Good Lord, girl, he is saying. Haven’t you noticed, a whole society is being built right around you? Was I sitting at the piano at dusk? He liked that. I must have said something that exposed my dreamy-eyed ignorance of what was going on around me. Sweden was just beginning the social upheaval that would throw us through a giant bell-shaped curve from cheerful optimism to bewilderment and panic. I knew nothing of it. I played Satie’s Gymnopédies. Until that moment, whenever I heard the word society I pictured the town hall. But my father wanted me to picture a superstructure. A construction site, with constant pounding and banging going on all around me. The everyday sounds of a growing industrial society. Power drills and screeching compressors, the entire cacophony surrounding me—that was society!

I grew up in a small town, born with the coming of the railroad. It had already completed an earlier phase as a garden town, a petit bourgeois idyll where poverty was concealed behind lilac bushes. My childhood scents were peonies and ripe gooseberries. The mighty men of the town ordered linden trees to be planted along the roads. The linden is the tree of life. Its heart-shaped leaves still send me powerful messages. But this was the fifties and the gardens were being dug up. The linden trees blocked the construction of department stores and houses, and were felled. The women who had stalls on the market square, like my grandmother with her sweet stand, were driven out of the heart of the town by the health authorities. The market became a parking lot. I wandered the drab streets. People worked in factories where ball bearings were manufactured and brake discs cast, or spent long afternoons at school, being stuffed with facts like sausages into their casings. They would soon be delivered, shaped and finished. Dreamy-eyed and utterly ignorant, and with a hunger that had nothing to do with beef stew served with pickled beets, I wandered that superstructure of my father’s society, unable to understand what I was seeing. When does a person figure things out? It doesn’t happen when you are being stuffed into your sausage skin. Every now and then you figure something out. Perhaps at the piano at dusk or while wandering like a stranger through the adult world. I walked along gravel roads dotted with dirty-rainwater puddles. The new houses were a functional gray and their stucco was striped by the rain. For a very long time there had been nothing built here for any other reasons than ones we call sensible. I despised the men who had created this hideousness. I wanted to hold them accountable. But I couldn’t. I didn’t even know who they were. I only knew they were united in a system of ownership. Perhaps we were all, in some dark way, united in this drab world in which greed and the desire for power was rewarded. The diametric opposite of what we always heard preached in the tirades after morning prayer at school, us poor little sausages. We hadn’t been learning facts. We had been toiling over our literary legacy in school anthologies. And the whole time, the mighty men of the community were hammering away at their construction. I hated them. And I laughed at them as they trudged through the snowy slush in their galoshes on the way to their lodge meetings and their municipal councils.

At the same time I was taking my melancholy adolescent walks around Katrineholm, the small town where I grew up, a sociopsychological survey of the community was being carried out. In the 1980s, thirty years later, it was followed up with a second one. Both times Katrineholm was found, unambiguously, to be a healthy, happy community of the Social Democratic model. I devoted eleven years of my life to asserting the contrary in four novels: Witches’ Rings, The Spring, Angel House, and A City of Light, published between 1974 and 1983. It is the task of an author to shed light on that which has been disavowed. One of the most important assets of a writer is the instinct to identify what is lacking in a society. What is living in the shadows? Hidden in the darkness, forsaken. And where does that asset originate?

When I wrote A City of Light, if not before, I realized that it came to me out of my dreamy and shapeless teenage rebellion. Back then I was hungry, but not for beef stew. Back then I dreamed. Not the municipal planners’ grandiose and expansive dreams of town centers and people liberated from their past. Young people dreamed different dreams. They still do to this day. When I grew up, the term teenager didn’t exist. I may have been a teenager, but I was expected to behave and preferably also to think like a sensible young lady. I was fitted out in a hat, a purse, and low-heeled pumps. I was certainly not expected to have sexual preferences, let alone a sex life. I was a transitional phenomenon in ladies’ wear. But I was not a problem. Today, everyone is more or less terrified of the state known as youth. Its music, its fears. Yet we barely listen to their dreamy lyrics about the raging hunger for what we have not been able to give them. Their hunger for that which is lacking here, where we live.

When my father told me a whole society was being built around me, he was not thinking primarily about the Swedish political superstructure that later became known as folkhemmet, the home for the people, the aim of which was to distribute comfort and material welfare as fairly as possible. He was thinking about that to which he was committed with all his heart and all his building talent—the dream of technological progress. He was participating in the construction of a clean, comfortable, and sensible society. When he bought his first Volvo, a PV444, known at the time as the car for the people, he rolled out into the soft, rolling, leafy countryside in a dust cloud of dreams. It eventually transpired that substantial clouds of exhaust accompanied those dreams for the people. I don’t mean to make fun of him, and I would never have wanted any other father, ever. He was funny in his sarcastic way. He was creative—verbally and technically. He had a great deal of warmth and lots of stories and songs for a freezing child in a drab society. But he was a romantic in terms of progress. For him there was hardly a problem technology and scientific research would not be able to solve. Everything I have considered, all my life, to be the degeneration of society and civilization and the road to destruction, originated in his dream. How could that be? How could an intelligent and insightful man’s vision of society be transformed into a nightmare? That is my question, and the deeply personal fact that I am asking it long after his death is what has prompted me to write the books I have written about my society.

The town was no older than the railroad network. The railroad was laid out like a ribbon of bright, chugging time across the meadows and farms. People were always saying that this kind of place had no history. But history was precisely what it did have. It was history. In its unpretentious drabness and confidence in common sense, it became my image of how contemporary Sweden developed from its peasant past. The history of the town was well documented in commemorative volumes and anniversary publications. The enterprising businessmen who began by transporting timber and manufacturing horse-drawn harrows became known as the town fathers. Their statues were erected in parks, their graves marked with large monuments, their oil portraits hung in the town hall. They had complimented themselves and each other on their entrepreneurial abilities, their fine initiatives, their resourcefulness, and their visions of the future.

In this little town’s entire journey into contemporary history, not one single woman was given a place. But I knew there were enterprising women in the community and thus in history. I knew it because I heard it from their own lips. My grandmother, my mother, their friends. Women’s talk is a source that historians of the strict, male school have always disregarded. I grew up with women’s talk. It is a special fabric of stories I carry within me. When, from a distance of decades, I began to examine it and supplement it with material tucked away in archives and libraries, I saw that the main theme in the tapestry was a constant: work. But not the work that has already been described in literature. No, women’s work. Does that sound dull? Endless floors to scrub, board after board, first with a scrubbing brush and soapy water, then by me with words. With language. The making of a dress with special tucks and lining and invisible seams, is later transformed with language into a declaration of love from a daughter to a mother in my novel. Or weaving a rag rug of the past. Strong Rags was one of my working titles for Witches’ Rings. Strong Rags smacked too much of social realism to me, and this was not social realism—to me it was poetry. The poetry of everyday things.

Writing about something that has not been described before is like walking through a forest in spring. The foot responds. The earth is young. I must admit I had my doubts as to whether readers would grasp this poetry of everyday things when it was about washing and cleaning and cooking and sewing and dealing with children—that entire female world of work and worries and joys that had been shrouded in shadow and oblivion when the men wrote their histories of society. But I had no need to worry. Readers shared with me, as the books were published, their thoughts about this kind of writing, and first and foremost they shared their own memories. Just think if I had had them from the outset! What I slowly began to realize, as I wrote my way into the history of my society, of my mother and her mother before her, was that women’s lives are a rich and complex weave. The work that comprises the furrow running through it consists not only of work to support their families, but also of all the work they invest in their everyday concerns and chores. This work was not part of the productive, market-oriented labor, preferably oriented toward the export market that made Sweden wealthy in the post-war era, the work described as the building of a society. It was reproductive work, and reproductive work was neither depicted in the portraits of society builders nor otherwise taken into account. It was repetitive, recurring work. Its timeline was not the linear time so well exemplified in Swedish history by the bright ribbon of the railroad. For women, in contrast, time was cyclical, reflected in their seasonal chores in their homes, in their experiences of sexuality and childbearing, in the way they nursed the sick and dying. Their entire perception of life belonged to a paradigm that has now been declared obsolete and forsaken. Their perception of life valued caring and thrift. These are hardly the virtues of the industrial society. When I discovered women’s perspective, I found my method. I would examine society as what we might call an outside observer: woman.

My novels from that period are based on women’s perceptions and interpretations of society. From page one, their perceptions make the prevailing optimism about the future a relative concept. Their lives took place within the walls of society, behind its facades. Their view of life made its own pattern underneath the official one. If their unpaid work were written into history, it would change that history. I discovered that again and again while working on those novels. There was pleasure in that discovery—and there was a great deal of anger. Whenever the anger threatened to get the upper hand, I was glad to have a heritage to fall back on—not only my mother’s cornucopia of stories but also my father’s irony.

In a society undergoing enormous, rapid development, people tend, in more than one respect, to become obsessed. Obsessed with society. I have thought of that phrase many times. Every night we sit at the altar from which the sacrament of a secularized society is given: breaking news and commentary. In the course of each evening, our existence is structured into episodes describing the world in which we live. Structured in financial and political terms. One might wonder what this mental manipulation does to us. One might also wonder what we would have been like without it, and whether it is even any longer possible for us to evade its firm grasp, turn a deaf ear to the voice. Can we seriously allege that we possess attributes that are not part of this structured world? That we are strangers here ourselves? That we are different in any way, in any aspect of our existence? Strangers. Savages?

It’s not only the global media society that has our souls in its firm grasp. In The Spring, a rebellious young man ponders the question of what people, or rather what sides of people, have surfaced into the daylight and been taken advantage of by the society in which he lives. He is aware that there are other sides, other ways of relating, but they are shrouded in the deep darkness of night:

People had moved from living as tenant farmers, on farms and in shanties, to become station clerks and lumberyard hands, washerwomen, foundry men, waitresses, and boiler men in this community.… Beyond their energy, their strength, their sense of community and their strong moral fiber, there must also have been something tentative about them to begin with, something that belonged to the forest and the night, something aberrant and illusive. A kind of dignity, he thought. Maybe goodness. He tried one word after the next, but like piety and goodness they were already labels for people in daylight and there were none left for the ewe and the lamb, for the root and crown, the waves against the cliff, the dog’s tongue, the rain, the grass and the warm hands.

When I was working on those books, it became increasingly important to find the things that belonged to the night and the forest. The illusive things. The things that live deep in the shadows. In oblivion. But which somehow are still part of the people among whom I live. These things came to me during intensive periods of work, where I was fully preoccupied, perhaps even obsessed, with society and its people. They came to me as images and dreams, and they were very powerful.

A creature, neither man nor beast, appeared at the edge of my consciousness. He nestled into my dreams. Assumed a form I could not reject but not explain either. Different. Strange. Maybe a savage. He came from the forest. A troll. I hesitated to use the word. In my novel The Forest of Hours it appears a couple of times. But it is always used by other people to describe the creature Skord; he does not like it.

In the mountain villages in northern Sweden, where I lived for many years, people sometimes call someone a troll. That person has no tail and lives like the rest of us in a house with district heating and a satellite dish. But a troll. Different. Alien. Maybe dangerous. This remnant of the savage in us; the part of our psyche that is shrouded in darkness and foreign to us has dangerous potential in contemporary society. In the past, the Sami of northern Sweden made room for this alienation, these trolls, in their culture. In fact, they took an important position. These people became the guides, the healers, the carers. These people, the boundary crossers who were able to shoulder the pain of the entire community, were known as shamans.

For many centuries Eastern Orthodoxy had its fools for Christ, who pursued their criticism of lust for power, cruelty, greed, and dishonesty like theater of the absurd, in the very midst of their society. The holy fool dragged his dead dog on a leash across the market square. He prostrated himself in church, prattling and screaming in the middle of the sermon. In our thoroughly regulated society it is difficult to pursue being different except through psychosis or criminality. The alienation of the artist is so obviously adapted to the contemporary demands of the free market that one can hardly say that (s)he takes similar risks to those of a mass murderer or a holy fool. Our society is infinitely permissive as long as none of its monetary values are threatened.

Modernism, initially boundary crossing, dangerous and deeply provocative, fell apart in the infinitely permissive and fundamentally indifferent modern society, owing to its demands for repetition and intensification. But where a different cultural climate prevails, modernism resurfaces as dangerous and risk filled. This is clear in the oeuvre of authors today who find themselves in profound conflict with fundamentalist forces, religious and, above all, political. Today writers from the Third World grapple with conflicts and boundary-crossing behavior that makes them a danger to some of the elite, the powers that be. This risk-taking has also proven artistically fruitful in their work. Fundamentalist threats are aimed at immigrant writers all over the world, and they are exerted without our ever knowing it. These threats work their way in, become fright and shame—and, in the long run, self-censorship. We must support and protect these individuals to the best of our ability when they are subjected to threats that are sometimes diffuse, but just as often tangible and harsh.

The horror experienced by the religious when the world they regard as sacred is violated is not particularly difficult for us to understand, although we live in a secularized society. There are horrifying, hateful, and objectionable aspects to the oeuvre of authors whose work moves us deeply. Hurtful aspects. Anyone who seriously questions what it is to be human must from time to time find himself on the periphery of humanity and the outskirts of society. This blurry region where shadows step forward, where darkness takes shape and where fragmented and repressed emotions and fantasies gather and become perceptible is, to me, the forest.

The forest was once the screen on which people projected their fantasies about the unfamiliar. About the strange and savage. About evil. Today it has been incorporated into modern technological and economic thought, full of human endeavor, and simultaneously completely known and unknown. Who walks in the forest?

The screen of contemporary mankind has been moved to metropolitan areas and into the streets, where anything that is alien is regarded as evil. Where terror resides. Almost half the people in Sweden today live in villages or exurbs with fewer than ten thousand inhabitants. We who live in rural areas are governed by the same economic system that governs people in metropolitan areas. The mental decay there is not very different. We do, however, take pleasure in somewhat different things. And one thing is certain, Sweden’s rural areas have been in the shade. They receive no media attention. Their decay and impoverishment apparently do not concern anyone but the people who live there.

Some critics referred to the people in my novel Blackwater who made money out of the natural resources in rural areas as mafiosos. Anyone who can call the entrepreneurs who profit from the development of rural areas mafiosos has failed to notice that the same economic system on which their success is based applies to the entire country, and to all of Western Europe for that matter. But somehow it is more difficult to recognize ruthless exploitation and greed in people who wear dark suits and speak without a dialect. Their business apparently makes a more organized impression. All I did in Blackwater was simply to shift the focus to the periphery, to a mountainous world where the vulnerability of the countryside and the people can still be recognized. The shadow that follows the entrepreneurs, the financially successful men, in both places is known as violence. Fatal violence. It just becomes so much more obvious when the focus shifts to the far edge of the habitable world. The forest has been felled; the earth has been destroyed and rutted by enormous timber harvesters.

In the same way as the memory paths of the Sami in the mountains vanished when the earth was crisscrossed by off-road vehicles, by snowmobiles and racing motorcycles, the memory paths and footpaths in the forest have also disappeared. The forest that is now growing in the clear-felled areas will not hold the memories, dreams, and knowledge of the people of its time. Those days are past.

Perhaps the forest can still be a source of renewal and inspiration to people who come to it freely, wander through it, feel at home in it. Why it is that way for me, I can’t really say. As a child I lived on the outskirts of a small community, at the edge of the forest. It was a natural place of refuge. It was where I spent most of my time while my father was busy building that society of his. What I was thinking, what I was dreaming and fantasizing about with the strong scent of bog myrtle and moss around me, I no longer recall. But those scents can still sometimes evoke a shadow of a memory that flickers by like a moth in the light of a summer night.

Imagine if we could get back to our emotions and experiences and be in them, as if in a room. If we could read them, collect them and once again sense their essence, as if they had been locked up in a sealed box only we knew the art of opening. Some people believe we die early because we live lives that are both tiring and repetitious. Our emotional experiences, our visions and our moments of recognition are fragmented and wasted, and that makes us downhearted and confused. This is very difficult to change, because it appears to go hand in hand with the obscurity and transience of our emotions. With the ineptitude of our comprehension and with the capriciousness and ambivalence of our memories.

This talk was given at a writers’ conference at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art on Sunday, April 23, 1995, and was translated from a Danish translation by Jens Juel Jensen, the Swedish original not being available, by Linda Schenck with the assistance of Julie Westh Soerensen and Dorthe Nors. Reproduced by permission of Bonnier Rights, Sweden.

Back to Top

Author

Kerstin Ekman is one of Sweden’s most acclaimed contemporary authors. Her novels translated into English include Blackwater (Doubleday), Under the Snow (Doubleday), The Dog (Sphere), and The Forest of Hours (Chatto & Windus). Sista rompan (The Last string), from which the story in this issue is excerpted, is the second volume in her Wolfskin trilogy, which also includes God’s Mercy (University of Nebraska Press) and Skraplotter (Scratchcards). She was elected a member of the Swedish Academy in 1978, but left her work there in 1989 in response to the academy’s failure to take a firm stand concerning the death threats posed to Salman Rushdie. She has received many national awards such as the August Prize and the Selma Lagerlöf Prize, as well as the Nordic Council Literature Prize. She lives in Roslagen, Sweden.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

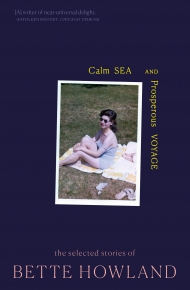

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.