The Practice of Murder

• Kerstin Ekman | Selected and Introduced by Dorthe Nors • May 2, 2014

I do not have much confidence in medical science. That was a subject on which Harms and I were, for once, of the same opinion. He alleged that the human body is largely self-healing. Not entirely of course. We do all die in the end. But it was his view that three-quarters of all illnesses will heal on their own. He claimed to have scientific proof of his conviction.

I believe there is something to this. We can perform surgical interventions with some degree of success. We are skillful in terms of splinting broken bones, removing slivers from the eye and cleaning open wounds. Such simple handiwork was the province of field surgeons and barbers long before medicine was a subject for academic study in Sweden. We seldom cure what we are unable to incise, remove or splint. But we can ease suffering.

That also seems to have been Johannes Harms’s special branch of medicine. I had no idea the extent to which I would have to pursue it in order to keep his practice running. I use a dropper to relieve the pain of tortured flesh and the misery of tormented souls. I prescribe opium and potassium bromide of different patented pharmacy brands. Laudanum was what he prescribed, and I continue to give it to women who never cease to be terrified of pain and grief. Two patients of Harms are even addicted to cough medicine containing opium, so addicted that they actually have to collect their prescriptions from different pharmacies in a predetermined order to keep the pharmacists from noticing.

Once I became the autocrat of the Harms practice, I tried, purely out of concern, to slow down the flow of tranquilizers and painkillers. That led to pleas, screams, and hysterical seizures. Indignant husbands wanting peace and quiet at home appeared in my waiting room. When I explained the risks I was taking by writing such prescriptions far too frequently, my fee was raised. I pocket that type of remuneration. There is no need to account for it to Elsa Harms, since I am the one taking the risk, not her.

At some appointments I am required to provide immediate relief. I stand there with my dropper, administering the much-coveted tranquility as drops in a glass of water.

Drop by drop I am alive. Drop by drop time and death are also forcing their way into me. He who cannot act, slowly dies. Many of my pleading patients are seeking a cure for boredom. The best thing about such patients is that I do not have to see them undressed. I do not even need to touch them.

There is no getting around the fact that the practice of medicine is generally unpleasant and contains a sizeable measure of voyeurism. That part was most certainly involuntary for me. I had no desire to peek under anyone’s underwear.

In my mother’s dreams, the medical profession was an exalted one, and I was going to be the person who united medical science with homeopathic practice, elevating it to a higher status. She was not ignorant of the fact that homeopathy was pursued by gentlemen who took rooms at boardinghouses and practiced their art there wearing white coats, of course, but most frequently also worn-down shoes.

It would have been bad enough for me if the voyeurism of the medical profession had ended at the examination of fistulas around the anus and lumps blossoming like obscene roses from the female breast. But at medical school we had to participate in the opening and incising and poking about in the bodies of the dead. I fainted and I vomited but they made me complete these macabre exercises. My mother, with what we referred to as her self-sacrificing nature, had me trapped in a program being paid for by a merchant of whose magnanimity and generosity I was frequently reminded in the early days. Later the subject became taboo. The insinuations of my classmate Hoppe and my outburst at home had made it far too awkward.

In any case, I completed medical school in my way. I was most certainly not part of the crowd who played tennis in the courtyard of the Karolinska Institute. But I had imagined that I would move up a peg in society once I was working in a practice. I did manage to achieve the rank of second lieutenant at the Garrison Hospital, and I am sure I could have been promoted even higher. But then that fateful matter with Elise took place, and I was overwhelmed with terror. For weeks I expected a police commissioner to come tramping into the clinic in his high boots and with his hand on his sabre, demanding that I come along to the headquarters in the paddy wagon. In this weak state I ended up inspecting the genitals of streetwalkers and treating their diseases, without the energy to move on. I was borne along on a stream of coincidences like the rubbish in the Stockholm canal, and began to feel nothing but disdain both for myself and my work.

Now I want to hang on to the status I have finally achieved. But Elsa Harms is a threat to my sheltered existence. She wants to sell the practice.

On the days when I know she is going out—most weekdays—I interrupt my afternoon sick calls and hurry to the flat. On the way I buy something from a pastry shop and, bag in hand, wait on the street until I see Frida coming from school.

I see her from a distance because she wears a Scot’s plaid beret she calls her tammy, though it is really known as a Tam o’ Shanter, after the protagonist in the Robert Burns poem. English is the favorite language of the pupils at the Athenaeum girls’ school she attends. They consider it modern and exciting, in contrast to German and to the French that is so warmly cherished at more traditional finishing schools for young ladies.

Her walk from Stora Bastugatan is long enough for her to be rosy cheeked when she approaches me. In damp weather the loose strands from her braids curl up. This frizz on her otherwise tight plait has a powerful effect on me. I feel it at my groin. Excitement at the sight of little frizzy hairs, no matter whether they are at the throat, in a set of bangs or a braid, is a sensation I have known since I was a schoolboy. But in those days the stimulation was mixed with a heavy scent of rose oil and unaired clothing. Now it is pleasurable.

The first time I met her after school I pretended, of course, that our encounter was entirely coincidental. We no longer have any pretenses. She knows that I wait for her and is quick to ask the maid to prepare some coffee when we get upstairs. At the table she talks nonstop, and that good, warming flow of words feels quite physical; it seems to go straight into my circulatory system. Although of course what warms me and livens me is not what she says, it is her voice. She talks about her teachers and her classmates at the Athenaeum and most of it is girlish chat, innocent gossip and little stories. But now and then she shares her worries with me. Her jealousy! The girls apparently go head over heels about some of their female teachers, and I assume it is all perfectly innocent. Still it upsets me and I try to change the subject.

She adores sugared jelly donuts. It is wonderful to watch her eat them because she has to lick her lips free from the grains of sugar that adhere to them. The rosy tip of her tongue protrudes and I feel heavy where I probably shouldn’t and find myself panting. But the whole thing is so innocent that I cannot reproach myself for it at all. She doesn’t even know about it. I am a grown man. I wonder if she ever thinks about that? Would she be afraid of me if she thought about it?

Two weeks ago Elsa Harms came home unexpectedly while Frida and I were having our coffee. However, no explanations were called for. She was upset about something else entirely and asked to speak with me in private. We went into the office, and without prelude she sat down at my desk and left the patient’s chair to me. I don’t think it was intentional. If she has two choices she instinctively chooses the one most belittling to me. At first I hardly heard what she was saying. The contrast between Elsa and Frida was a shock to my entire nervous system.

What she was talking about was, of course, the projected sale of the practice. Until that day she had had very few bids. Now a physician with a Kungsholmen practice had finally made what she called a disgraceful offer. She was extremely upset. I told her that since the practice had already been for sale for quite some time, she could not expect the bids that came in to be anything but lower and lower. She would have been better off to accept the first one that came her way.

“I have to leave. I have three more house calls to make this afternoon.”

That got to her. In fact it had more impact than I had really intended. When I came back for dinner she was extremely pensive.

“Don’t go,” she said when I got up from the table. She sent Frida off to do her homework, and we stepped into the drawing room. She took a bottle of Madeira and two glasses from the sideboard in the dining room, and after pouring us some she raised her glass with a singular smile. She certainly is unaccustomed to showing me kindness.

“We have to come to an agreement,” she said.

I said nothing.

“I think it would be a mistake to sell the practice,” she went on.

I believe I shrugged my shoulders.

“You see. . . How shall I put it. . . We have to talk about what endows a practice with its value.”

Now she’s getting to the point, I thought, saying in a light-hearted tone of voice: “That’s right, a practice is more than a set of furniture and a few copies of oil paintings and some well-thumbed copies of the Svea almanac. Or a collection of instruments in a vitrine and a medicine cupboard that needs constant refilling.”

“You don’t say,” she said sharply. She is sly but actually quite simpleminded. “If not,” she asked, “what does give it value in your opinion?”

“The value of a practice is determined by the physicians who run it and by whether or not the purchaser intends to keep the former doctor’s patients.”

“Are you planning to open a practice of your own?” she rebutted. Then, without waiting for an answer,,“I don’t suppose you could afford one.”

“I have borrowing options,” I said. “It would be considered a good investment because I already have a list of patients. I wouldn’t have to start from scratch, after all.”

“But it was my husband who got you your patients!”

“That may be so,” I said, “but they are mine now.”

There was no way she could know that the last thing I would ever do would be borrow money. I had finally worked my way out of debt to the heirs of Schöler the merchant.

“Stay,” she said.

I pretended not to know what she meant.

“Stay here. Keep the practice running. I believe it would be the most advantageous solution for both of us.”

I thought about Frida. I only have a single unpleasant memory involving Frida. Once she had looked up from her meal and asked, “That house opposite ours when we lived on Klara Norra Kyrkogatan. The flat across from ours. Who lived there?”

Both Elsa Harms and I had kept silent as Frida musingly poked at her mashed root vegetables. She had gone on, as if to herself, “It had red curtains, always pulled. Except for one evening. Do you remember the time there was that terrible snowstorm? It was early winter. That evening there were girls at the window, looking out. Or, well, women. Young women. In nothing but their camisoles. You often went into that building, Uncle Pontus. You must know.”

Elsa Harms hurried to reply. “It’s a boardinghouse for young women,” she explained. “Finish your dinner now and stop making a mess with your fork.”

That was all. It took place a couple of years ago. I am afraid Elsa Harms will not be as discreet about the realities of life in the future. Frida is older now. She is about to be inaugurated into the stifling world of women. Although she is not likely to find out what goes on at those so-called boardinghouses for young women, she will probably soon have some sense of what happens between a man and a woman. She will lose her purity. In fact that is her mother’s ultimate aim, she wants to see her betrothed, preferably before she has finished school at the Athenaeum, and then married to a promising or already well-established man. If I left the practice I would have no more chances to spend time with Frida. And I would have to return to a world the filth of which she cannot imagine. There is nothing but my position in the Harms practice between me and a return to the hospitals, and probably also to Eira and the inspection clinic for venereal diseases. That was where I earned my qualifications.

But we are playing a game, Elsa Harms and myself, so I was careful not to say yes. I shook my head and drank my glass to the dregs.

“I must be going.”

“Consider the matter!”

“No,” I said. “I want to be independent.”

I was playing for high stakes, because the next day she might just have accepted that miserable bid and sold the practice. She hasn’t, though. I have been waiting for ages for her to make the next move. Yesterday she did.

“Revinge,” she said after dinner. She calls me by my last name, as if I were her coachman or concierge. Frida must have heard from her tone of voice that we were going to talk business again, and she was quick to sneak off to her room. We were standing in the drawing room again, but this time without Madeira glasses.

“We will have to become partners,” she said.

I would have very much liked to have a drink to sip while biding my time.

“You might just as well borrow the money and invest it here,” she said. “Then you wouldn’t have all the risks involved in opening a new practice.”

Oh, woman, you have no idea what you are saying. You know nothing about how I slaved to repay the Schölerian loan. Nothing about how my mother came into that money. No, never borrow! Never ever.

“No,” was all I said.

“But Revinge! You are being unreasonable.”

“Not a bit,” I answered.

Now I have to commit something to paper that probably took place in my brain during a fraction of a second and that I managed to get out without losing my composure. It gave me a sense of sudden exaltation I recognized. I had experienced it before, when acting on instinct. It happens to me when I am playing secretively with something in my pocket. It happened to me when Johannes Harms tumbled to the floor from his examining table. But now I didn’t show it.

“Bring in the Madeira,” I said. “We may have something to celebrate.”

“What do you mean?”

I merely smiled and she really did fetch the bottle from the sideboard in the dining room and two little cut-glass goblets. When I had some Madeira in mine I did not raise it, but simply said, “Marry me.”

I had the pleasure of seeing Elsa Harms completely dumbstruck. She looked idiotic. The coachman, the concierge, the shopboy—all the subordinate individuals she called Revinge—had, for a moment, made her speechless.

“Let us raise our glasses,” I said. “I am proposing. It will be a pro forma marriage, naturally. Consider the matter! But think practically, Mrs. Harms.”

I drank my glass to the dregs and set it down with a little clatter.

“I will see you tomorrow.”

Then I stepped out of the room, still as exalted as if I had had champagne in my veins instead of blood. Not until I was in the stairwell did I begin to snicker.

This excerpt of The Practice of Murder was translated from the Swedish by Linda Schenck for this portfolio. Reproduced by permission of Bonnier Rights, Sweden.

Back to Top

Author

Kerstin Ekman is one of Sweden’s most acclaimed contemporary authors. Her novels translated into English include Blackwater (Doubleday), Under the Snow (Doubleday), The Dog (Sphere), and The Forest of Hours (Chatto & Windus). Sista rompan (The Last string), from which the story in this issue is excerpted, is the second volume in her Wolfskin trilogy, which also includes God’s Mercy (University of Nebraska Press) and Skraplotter (Scratchcards). She was elected a member of the Swedish Academy in 1978, but left her work there in 1989 in response to the academy’s failure to take a firm stand concerning the death threats posed to Salman Rushdie. She has received many national awards such as the August Prize and the Selma Lagerlöf Prize, as well as the Nordic Council Literature Prize. She lives in Roslagen, Sweden.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

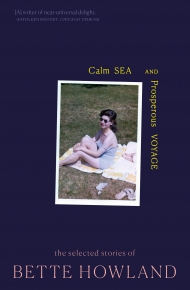

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.