Excavating a Life: Part II

• Sam Stephenson • October 1, 2013

Earlier this year, Sam Stephenson spent four weeks in Japan, walking in the footsteps of photographer W. Eugene Smith, whose life and work he's been studying for fifteen years. Sam is working on a biography of Smith, and collaborating with Chris McElroen on Chaos Manor, a multimedia adaptation of The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957-1965. Sam and Roland Kelts, whose Focus: Japan portfolio appeared in APS 1, talked about his trip to Japan, eccentricity, assumptions about progress, and a culture that cultivates paradox.

RK: Eugene Smith, your subject, was known to be an eccentric man. After so many years of researching Smith, what new insights did you learn about him during your time in Japan?

SS: There are a couple of things that come to mind. One is the fondness expressed for Smith, the really moving expressions that people made about him. Several of our interview subjects cried when talking about him. I’ve made 120-some trips to New York in the last fourteen years, researching Smith and the Jazz Loft Project. I’ve interviewed almost five hundred people now. In New York, people thought he was a pain in the ass. In twenty-some interviews in Japan, that never even came up. People loved him. So was there a different Eugene Smith in Japan, or were they just more accepting of his, as you said, eccentricities?

RK: Based on your impressions of Japan, does it seem like a place that might embrace eccentricities even more openly than New York?

SS: I did not find it a place where eccentricity was on display a lot. Some of our interview subjects were sort of hidden behind a… presence, a facade of a human presence. There was some eccentricity. This one man in particular, his name was Kazuhiko Motomura. He’s in his mid- to late-seventies now. He was a career employee of the local tax office, a lifelong civil servant and he looked like it: polite, kind, understated, unassuming. But he grew up watching Kurosawa films and he got into visual art from that and then black and white photography. He became a publisher of fine art photography books. He’s published only five books in his life. They happen to be five masterpieces. Three of them by Robert Frank and then one by Jun Morinaga, who was one of Smith’s assistants, and then a fifth book by a man named Masao Mochizuki. He only published five hundred copies of each one and they sold for about a thousand dollars apiece. It’s remarkable how painstakingly and thoroughly and how finely he published these books.

Motomura was a guy who probably would accept Eugene Smith’s eccentricities, but his appearance suggested otherwise. He appeared to be conservative and well-mannered and conventional. Yet, in New York, you find people who put forth the opposite images—hip and unconventional—who thought Smith was just an asshole.

RK: You’re basically excavating Smith’s entire life, looking through an archaeological dig to figure out who he was, what drove him, what his art was like and what went into making it—did your experiences in Japan help you understand in any way why Smith became so attracted to a country thousands of miles from his roots?

SS: I’m still grappling with that. Visually, aesthetically, Smith was all about contrast. One of the signature traits of his photography is there’s a pure white and there’s a pure black in every one of his master prints. And then there’s every tone in between. I think he was drawn to trying to reconcile extremes. That’s what he tried to do visually with his printmaking, his darkroom printing.

Would it make sense if I were to say to you that he found a culture in Japan that was trying to reconcile extremes, too?

RK: I was just going to say that one of my favorite classics of Japanese literature is *In Praise of Shadows* by Junichiro Tanizaki. It’s a meditation on a very fundamental Japanese aesthetic, which is finding the subtleties between what you just said actually, pure white and pure dark, and exploring the shades and nuances at the darker end of the spectrum, fine-tuning the tones, so to speak. Tanizaki contrasts Japan’s traditional fondness for the muted or subdued with the West’s emphasis on striving toward light as a sign of growth and advancement.

SS: I read Tanizaki while I was on the trip. I read his *Seven Japanese Tales,* including his story “Portrait of Shunkin.”

RK: So you know he’s obsessed with that imagery in all of his work. *In Praise of Shadows* is his kind of aesthetic meditation on these questions.

SS: Smith must have felt at home there for these reasons. He was from landlocked Kansas, where it was flat as a tabletop. But he told his Japanese-American second wife that he felt like he was from Japan in a former life, in a previous life.

RK: I tend to think of Japan as a culture that historically is not only comfortable with what Westerners tend to think of as paradoxes, but that in some ways welcomes and even cultivates them. You see that going back centuries—in a way, the whole country is something of a paradox. This archipelago off the coast of Asia, with very little space, few natural resources and years of self-imposed isolation, becomes one of the most powerful countries militarily in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, after it was opened to trade, and then becomes the second largest economy in the world in the second half of the twentieth century, after being flattened in World War II. On paper, there are several reasons that shouldn’t have happened. So maybe Smith was drawn to something almost philosophical in the history and character of the people.

SS: I like your use of the term *paradox* because it’s a term that Smith used often. When he created his mammoth study of the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the 1950s he used a phrase *equilibriums of paradox* to describe what he was trying to do with that work.

RK: Did Smith have any interaction with the jazz scene in Japan?

SS: I don’t think so, except through the radio. He did listen to a lot of radio when he was in Tokyo. But I think that what Smith loved about jazz is the same thing the Japanese love about jazz. I think that it has a lot to do with the blues. You put me in touch with Haruki Murakami, who talked about Sonny Clark. I’d asked him specifically about Sonny Clark’s popularity in Japan, which is very unusual and extraordinary; it dwarfs his popularity in the US. Murakami responded that Clark’s music had a minor blues quality that was perfect for the jazz *kissa,* the jazz coffee shops that proliferated in Japan the 1960s. Something about the mood of Sonny Clark’s music just was the perfect match for that. And I think that’s what Smith liked.

RK: Did you tell me earlier that when Smith was in Minamata he drank a fifth of whiskey every day?

SS: Yeah, he drank a fifth of Suntory Red. He drank a fifth of Suntory Red and ten bottles of milk everyday. When we were in Minamata, we went to the store where he made that purchase every day and the same family that owned the store back then, the Moziguchi’s, still own the store today. They remembered him very well. My interpreter, Momoko Gill, told me that Mr. and Mrs. Moziguchi talked about Smith was if he was still there. They have a photo album, like a scrapbook, with two of Smith’s vintage prints in it. He had given them the prints as gifts. That’s where he bought that liquor.

RK: What about your own personal impressions of Japan the first time around? As someone who grew up in the States and had been pursuing Smith in Pittsburgh and New York and Kansas and so on—here you are, suddenly in this very distant culture, still quite alien to a lot of Americans. What are your own impressions?

SS: I think that I’ll keep visiting Japan for the rest of my life. I found myself trying to think of projects that would send me back. I sort of have this weakness for interviewing elderly people. They have things to say that are outside of my experience, because they come from a former time. I found it really interesting in Japan. After twenty-some interviews in Japan—the youngest we interview was Takeshi Ishikawa, Smith’s former assistant in Minamata, who is now sixty—I sensed a kind of melancholy perspective. Maybe it’s a detachment from the youth culture. I’d like to explore that a little more.

RK: Do you think you’re drawn to do more work in Japan because of this particular generational dynamic? After the war, Japan changed so quickly under the watch of today’s elderly citizens—is that what, as a writer, draws you to explore Japan?

SS: It is. As a writer what drew me originally to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which is where my interest in Smith began, is that that city embodies many questions that are in some ways theological at core. Pittsburgh has lost about sixty percent of its population from its peak, so there’s a collision between this kind of forward thinking culture that we have in America and what you can see in Pittsburgh. We’re always trying move forward in America. *Progress* is so important to us. A city like Pittsburgh forces you to rethink many assumptions about progress and what’s really important.

I feel that in Japan too, I think I feel some sort of powerful question of values. What are we doing here on this planet? What’s the real meaning behind this rush forward? I heard that question in some of the voices of people we interviewed in Japan. Smith’s Minamata project asks those questions, too, because that work is about a town that was ravaged by corporate pollution. The economic values that led to the decisions made by that company ended up with a very dramatic wound on the people, a dramatic, tragic repercussion.

RK: Listening to you, I’m thinking that if those questions have been coursing beneath the surface of Japanese life, daily life in Japan, even in Tokyo, this latest catastrophe (the earthquake and tsunami and nuclear fall-out in March 2011) has in some ways exposed them for most of the country.

You know there’s a generational subtext to what’s happened in northern Japan, because by far the majority of those residents living in those coastal villages and seaside towns are the elderly. As you observed, Japan is an absurdly comfortable country in a lot of ways. Very wealthy, in terms of its public infrastructure, very safe, especially for a place as urbanized as Japan, and extraordinarily convenient—I’ve never personally travelled to another place on this planet that offers more convenience at your fingertips for a middling price than Japan. You can get virtually anything you want twenty-four hours a day. So you have younger Japanese in cities like Tokyo and Osaka watching the television and seeing these older people waiting patiently in line for one bottle of water, toughing it out in these overcrowded shelters. People in their sixties and seventies eating their one bowl of rice per day and tucking under whatever scraps of clothing they can find to get through the night, the very cold nights up there, without heat. And I think that’s a powerful image for a lot of young Japanese who have grown up with convenience stores and twenty-four-hour internet cafes.

Back to Top

Author

Sam Stephenson is the author of Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project (Norton) and the director of the Jazz Loft Project at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. He is also writing a biography of Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

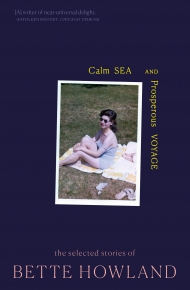

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.