Chaos Manor

• Sam Stephenson • October 1, 2013

821 Sixth Avenue was a hub for jazz musicians from 1954-1965, and many big names in New York found themselves there. The photographer W. Eugene Smith moved into the building in 1957 and eventually wired the place, intent on recording as much of the rehearsals, jam sessions, conversations, and daily life in the loft as possible. The result, though vast (40,000 photographs and 4,500 hours of audio recordings), accounted for a sliver of what was going on culturally, artistically, and politically in the city during the time. Explore a selection of significant spots on the map below.*

Chaos Manor, a multimedia theater installation based on Sam Stephenson's book The Jazz Loft Project, premieres this weekend, September 16 and 17, at The Invisible Dog.

*zoom out to see more locations (like the site of the 1964 World's Fair in far east Queens)

Malcolm X Interviews

92 Grove Street

At 92 Grove Street, Alex Haley rented a little studio in the back of the building. Starting in 1963, as Studio 360 tells it, “joining him in the 8 x 10 room for over 50 in-depth interviews in two years was another man—tall, bespectacled, with a goatee. Haley had already interviewed him for a couple of magazine profiles. Now he wanted to tell his whole life story—in a book.” This was Malcolm X, already known by the FBI for demanding black rights “by any means possible.” And though the Bureau had the studio “bugged,” Malcolm X insisted that he not be taped. “Dad was a fast typist,” says Bill Haley, his son. The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published in 1965.

In the spring of 1963, Gene Smith recorded The Negro and the American Promise from Channel 13, which featured interviews with Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and James Baldwin. In JLP Sam Stevenson quotes from Baldwin’s segment: “I don’t matter any longer what you do to me: you can put me in jail; you can kill me. By the time I was seventeen, you’d done everything you can do to me. The problem now is, How are you going to save yourselves?”

Norman Mailer Stabs His Wife 250 West 94th Street

“Norman Mailer, the writer, was arrested last night and accused of stabbing his wife, Adele. Mrs. Mailer, 37 years old, was in critical condition last night at University Hospital, Second Avenue and Twentieth Street. She was taken to the hospital at 8 o'clock Sunday morning with stab wounds in the abdomen and back. She apparently rode there in a private car. According to the police of the West 100th Street station, where the 37-year-old writer was being held, Mrs. Mailer told physicians at the hospital that she had fallen on glass in her apartment at 250 West 94th Street. The physicians were suspicious and notified the police.” (New York Times, November 22, 1960)

Cuban Missile Crisis Gaslight Café on MacDougal Street and West 3rd Street

October 23, 1962. “Twenty-one-year-old Bob Dylan was singing ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,’ “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and “No More Auction Block” at the Gaslight Café. ... But everything was overshadowed by the Cuban Missile Crisis. The threat of nuclear holocaust paralyzed the country. People were digging backyard bomb shelters and stockpiling canned food.” (Sam Stephenson, JLP)

Smith recorded the 11:00 news on WBAI radio that night, including commentary by Edward P. Morgan: “President Kennedy tonight signed the momentous proclamation ordering a selective blockade of Cuba.”

On the recently released Jacqueline Kennedy tapes, she recalls that time: "When President Kennedy learned of the failed invasion at Cuba's Bay of Pigs, less than three months into his presidency in 1961, he returned to the White House living quarters to weep, she said. ‘He came back over to the White House to his bedroom and he started to cry, just with me. You know, just for one — just put his head in his hands and sort of wept,’ she said. "It was so sad, because all his first hundred days and all his dreams, and then this awful thing to happen. And he cared so much.'" (ABC News)

Kenneth Koch writes to John Ashbery from 69 Perry Street

Dear Ashtray,

It’s really beginning to make me neurotic wondering why you don’t write, especially since my heart leaps up whenever I think of you and your little ways, as I did the other night and all NY seemed like a desert, an empty swimming pool without you, Coach John, Coach John Ashbery. In spite of all, though, while New York gapes starry-eyed with admiration at your handling of famous personages in Paris, I send you a 25$ check, hoping that you will be able to cash it. (This is for your half of Death Paints a Picture, a work which has been extravagantly admired by Robt Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and a few other lunatics). ... Jimmy Schuyler is going to dinner at the Motherwells. I said I didn’t much care for them. He said, “Oh but they’re wonderful together! She’s like an axe and he’s like a big hunk of raw meat.” Last Saturday night Bill de Kooning gave a birthday party for Ruth Kligman and many of our friends were there. Please send me some details of your manipulation of French celebrities, thank-you notes, conversations with authors, etc., of which there was only a slight hit at the party. …

Your fond “oncle d’Amerique

(reprinted in Painters & Poets, Tibor de Nagy Gallery)

This couple would have been Kenneth Koch’s neighbors.

Max’s Kansas City 213 Park Avenue South

Gene Smith moved out of 821 Sixth Avenue in 1965, the same year that Max’s Kansas City opened. The restaurant was a microcosmic hub for artists, musicians, designers, and celebrities of Manhattan’s nightlife. Max’s proprietor, Mickey Ruskin, was an enthusiastic, if unconventional, patron of the arts; he turned his restaurant into a performance venue, creative forum, and informal gallery space. A minor character, Brigitte Angel, wrote in her memoir, From Vienna to 14th Street, that Ruskin systematically arranged the restaurant with artists up front, many of them running up tabs that many couldn’t pay off (“instead, Mickey let them barter their drinks in exchange for paintings”); in the back room the people who were “way out” were admitted (“Andy Warhol and other celebrities frequented that room, usually late at night”).

The Village Vanguard 178 Seventh Avenue South

After nearly twenty years of showcasing folk musicians and beat poets, the Village Vanguard solidified its identity as a jazz club in 1957. The first of the Vanguard’s famous live recordings was made by Sonny Rollins on November 3 that year. In 1961, The Bill Evans Trio recorded two classic live jazz albums at the Vanguard: Sunday at the Village Vanguard, and Waltz for Debby. Sam writes in JLP of Jim Hall and Jimmy Raney recalling a gig at the Vanguard during which their wives took photos of band. Later, at 821 Sixth Avenue, they implored Eugene Smith to help them develop the film. “He took us into his darkroom and treated our film like it was his. You’d have thought he was making pictures for Life,” says Hall.

Hector's Cafeteria 1627 Broadway at West 50th Street

In the opening pages of Jack Kerouac's On the Road, Dean Moriarty arrives in New York for the first time: “They got off the Greyhound bus at 50th Street and cut around the corner looking for a place to eat and went right in Hector’s, and since then, Hector's Cafeteria has always been a big symbol of New York for Dean." That said, there were apparently four cafeterias dubbed Hector’s in Times Square. The allure of places like Hector’s is quickly demystified by Willem de Kooning when he talks about The Club: “We just wanted to get a loft, instead of sitting in those goddamned cafeterias.” (de Kooning: An American Master, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan)

The Factory 231 East 47th Street

Andy Warhol moved into the loft (quickly dubbed The Factory) in late 1963. Danny Fields, in Jean Stein’s Edie: An American Biography, describes the vibe: “A coin wall telephone by the door; it was extremely important: there’d always be a line of desperate people, calling in or out. The Factory was totally open; anybody could walk in. At one point hey put up a sign, DO NOT ENTER UNLESS YOU ARE EXPECTED, which everyone ignored.” 821 Sixth Avenue procured a vibe of its own. Sam writes in JLP, “Jazz—like most great art going back to antiquity—needed benefactors. Lofts like 821 Sixth Avenue served that purpose. There was some artistic freedom and camaraderie and some dope to be smoked. The loft was where you went when you had no gigs. It was here you went after your gigs, where you could play whatever you wanted to play without a club owner complaining. But you had to be good.”

The Club 39 East 8th Street, between University and Greene

In 1949, Franz Kline paid a New Zealander he met at the Cedar Tavern $250 in “key money” to take a lease on the loft that “would become a mirror of the promise and predicaments of American art.” The two “rules” were these: first, no women, Communists, or homosexuals; second, any two established members had the ability to make it extremely difficult for hopeful applicants to be accepted. The first rule was largely disputed and eventually faltered. (de Kooning: An American Master, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan)

The Club became a hangout for the abstract expressionists, including Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Conrad Marca-Reilli, Ad Reinhardt, Joop Sanders, Elaine de Kooning and many others, until it closed in 1962.

As Robert Motherwell described it: “The Club really began just about the time I became a professor at Hunter and was married with a child and had more children and had to live a regular life. The essential nature of the Club was for bachelors, for guys to get together - although that's not a fair way to put it. But if you're carrying on a complete life and having to keep regular hours, which I used to have to, then to go out in the evening for six hours and drink and talk was less reasonable than it was before...” (Smithsonian Archives of American Art)

The 1964 World’s Fair Flushing Meadows Park

In the summer of 1964, the Merry Pranksters, a group of people who congregated around author Ken Kesey, took a road trip in their revamped school bus nicknamed “Further.” The road trip culminated at the World’s Fair, which the psychedelic drug promoters considered “groovy." The reality of the fair was much darker: “In 1964, the fair produced nothing but sinister urban legends in unsettling numbers, grisly stories of abduction, murder, and cover-ups. Children were said to have disappeared. Body parts were allegedly concealed in the sleek aluminum spheres and silos.” (Robert Stone, “The Prince of Possibility,” The New Yorker)

Writes Sam: “[Jimmy] Stevenson had a regular gig at The Apartment, a supper club on the east side of Manhattan, with Ray Starling on piano and Al Beldini on drums. This trio also performed at a temporary jazz club on the grounds of the World’s Fair.”

John Wray wrote about the Home of Tomorrow at the 1964 World’s Fair in his “Impossible Sightseeing Tour of New York City” in Issue 8.

Village Gate 158 Bleecker Street

Art D’Lugoff, the owner of this downtown nightclub, had a reputation for timely bookings. When Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger were blacklisted in the 1950s, D’Lugoff booked them; he hired Lenny Bruce in the 1960s when he knew policemen would be in the audience, waiting for an excuse to arrest the comedian. Nina Simone performed there in the summer of 1964. Joe Hagan wrote about it in the Believer: “It was after midnight and the compact and muscular woman radiated anger following a performance at the smoke-filled Village Gate in New York City. ‘She was scary, for sure,’ recounts playwright Sam Shepard, who during the summer of 1964 was a twenty-one-year-old busboy tasked with delivering ice to chill Simone’s champagne. Only moments before, her long fingers arched over a black Steinway, Simone held the audience rapt, even terrified. ‘Mississippi Goddam,’ her first bona fide protest song, had caused ripples across the country, especially in the South, which was roiling with racial unrest.”

As the months of racial violence played out, the music from the jazz scene around New York moved into deeper and deeper abstraction, and the jam sessions at 821 Sixth Avenue reflected the change.

Bassist Vinnie Burke : Well, this is a bad time, a bad time in history. It’s like Lincoln repeating itself. When Lincoln was killed they said the atmosphere is almost identical. Scott: Yeah, shit. It’s like, you know, now we’re only more neurotic, I believe, because we’re more progressive. It’s almost like a button can blow the whole thing up, you know. Sims: Yeah, but you can’t stop living, man. For a lot of big stars today - Miles included, and Mulligan, and Monk - I think the worse the times are, the more they play, though. So we ought to start playing again. A few minutes later, Sims: Let’s blow one. (JLP Timeline)

Back to Top

Author

Sam Stephenson is the author of Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project (Norton) and the director of the Jazz Loft Project at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. He is also writing a biography of Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

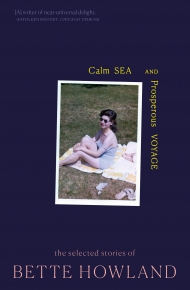

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.