Elizabeth McCracken | Annie Dillard

#APStogether • July 20, 2020

Read and discuss The Maytrees by Annie Dillard with Elizabeth McCracken and A Public Space. Starting July 23, the second in #APStogether, a series of free virtual book clubs that take place on social media under the hashtag #APStogether.

Join us for a virtual discussion of The Maytrees with Elizabeth McCracken on Tuesday, August 4. Register here.

Like all of my favorite books, The Maytrees is hard to describe: its plot is time, really, but it's about empathy and marriage and divorce and love and the consolations of art. It begins with the courtship of Lou Bigelow and Toby Maytree, who marry and move to Provincetown and become the eponymous Maytrees (other Maytrees follow) and it's full of remarkable characters and remarkable sentences. Some slim novels are spare and clean (I love those, too) but The Maytrees is crammed full, like an old New England house filled with geegaws and books and bricabrac. Above all, it is an intensely beautiful book.

—Elizabeth McCracken on The Maytrees

Reading Schedule

Day 1 | July 23: Prologue & Preface to page 9 (through "She was outside his reach.")

Day 2 | July 24: Pages 11-29 (through "The more she saw of the Provincetown school, the more she favored grisailles.")

Day 3 | July 25: Pages 31-43 (through "Maytree was tall, and Sooner was strong as Babe Ruth.")

Day 4 | July 26: Pages 45-59 (through "Perhaps, she asked later, he never did?")

Day 5 | July 27: Start of Part I, pages 61-74 (through "Goodnight, Lou.")

Day 6 | July 28: Pages 75-89 (through "She should have lashed her elbows and knees, like Aletus.")

Day 7 | July 29: Pages 91-103 (including “interlude," through "Or was she of this earth, earthy?")

Day 8 | July 30: Pages 105-119 (through "An unfair sample.")

Day 9 | July 31: Pages 121-133 ("In the meantime she cleared the landing strip.")

Day 10 | August 1: Start of Part II, pages 135-152 (through "He fell asleep.")

Day 11 | August 2: Pages 153-171 (through "Do you believe it?")

Day 12 | August 3: Start of Part III, pages 173-198 (through "Her inquiry was: What did she hope?")

Day 13 | August 4: Pages 199-216 (The End)

Click here for more information on how it works.

Day 1 | July 23

Reading: Prologue & Preface to page 9 (through "She was outside his reach.")

Ordinarily I dislike prologues, especially ones that dispense geological & historic information. Just start the book! But the first sentence, in its simplicity & mystery, softens my heart & makes me listen. —Elizabeth

Verbs are descriptive language, too. Dillard’s are wonderful: boarded, flopped. —Elizabeth

Who is asking this question, & of whom? —Elizabeth

I always tell my students that a 3rd person narrator is (as I once heard God described) “a gaseous invertebrate.” Every gas has different properties; some can permeate any border & some only select; some 3rd person narrators can have opinions. —Elizabeth

Interestingly, my hardcover edition doesn’t include the word preface on page 7, but my paperback does. What subtle difference was Dillard going for? What, in fiction, is the difference between a preface & a prologue? —Elizabeth

The physical descriptions of characters verge on the surreal, the spiritual. —Elizabeth

An audacious double allusion to Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Calloway’s “Minnie the Moocher.” —Elizabeth

Day 2 | July 24

Reading: Pages 11-29 (through "The more she saw of the Provincetown school, the more she favored grisailles.")

A relief to shift into Lou’s head at the top of page 11. I believe utterly in Maytree, but I find—as Lou herself does—that he takes up a lot of the oxygen. —Elizabeth

The way Dillard describes the physicality of her characters is strange & wonderful. She’s as interested in physical description as Dickens, though she does it in the opposite way: not encyclopedic, but a whole soul impressionistic portrait. —Elizabeth

If ever somebody tells you that all adverbs are bad, please show them this use of “mysteriously.” —Elizabeth

Dillard knows her characters so well the smallest moments characterize: Maytree keeping an eye on the poison ivy while showing off, Lou mocking him but only in her head, “as if bored” but not actually bored. —Elizabeth

Anyone who has ever walked through the dunes to a dune shack has wondered this. Dillard never forgets the physical tragic slapstick comedy of the human body.

On page 18, there’s a double space & we land in Lou’s past. Time is odd in this book, but I would follow Dillard anywhere. —Elizabeth

Annie Dillard loves love, wondering & writing about it; Lou wondering she would rather have love intact, or to love perfectly, resounds through the entire book. —Elizabeth

Of course the concertina-playing Primo Dial runs away for “winsome twins who played glockenspiels.” No other instruments would work so well; I can see the foul trio, making music & also whoopee. —Elizabeth

Dillard is a beloved writing teacher, & I take the parenthetical aside on page 22 about Maytree’s fear of clarity as a fond, chiding note to her students as well as possibly her own younger self. —Elizabeth

In one sentence: the pleasure of seeing the conical cups, the pleasure of the word “conical,” the pleasure of knowing this little prankish sadistic part of Deary’s personality. —Elizabeth

It is taking all my will power not to just point out Dillard’s weird & perfect verbs. Here’s two in one phrase. “…amber drop earrings that suggested her ears were draining.” —Elizabeth

I like to think, & it isn’t impossible, that the joke about Reevadare’s name is also an allusion to Alexander Chee, a student of Dillard’s. —Elizabeth

Cornelius toasting with the Santayana quote—“If pain could have saved us, we should long ago have been saved”—is pretty close to the bone in 2020. —Elizabeth

Time in The Maytrees is a lot like the dunes, shifting & palpable. When Dillard lists all of Deary’s marriages, we learn about her but we also fly through time, to catch us up with Deary’s love life. —Elizabeth

Day 3 | July 25

Reading: Pages 31-43 (through "Maytree was tall, and Sooner was strong as Babe Ruth.")

Dillard knows you know the antecedents to these pronouns. —Elizabeth

This whole small chapter, after their marriage, is so full of oddity & love. I don’t know what Dillard thinks about scene, except that it’s idiosyncratic, but this is immediate & intimate. —Elizabeth

Also, Dillard loves beds. Anyone who lives in a seaside town is preoccupied with sleeping arrangements: carnal beds, spare beds, sick beds, cribs & cots. “Where will that person sleep?” is one of the most pressing questions in human life. —Elizabeth

I love Maytree’s packing list for his shack: Yeats, nails, hardboiled eggs, Lawrence, &c. —Elizabeth

The images that characters themselves think up tell us things about the characters they might rather have kept secret. —Elizabeth

Day 4 | July 26

Reading: Pages 45-59 (through "Perhaps, she asked later, he never did?")

The 3rd person narrator, when it comes to Maytree (I never think of him as Toby) is so subtle. On page 45, he asks Lou a question, & she agrees—only with her smile & eyes. He has an enormous ego which Dillard gets at from the inside. —Elizabeth

The stars are always over the Maytrees, the puzzle of their constancy even as they move. In an interview with Publishers Weekly Dillard says she wanted to call the book a "Romantic Comedy about Light Pollution." To remove the stars for any reason is a crime. —Elizabeth

Here is the interview, in which she reveals that this slender book was once 1400 pages. —Elizabeth

“But the story wouldn't bear it; it's a simple little story. You can't pile all this stuff on the back of a frail couple.” —Annie Dillard on the Maytrees.

“I'd look at each character: do you have to be here? Are you necessary or optional? If you're optional, then off with your head!” —Annie Dillard on the Maytrees.

Maytree is always most insufferable when we are in his head & know his thoughts. This is Dillard’s empathetic ruthlessness. Or maybe all poets make surprise visits to their publishers? —Elizabeth

Though we don’t know it, when we turn to page 61, we will learn that for all of these pages, we have not yet started Part One of the book. So where have we been? In various states of before-time. —Elizabeth

Day 5 | July 27

Reading: Start of Part I, pages 61-74 (through "Goodnight, Lou.")

Part One begins with an accident: Petie, broken in Maytree’s arms, the start of a lot of broken things. —Elizabeth

We’re in Petie’s head here—sudden & yet we understand. Dillard lets her dialogue clang against what we already know about the characters’ interiors. —Elizabeth

As things unravel Dillard pays attention to bodies: Lou holds Maytree; he tells her he will always love her; she steps away instantly. On the next page he doesn’t know how to stand. It’s heartbreaking. —Elizabeth

The oystermen who drown as the tide comes: a haunting image, & a haunting thought, that your everyday life might kill you as you bootlessly shout for help. Strange death in the landscape permeates the book (think of the murdered Woman in the Dunes). —Elizabeth

Lou’s own wish—to love instead of being loved—reappears, horribly, in Maytree’s head. Her love for him created a fata morgana, & now he believes that he only believed he loved her back. —Elizabeth

Day 6 | July 28

Reading: Pages 75-89 (through "She should have lashed her elbows and knees, like Aletus.")

And now we step back in time, & in Maytree’s own head hear of his love for Deary, to whom he’s bound, & his regret. Dillard’s subject is love: she knows how often human beings screw it up. —Elizabeth

Every writer has at least one part of the human anatomy they’re partial to. Dillard’s is ears. —Elizabeth

The passage where Dillard leaps ahead to Lou’s old age & death is my favorite. I think of Dillard saying she took out everything that wasn’t necessary, & the fact of the ashes on the pilot’s bookshelf. Yes: necessary. —Elizabeth

Just putting this here: Jane Cairo is not sure she wants to get used to Henry James, who Maytree has “put her on.” —Elizabeth

Lou listing possible last things would be beautiful if we hadn’t just read about the last time she was seen, and her death; knowing her end, it’s both wrenching & full of light. —Elizabeth

Day 7 | July 29

Reading: Pages 91-103 (including “interlude," through "Or was she of this earth, earthy?")

I myself climbed the Pilgrim Monument every day for a while as a form of contemplation in the early 90s. I’m not so good or thoughtful as Lou, but it’s an excellent monument. —Elizabeth

Dillard likes asides, & on page 93, there’s a killer: “as it happened, while she was washing around Deary’s deepest and most noisome bedsore.” Another startling jump forward. —Elizabeth

The description of how Pete thinks, which tries to both anatomize and embody his thought process, is difficult and thrilling. It’s not just virtuosity of language, but tied completely to both character & plot. —Elizabeth

Here’s an interlude. From what? Where do we resume? I do not know. The book has a nominal exoskeleton that confounds me, frankly. —Elizabeth

Who among us has not felt this way? & regard that adverb, which changes everything. There’s a whole biography in that “probably.” —Elizabeth

Day 8 | July 30

Reading: Pages 105-119 (through "An unfair sample.")

Is there a more chilling detail of a loving marriage than one spouse annotating the other’s letters? No offense to those of you posed with your beloveds in your avatars, but: brrrrr. —Elizabeth

Dillard’s ability to describe Lou’s paintings is painterly itself, built up with in brushstrokes—both word choice & image—& color that shouldn’t work but does. —Elizabeth

“Scumble” is fantastic word. I always associate it with the splendid Antoine Wilson. —Elizabeth

The description of all the Petes seated at the table is strange & beautiful. When I first read The Maytrees, my son Gus, now 13, was an infant, & I imagined I might feel like this. (I don’t.) —Elizabeth

Deary arrives in this book as a hoyden in the dunes; we learn that she has a distinguished education; she becomes a Maytree & a lady & a working architect & a clothes horse. Dillard knows that human beings are complicated stories. —Elizabeth

Day 9 | July 31

Reading: Pages 121-133 ("In the meantime she cleared the landing strip.")

Time is one of Dillard’s topics, but how it changes us & how it doesn’t, what’s bound to erode & what’s utterly insoluble. —Elizabeth

Dillard’s metaphoric language is often very funny—the baby Tandy the size and shape of a one-quart thermos--& odd & lovely—love rebounding from Maine to Mass. off “that old blackboard the moon.” It shows things & undermines them, both. —Elizabeth

Day 10 | August 1

Reading: Start of Part II, pages 135-152 (through "He fell asleep.")

Of all the obscure words Dillard deploys, tatterdemalion is perhaps my favorite, & wonderfully used in this four word sentence. Beautiful, surprising: extravagance set in simplicity. —Elizabeth

Pete, too, meditates on what old age means, what love means, and assumes he knows his parents’ past, that they had never loved each other. Would it be better or worse for him to know the truth? —Elizabeth

Maytree & Deary’s life turns out to have been a balancing act, now that caretaker Maytree cannot take care. But he has money, & in Provincetown, “his real wife.” He knows he’s lucky though he doesn’t feel it. —Elizabeth

Day 11 | August 2

Reading: Pages 153-171 (through "Do you believe it?")

Lovely to see a mention of Mary Heaton Vorse here, author of Time and the Town, which could be the title for this book, too. Her house in Provincetown has just been turned into an art center. —Elizabeth

From a 1942 NYTimes article: “WHEN Mary Heaton Vorse had lived for thirty-five years in Provincetown a village neighbor said, ‘We've gotten to think of you as one of us.’ And she could appreciate the compliment of that acceptance, after long novitiate.”

(“After long novitiate” strikes me as a Maytreesian phrase. —Elizabeth)

Maytree, walking to the shack, thinks of the dog as otherworldly, when it is an ambassador from the actual world—to Maytree ‘otherworldly’ means something Maytree himself has not thought up. Such tension in this walk, because we know who he is walking to, & she herself is innocent. —Elizabeth

The reunion of The Maytrees, of who at least I initially believed were the eponymous Maytrees, is quiet & fraught & funny. Lord love a duck! —Elizabeth

Day 12 | August 3

Reading: Start of Part III, pages 173-198 (through "Her inquiry was: What did she hope?")

Deary, with her yellow & blue hands, her jewelry, her Harris tweed, is the most physically vivid character in the book. She is a Love Object. —Elizabeth

This triptych of sentences, the question in the middle, the flanking phrases with their semicolons, wrecks me. —Elizabeth

“She had expensive new teeth and looked like Burt Lancaster.” Never forget that Annie Dillard is laugh-out-loud funny. —Elizabeth

And of course, as with the death of Deary, she juggles the numinous & the workaday world, the ordinary & the idiosyncratic, like nobody else. I rarely cry while reading fiction but this does it for me. —Elizabeth

The reason, probably, why Maytree doesn’t want Pete to go to sea. The specter of the Peaked Hill Bars shows up early in the book, but in Lou’s POV. —Elizabeth

Lou is a quiet person; Maytree continually sees her silence as a receptacle, not a bulwark. —Elizabeth

I love the unapologetically New England & very apt & disgusting use of “jimmies” here. —Elizabeth

Day 13 | August 4

Reading: Pages 199-216 (The End)

Suddenly, an epigraph, & this time I think the antecedents to these pronouns are purposefully unclear, though we can hope we know. —Elizabeth

Lou’s triumph. Is this a renunciation of romantic love or a redefinition?—Elizabeth

I find Maytree lovable but not likeable (like some other of men of his generation I have known). —Elizabeth

Any time you visit a beloved place after an absence of decades, you are a time traveler suddenly in the incomprehensible future: Lou treats Maytree’s shock & judgment & squeamishness with a drag show. —Elizabeth

& yet he himself loves scandalizing the neighbors, throwing off convention. When we dismiss convention, we always pick & choose: some conventions are invisibly dear to us. That may be one of the messages of The Maytrees. —Elizabeth

Dillard loves the natural world, but the fabricated world is always running through it, “like a brochette” (like Reevadare & her husbands.) —Elizabeth

We get Deary’s beautiful death, & now Maytree’s. Lou’s death is last chronologically, but first in the book, chapters & chapters ago. —Elizabeth

The Maytrees ends with some of the most astonishing prose I have ever read. I have no other gloss or comment on it, at least right now. —Elizabeth

Join us for a virtual discussion of The Maytrees with Elizabeth McCracken on Tuesday, August 4. Register here.

Like all of my favorite books, The Maytrees is hard to describe: its plot is time, really, but it's about empathy and marriage and divorce and love and the consolations of art. It begins with the courtship of Lou Bigelow and Toby Maytree, who marry and move to Provincetown and become the eponymous Maytrees (other Maytrees follow) and it's full of remarkable characters and remarkable sentences. Some slim novels are spare and clean (I love those, too) but The Maytrees is crammed full, like an old New England house filled with geegaws and books and bricabrac. Above all, it is an intensely beautiful book.

—Elizabeth McCracken on The Maytrees

Reading Schedule

Day 1 | July 23: Prologue & Preface to page 9 (through "She was outside his reach.")

Day 2 | July 24: Pages 11-29 (through "The more she saw of the Provincetown school, the more she favored grisailles.")

Day 3 | July 25: Pages 31-43 (through "Maytree was tall, and Sooner was strong as Babe Ruth.")

Day 4 | July 26: Pages 45-59 (through "Perhaps, she asked later, he never did?")

Day 5 | July 27: Start of Part I, pages 61-74 (through "Goodnight, Lou.")

Day 6 | July 28: Pages 75-89 (through "She should have lashed her elbows and knees, like Aletus.")

Day 7 | July 29: Pages 91-103 (including “interlude," through "Or was she of this earth, earthy?")

Day 8 | July 30: Pages 105-119 (through "An unfair sample.")

Day 9 | July 31: Pages 121-133 ("In the meantime she cleared the landing strip.")

Day 10 | August 1: Start of Part II, pages 135-152 (through "He fell asleep.")

Day 11 | August 2: Pages 153-171 (through "Do you believe it?")

Day 12 | August 3: Start of Part III, pages 173-198 (through "Her inquiry was: What did she hope?")

Day 13 | August 4: Pages 199-216 (The End)

Click here for more information on how it works.

Day 1 | July 23

Reading: Prologue & Preface to page 9 (through "She was outside his reach.")

Ordinarily I dislike prologues, especially ones that dispense geological & historic information. Just start the book! But the first sentence, in its simplicity & mystery, softens my heart & makes me listen. —Elizabeth

Verbs are descriptive language, too. Dillard’s are wonderful: boarded, flopped. —Elizabeth

“Twice a day behind their house the tide boarded the sand. Four times a year the seasons flopped over.”

Who is asking this question, & of whom? —Elizabeth

“Why not memorize everything, just in case?”

I always tell my students that a 3rd person narrator is (as I once heard God described) “a gaseous invertebrate.” Every gas has different properties; some can permeate any border & some only select; some 3rd person narrators can have opinions. —Elizabeth

Interestingly, my hardcover edition doesn’t include the word preface on page 7, but my paperback does. What subtle difference was Dillard going for? What, in fiction, is the difference between a preface & a prologue? —Elizabeth

The physical descriptions of characters verge on the surreal, the spiritual. —Elizabeth

“He felt himself blush and knew his freckles looked green. She was young and broad of mouth and eye and jaw, fresh, solid and airy, as if light rays worked her instead of muscles.”

An audacious double allusion to Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Calloway’s “Minnie the Moocher.” —Elizabeth

“Lou Bigelow’s candid glance, however, contained neither answer nor question, only a spreading pleasure, like Blake’s infant joy, kicking the gong around.”

Day 2 | July 24

Reading: Pages 11-29 (through "The more she saw of the Provincetown school, the more she favored grisailles.")

A relief to shift into Lou’s head at the top of page 11. I believe utterly in Maytree, but I find—as Lou herself does—that he takes up a lot of the oxygen. —Elizabeth

The way Dillard describes the physicality of her characters is strange & wonderful. She’s as interested in physical description as Dickens, though she does it in the opposite way: not encyclopedic, but a whole soul impressionistic portrait. —Elizabeth

If ever somebody tells you that all adverbs are bad, please show them this use of “mysteriously.” —Elizabeth

“Mysteriously, some years ago she earned the first degree MIT awarded a female in architecture.”

Dillard knows her characters so well the smallest moments characterize: Maytree keeping an eye on the poison ivy while showing off, Lou mocking him but only in her head, “as if bored” but not actually bored. —Elizabeth

“In her mind she replied, as if bored, Oh can you.”

Anyone who has ever walked through the dunes to a dune shack has wondered this. Dillard never forgets the physical tragic slapstick comedy of the human body.

“Lou knew it would have an outhouse. But where.”

On page 18, there’s a double space & we land in Lou’s past. Time is odd in this book, but I would follow Dillard anywhere. —Elizabeth

Annie Dillard loves love, wondering & writing about it; Lou wondering she would rather have love intact, or to love perfectly, resounds through the entire book. —Elizabeth

Of course the concertina-playing Primo Dial runs away for “winsome twins who played glockenspiels.” No other instruments would work so well; I can see the foul trio, making music & also whoopee. —Elizabeth

Dillard is a beloved writing teacher, & I take the parenthetical aside on page 22 about Maytree’s fear of clarity as a fond, chiding note to her students as well as possibly her own younger self. —Elizabeth

In one sentence: the pleasure of seeing the conical cups, the pleasure of the word “conical,” the pleasure of knowing this little prankish sadistic part of Deary’s personality. —Elizabeth

“She handed out conical Dixie cups no one could set down.”

It is taking all my will power not to just point out Dillard’s weird & perfect verbs. Here’s two in one phrase. “…amber drop earrings that suggested her ears were draining.” —Elizabeth

I like to think, & it isn’t impossible, that the joke about Reevadare’s name is also an allusion to Alexander Chee, a student of Dillard’s. —Elizabeth

Cornelius toasting with the Santayana quote—“If pain could have saved us, we should long ago have been saved”—is pretty close to the bone in 2020. —Elizabeth

Time in The Maytrees is a lot like the dunes, shifting & palpable. When Dillard lists all of Deary’s marriages, we learn about her but we also fly through time, to catch us up with Deary’s love life. —Elizabeth

Day 3 | July 25

Reading: Pages 31-43 (through "Maytree was tall, and Sooner was strong as Babe Ruth.")

Dillard knows you know the antecedents to these pronouns. —Elizabeth

“After they married she learned to feel their skin as double-sided. They felt a pause.”

This whole small chapter, after their marriage, is so full of oddity & love. I don’t know what Dillard thinks about scene, except that it’s idiosyncratic, but this is immediate & intimate. —Elizabeth

Also, Dillard loves beds. Anyone who lives in a seaside town is preoccupied with sleeping arrangements: carnal beds, spare beds, sick beds, cribs & cots. “Where will that person sleep?” is one of the most pressing questions in human life. —Elizabeth

I love Maytree’s packing list for his shack: Yeats, nails, hardboiled eggs, Lawrence, &c. —Elizabeth

The images that characters themselves think up tell us things about the characters they might rather have kept secret. —Elizabeth

“Her felt he saw through Lou’s eyes as an Aztec priest, having flayed an enemy, donned the skin. Or somewhat less so.”

Day 4 | July 26

Reading: Pages 45-59 (through "Perhaps, she asked later, he never did?")

The 3rd person narrator, when it comes to Maytree (I never think of him as Toby) is so subtle. On page 45, he asks Lou a question, & she agrees—only with her smile & eyes. He has an enormous ego which Dillard gets at from the inside. —Elizabeth

The stars are always over the Maytrees, the puzzle of their constancy even as they move. In an interview with Publishers Weekly Dillard says she wanted to call the book a "Romantic Comedy about Light Pollution." To remove the stars for any reason is a crime. —Elizabeth

Here is the interview, in which she reveals that this slender book was once 1400 pages. —Elizabeth

“But the story wouldn't bear it; it's a simple little story. You can't pile all this stuff on the back of a frail couple.” —Annie Dillard on the Maytrees.

“I'd look at each character: do you have to be here? Are you necessary or optional? If you're optional, then off with your head!” —Annie Dillard on the Maytrees.

Maytree is always most insufferable when we are in his head & know his thoughts. This is Dillard’s empathetic ruthlessness. Or maybe all poets make surprise visits to their publishers? —Elizabeth

Though we don’t know it, when we turn to page 61, we will learn that for all of these pages, we have not yet started Part One of the book. So where have we been? In various states of before-time. —Elizabeth

“Perhaps, she asked later, he never did."

Day 5 | July 27

Reading: Start of Part I, pages 61-74 (through "Goodnight, Lou.")

Part One begins with an accident: Petie, broken in Maytree’s arms, the start of a lot of broken things. —Elizabeth

We’re in Petie’s head here—sudden & yet we understand. Dillard lets her dialogue clang against what we already know about the characters’ interiors. —Elizabeth

“Brandy all around?”

As things unravel Dillard pays attention to bodies: Lou holds Maytree; he tells her he will always love her; she steps away instantly. On the next page he doesn’t know how to stand. It’s heartbreaking. —Elizabeth

The oystermen who drown as the tide comes: a haunting image, & a haunting thought, that your everyday life might kill you as you bootlessly shout for help. Strange death in the landscape permeates the book (think of the murdered Woman in the Dunes). —Elizabeth

Lou’s own wish—to love instead of being loved—reappears, horribly, in Maytree’s head. Her love for him created a fata morgana, & now he believes that he only believed he loved her back. —Elizabeth

“He never really loved Lou. He saw that now.”

Day 6 | July 28

Reading: Pages 75-89 (through "She should have lashed her elbows and knees, like Aletus.")

And now we step back in time, & in Maytree’s own head hear of his love for Deary, to whom he’s bound, & his regret. Dillard’s subject is love: she knows how often human beings screw it up. —Elizabeth

Every writer has at least one part of the human anatomy they’re partial to. Dillard’s is ears. —Elizabeth

“Her ears were soft as Petie’s, flat to the head.”

The passage where Dillard leaps ahead to Lou’s old age & death is my favorite. I think of Dillard saying she took out everything that wasn’t necessary, & the fact of the ashes on the pilot’s bookshelf. Yes: necessary. —Elizabeth

Just putting this here: Jane Cairo is not sure she wants to get used to Henry James, who Maytree has “put her on.” —Elizabeth

“—You’ll get used to James, he told her. —Not sure I want to.”

Lou listing possible last things would be beautiful if we hadn’t just read about the last time she was seen, and her death; knowing her end, it’s both wrenching & full of light. —Elizabeth

Day 7 | July 29

Reading: Pages 91-103 (including “interlude," through "Or was she of this earth, earthy?")

I myself climbed the Pilgrim Monument every day for a while as a form of contemplation in the early 90s. I’m not so good or thoughtful as Lou, but it’s an excellent monument. —Elizabeth

Dillard likes asides, & on page 93, there’s a killer: “as it happened, while she was washing around Deary’s deepest and most noisome bedsore.” Another startling jump forward. —Elizabeth

The description of how Pete thinks, which tries to both anatomize and embody his thought process, is difficult and thrilling. It’s not just virtuosity of language, but tied completely to both character & plot. —Elizabeth

Here’s an interlude. From what? Where do we resume? I do not know. The book has a nominal exoskeleton that confounds me, frankly. —Elizabeth

Who among us has not felt this way? & regard that adverb, which changes everything. There’s a whole biography in that “probably.” —Elizabeth

“He had chosen his own disgrace. He would probably do it again.”

Day 8 | July 30

Reading: Pages 105-119 (through "An unfair sample.")

Is there a more chilling detail of a loving marriage than one spouse annotating the other’s letters? No offense to those of you posed with your beloveds in your avatars, but: brrrrr. —Elizabeth

Dillard’s ability to describe Lou’s paintings is painterly itself, built up with in brushstrokes—both word choice & image—& color that shouldn’t work but does. —Elizabeth

“Scumble” is fantastic word. I always associate it with the splendid Antoine Wilson. —Elizabeth

The description of all the Petes seated at the table is strange & beautiful. When I first read The Maytrees, my son Gus, now 13, was an infant, & I imagined I might feel like this. (I don’t.) —Elizabeth

“That is who she missed, those boys now overwritten.”

Deary arrives in this book as a hoyden in the dunes; we learn that she has a distinguished education; she becomes a Maytree & a lady & a working architect & a clothes horse. Dillard knows that human beings are complicated stories. —Elizabeth

Day 9 | July 31

Reading: Pages 121-133 ("In the meantime she cleared the landing strip.")

Time is one of Dillard’s topics, but how it changes us & how it doesn’t, what’s bound to erode & what’s utterly insoluble. —Elizabeth

“Old people were not incredulous at having once been young, but at being young for so many decades running.”

Dillard’s metaphoric language is often very funny—the baby Tandy the size and shape of a one-quart thermos--& odd & lovely—love rebounding from Maine to Mass. off “that old blackboard the moon.” It shows things & undermines them, both. —Elizabeth

Day 10 | August 1

Reading: Start of Part II, pages 135-152 (through "He fell asleep.")

Of all the obscure words Dillard deploys, tatterdemalion is perhaps my favorite, & wonderfully used in this four word sentence. Beautiful, surprising: extravagance set in simplicity. —Elizabeth

“He remembered her tatterdemalion.”

Pete, too, meditates on what old age means, what love means, and assumes he knows his parents’ past, that they had never loved each other. Would it be better or worse for him to know the truth? —Elizabeth

Maytree & Deary’s life turns out to have been a balancing act, now that caretaker Maytree cannot take care. But he has money, & in Provincetown, “his real wife.” He knows he’s lucky though he doesn’t feel it. —Elizabeth

Day 11 | August 2

Reading: Pages 153-171 (through "Do you believe it?")

Lovely to see a mention of Mary Heaton Vorse here, author of Time and the Town, which could be the title for this book, too. Her house in Provincetown has just been turned into an art center. —Elizabeth

From a 1942 NYTimes article: “WHEN Mary Heaton Vorse had lived for thirty-five years in Provincetown a village neighbor said, ‘We've gotten to think of you as one of us.’ And she could appreciate the compliment of that acceptance, after long novitiate.”

(“After long novitiate” strikes me as a Maytreesian phrase. —Elizabeth)

Maytree, walking to the shack, thinks of the dog as otherworldly, when it is an ambassador from the actual world—to Maytree ‘otherworldly’ means something Maytree himself has not thought up. Such tension in this walk, because we know who he is walking to, & she herself is innocent. —Elizabeth

The reunion of The Maytrees, of who at least I initially believed were the eponymous Maytrees, is quiet & fraught & funny. Lord love a duck! —Elizabeth

“—Maytree, she started again, and smiled. Good to see you. He was the one who used to overdo things.”

Day 12 | August 3

Reading: Start of Part III, pages 173-198 (through "Her inquiry was: What did she hope?")

Deary, with her yellow & blue hands, her jewelry, her Harris tweed, is the most physically vivid character in the book. She is a Love Object. —Elizabeth

This triptych of sentences, the question in the middle, the flanking phrases with their semicolons, wrecks me. —Elizabeth

“It was that chrome winter day’s last light; the smoke of sea-frost blurred the horizon. Did Deary eat? Barely; applesauce.”

“She had expensive new teeth and looked like Burt Lancaster.” Never forget that Annie Dillard is laugh-out-loud funny. —Elizabeth

And of course, as with the death of Deary, she juggles the numinous & the workaday world, the ordinary & the idiosyncratic, like nobody else. I rarely cry while reading fiction but this does it for me. —Elizabeth

The reason, probably, why Maytree doesn’t want Pete to go to sea. The specter of the Peaked Hill Bars shows up early in the book, but in Lou’s POV. —Elizabeth

“Damn, he thought—not that he would watch his neighbors drown, but that it was part of life.”

Lou is a quiet person; Maytree continually sees her silence as a receptacle, not a bulwark. —Elizabeth

“Still in her twenties, she spoke three languages and held her tongue in all of them.”

I love the unapologetically New England & very apt & disgusting use of “jimmies” here. —Elizabeth

“They found mouse poops like jimmies and nests of shredded newspaper.”

Day 13 | August 4

Reading: Pages 199-216 (The End)

Suddenly, an epigraph, & this time I think the antecedents to these pronouns are purposefully unclear, though we can hope we know. —Elizabeth

Lou’s triumph. Is this a renunciation of romantic love or a redefinition?—Elizabeth

“She had once tinted or dyed her own life the hue of his, this one man’s out of billions mostly unknown. She no longer leaned her life on anyone.”

I find Maytree lovable but not likeable (like some other of men of his generation I have known). —Elizabeth

Any time you visit a beloved place after an absence of decades, you are a time traveler suddenly in the incomprehensible future: Lou treats Maytree’s shock & judgment & squeamishness with a drag show. —Elizabeth

& yet he himself loves scandalizing the neighbors, throwing off convention. When we dismiss convention, we always pick & choose: some conventions are invisibly dear to us. That may be one of the messages of The Maytrees. —Elizabeth

Dillard loves the natural world, but the fabricated world is always running through it, “like a brochette” (like Reevadare & her husbands.) —Elizabeth

“The Little Dipper looked like a shopping cart.”

We get Deary’s beautiful death, & now Maytree’s. Lou’s death is last chronologically, but first in the book, chapters & chapters ago. —Elizabeth

The Maytrees ends with some of the most astonishing prose I have ever read. I have no other gloss or comment on it, at least right now. —Elizabeth

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

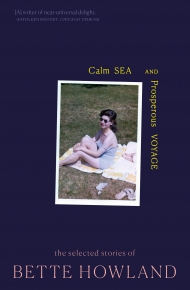

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.