Garth Greenwell | Henry James

#APStogether • July 8, 2020

Read and discuss The Turn of the Screw with Garth Greenwell and A Public Space. Starting July 9, the first in #APStogether, a series of free virtual book clubs that take place on social media under the hashtag #APStogether.

Click here for more information on how it works.

Day 1 | July 9

Reading: Prologue–Chapter 1.

The 1880s were a heyday of "psychical research," which brought pseudoscience to the paranormal. James felt these modern ghost tales were "washed clean of all queerness." His prologue gathers us around a fire, an earlier tradition of storytelling.—Garth

James is famous for refusing to speak plainly, preferring ambiguity & suggestion. This thrills some readers & frustrates others. In Turn of the Screw, James believed the reader would fill in the gaps w/ things more terrifying than he could invent. —Garth

H. G. Wells took James to task for not filling out the character of the governess—but in fact we know a lot. She’s young, naïve, hugely class-conscious, desperate for love, &—maybe most important—prone to thinking of her life as literature. —Garth

Day 2 | July 10

Reading: Chapter 2–3.

My first encounter with James was through Benjamin Britten’s great opera of Turn of the Screw. He brilliantly compresses the first few chapters of the novella, as you can see in the first ~15m of this Opera North production.—Garth

The governess enters into pacts of silence with both the uncle & Mrs Grose. So many of the great stories of evil depend on conspiracies of silence—think of Shakespeare’s Iago, or Iris Murdoch’s Julius King.— Garth

It's such a wonderful touch that, in her first glimpse of the stranger on the tower, the governess is struck by his lack of a hat. What might seem a small breach of etiquette (esp given his more serious trespass!) suggests freedom from all constraint.—Garth

Day 3 | July 11

Reading: Chapter 4–5.

James is my favorite stylist in English, & this sentence is a marvel: at once balanced (“whatever it was that I knew” / “nothing was known”) & thrown off-kilter by inversion (putting the “of” phrase first). It enacts the governess’s bewilderment.—Garth

I'm amazed & chilled by this line every time: these v young children have lost their parents, their grandparents, their previous governess, & have moved continents & been abandoned by their uncle, all in 2 years. How imagine Miles has never suffered? —Garth

Only at the end of Ch 5 does Turn of the Screw definitely become a ghost story. This is one of James’s most famous lines—& many hear it echoed by his friend Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness ("Mistah Kurtz—he dead”), written 1yr after James's story. —Garth

Day 4 | July 12

Reading: Chapters 6–7.

Chs. 6-7 bring to the fore one of the book’s central questions: What exactly did Quint do? What have these children (& Miss Jessel) suffered?

As always, James offers hints, nothing more.—Garth

Another dizzying sentence. The double negative makes it hard to grasp: a perfect way to frame the gov's bizarre certainty. How does she know what she claims to know? She literally refuses to look up at the presence whose identity she’s so sure of.—Garth

In Britten’s opera, Quint & Miss J have larger roles. Q’s first lines are amazingly creepy—a beautiful, florid setting of Miles’s name. Watch the end of Act I here (there's no exact equivalent for this in James).—Garth

Britten wrote the role of Quint for his partner & muse, the tenor Peter Pears, who inspired much of his greatest music. Here’s a photograph I love of a very young, very obviously in love Britten (on the L) & Pears with the composer Aaron Copland.—Garth

Day 5 | July 13

Reading: Chapters 8–9.

James’s difficulty comes from his need to capture feelings too nuanced for standard notation. Here: eagerness for information that confirms a view you're determined not to hold. Is there a German word for that? I don't think there's one in English. —Garth

Sometimes it’s helpful to hear James’s sentences read aloud. The best audio version of Turn of the Screw I’ve found is Emma Thompson's—who, it turns out, did her degree on James. Here she is talking about the novella.—Garth

The governess’s obsession with Miles—& neglect of Flora—is a little breathtaking. James was very good at writing female children—most famously in What Maisie Knew. This story focuses on Miles, but the governess may learn she has underestimated Flora.—Garth

Day 6 | July 14

Reading: Chapters 10–11.

The governess obsessively observes the children, trying to gather evidence. But what evidence would suffice? A boy sneaking out of his room? She wants to see a reality beneath appearances, “the back of the tapestry.” —Garth

I find this exchange heartbreaking. As the governess’s watchfulness—her surveillance—becomes more & more tyrannical, being bad is the only means at Miles’s disposal to assert his freedom. —Garth

Britten sets up Miles’s fascination w/ “badness” in a scene that has no equivalent in James. During a Latin lesson, Miles sings a haunting song on the word “malo” (which can mean “I prefer,” “apple tree,” & “bad”). —Garth

Day 7 | July 15

Reading: Chapters 12–13.

The logic of the witch hunt: the appearance of goodness has become evidence of wickedness. —Garth

The novella is so economical & swift that I always remember the story as taking place over a short time: a few weeks maybe. But in fact it covers months, & the change of seasons is crucial: from green, expansive summer to chill, dark, cramped autumn. —Garth

The uncle is an absence presiding over the drama, & the governess imagines herself in a kind of virtual courtship with him. James, lifelong bachelor & queer observer of the pageantry of heterosexuality, can be absolutely savage about gender politics. —Garth

Day 8 | July 16

Reading: Chapters 14–16.

The governess speaks of Miss Jessel's "indescribably grand melancholy of indifference & attachment.” In this scene Britten gives her one of the great emo arias in opera—& I love her goth style in Opera North's production. —Garth

The challenge of 1st-person narration is making the story bigger than its narrator. James gives us enough of others' reactions to see—perhaps!—around the governess’s view. Here, are we shown how the others manage her increasingly unhinged behavior? —Garth

Though she is constrained by differences of class, education, authority, Mrs. Grose still emerges as the adult in the story who cares most for the children—the only one whose concern is first & foremost their well-being. —Garth

Day 9 | July 17

Reading: Chapters 17–19.

James is the great novelist of introspection—but he is also a very great writer of scenes. Ch 17 is a masterpiece of stagecraft, & ends w/ maybe the book's creepiest moment. A gust of wind, a shriek, a candle blown out—& all the windows shut tight. —Garth

The governess denies the children a past (they have no “history”) & a future (she can only imagine an “extension of the garden & the park”). Here—& earlier w/ Miles, when she thinks of him as “an older person”—she denies them childhood altogether. —Garth

James’s abundant, florid use of metaphor can be difficult. Here we have 2 images: a drawn blade & a spilling cup. Commas before “in a flash” & after “drawn blade” would make it easier to read—but also lose the brilliant tumble & rush of the sentence. —Garth

Day 10 | July 18

Reading: Chapters 20–21.

It’s possible she’s a haunted little demon child, but I love to see neglected, dismissed Flora finally snap at the governess. The sentence snaps too, from the tumble of adjs to the repetition of “and” to the final inversion of adj & noun. The drama! —Garth

In 1934 Edmund Wilson argued that there are no ghosts & the governess “is a neurotic case of sex repression.” This has had a huge influence & led to huge debate, which you can read about here. —Garth

In the 1961 film The Innocents, Deborah Kerr said she played the governess as “perfectly sane.” I love what Truman Capote says about how much work he had to do adapting the book for film. I don’t really love the movie, but many people do! —Garth

Day 11 | July 19

Reading: Chapters 22-24 (The End).

The novella's title is usually read as referring to a torture device: a heightening of tension & so of pain. It appears twice in the text: in the prologue, where that interpretation makes sense—& here. Should virtue be an instrument for torture? I can never read this passage without thinking of T.S. Eliot’s lines, from “Little Gidding”: “Of things ill done & done to others’ harm / Which once you took for exercise of virtue.” —Garth

If I could ask James to resolve just one of the ambiguities in his text I would choose this: of the adults who have proven such grievously inadequate guardians, whom does Miles finally address as “you devil”? —Garth

The final 10 minutes of Britten’s opera both heighten & gesture toward resolving James’s ambiguities. Britten draws out the drama, giving us a grand climax but then letting tragedy unfold in quietness. —Garth

Click here for more information on how it works.

Day 1 | July 9

Reading: Prologue–Chapter 1.

The 1880s were a heyday of "psychical research," which brought pseudoscience to the paranormal. James felt these modern ghost tales were "washed clean of all queerness." His prologue gathers us around a fire, an earlier tradition of storytelling.—Garth

James is famous for refusing to speak plainly, preferring ambiguity & suggestion. This thrills some readers & frustrates others. In Turn of the Screw, James believed the reader would fill in the gaps w/ things more terrifying than he could invent. —Garth

“‘The story won’t tell,’ said Douglas, ‘not in any literal, vulgar way.’

‘More’s the pity then. That’s the only way I ever understand.’”

H. G. Wells took James to task for not filling out the character of the governess—but in fact we know a lot. She’s young, naïve, hugely class-conscious, desperate for love, &—maybe most important—prone to thinking of her life as literature. —Garth

“I had the view of a castle of romance inhabited by a rosy sprite, such a place as would somehow, for diversion of the young idea, take all colour out of story-books & fairy-tales. Wasn’t it just a story-book over which I had fallen a-doze & a-dream?”

Day 2 | July 10

Reading: Chapter 2–3.

My first encounter with James was through Benjamin Britten’s great opera of Turn of the Screw. He brilliantly compresses the first few chapters of the novella, as you can see in the first ~15m of this Opera North production.—Garth

The governess enters into pacts of silence with both the uncle & Mrs Grose. So many of the great stories of evil depend on conspiracies of silence—think of Shakespeare’s Iago, or Iris Murdoch’s Julius King.— Garth

“‘And to his uncle?’

I was incisive. ‘Nothing at all.’

‘And to the boy himself?’

I was wonderful. ‘Nothing at all’”

It's such a wonderful touch that, in her first glimpse of the stranger on the tower, the governess is struck by his lack of a hat. What might seem a small breach of etiquette (esp given his more serious trespass!) suggests freedom from all constraint.—Garth

“—and there was a touch of the strange freedom, as I remember, in the sign of familiarity of his wearing no hat—”

Day 3 | July 11

Reading: Chapter 4–5.

James is my favorite stylist in English, & this sentence is a marvel: at once balanced (“whatever it was that I knew” / “nothing was known”) & thrown off-kilter by inversion (putting the “of” phrase first). It enacts the governess’s bewilderment.—Garth

“Of whatever it was that I knew nothing was known around me."

I'm amazed & chilled by this line every time: these v young children have lost their parents, their grandparents, their previous governess, & have moved continents & been abandoned by their uncle, all in 2 years. How imagine Miles has never suffered? —Garth

“I remember feeling with Miles in especial as if he had had, as it were, nothing to call even an infinitesimal history …. He had never for a second suffered.”

Only at the end of Ch 5 does Turn of the Screw definitely become a ghost story. This is one of James’s most famous lines—& many hear it echoed by his friend Joseph Conrad in Heart of Darkness ("Mistah Kurtz—he dead”), written 1yr after James's story. —Garth

“‘Yes. Mr. Quint’s dead.’”

Day 4 | July 12

Reading: Chapters 6–7.

Chs. 6-7 bring to the fore one of the book’s central questions: What exactly did Quint do? What have these children (& Miss Jessel) suffered?

As always, James offers hints, nothing more.—Garth

“Quint was much too free”

“Vices more than suspected”

“He did what he wished”

Another dizzying sentence. The double negative makes it hard to grasp: a perfect way to frame the gov's bizarre certainty. How does she know what she claims to know? She literally refuses to look up at the presence whose identity she’s so sure of.—Garth

“Nothing was more natural than that these things should be the other things they absolutely were not.”

In Britten’s opera, Quint & Miss J have larger roles. Q’s first lines are amazingly creepy—a beautiful, florid setting of Miles’s name. Watch the end of Act I here (there's no exact equivalent for this in James).—Garth

Britten wrote the role of Quint for his partner & muse, the tenor Peter Pears, who inspired much of his greatest music. Here’s a photograph I love of a very young, very obviously in love Britten (on the L) & Pears with the composer Aaron Copland.—Garth

Day 5 | July 13

Reading: Chapters 8–9.

James’s difficulty comes from his need to capture feelings too nuanced for standard notation. Here: eagerness for information that confirms a view you're determined not to hold. Is there a German word for that? I don't think there's one in English. —Garth

“It suited me too, I felt, only too well; by which I mean that it suited exactly the particular deadly view I was in the very act of forbidding myself to entertain.”

Sometimes it’s helpful to hear James’s sentences read aloud. The best audio version of Turn of the Screw I’ve found is Emma Thompson's—who, it turns out, did her degree on James. Here she is talking about the novella.—Garth

The governess’s obsession with Miles—& neglect of Flora—is a little breathtaking. James was very good at writing female children—most famously in What Maisie Knew. This story focuses on Miles, but the governess may learn she has underestimated Flora.—Garth

“What surpassed everything was that there was a little boy in the world who could have for the inferior age, sex and intelligence so fine a consideration.”

Day 6 | July 14

Reading: Chapters 10–11.

The governess obsessively observes the children, trying to gather evidence. But what evidence would suffice? A boy sneaking out of his room? She wants to see a reality beneath appearances, “the back of the tapestry.” —Garth

“…she conscientiously turned to take from me a view of the back of the tapestry.”

I find this exchange heartbreaking. As the governess’s watchfulness—her surveillance—becomes more & more tyrannical, being bad is the only means at Miles’s disposal to assert his freedom. —Garth

“‘Well,’ he said at last, ‘just exactly in order that you should do this.’

‘Do what?’

‘Think me—for a change--*bad*!’”

Britten sets up Miles’s fascination w/ “badness” in a scene that has no equivalent in James. During a Latin lesson, Miles sings a haunting song on the word “malo” (which can mean “I prefer,” “apple tree,” & “bad”). —Garth

Day 7 | July 15

Reading: Chapters 12–13.

The logic of the witch hunt: the appearance of goodness has become evidence of wickedness. —Garth

“‘Their more than earthly beauty, their absolutely unnatural goodness. It’s a game,’ I went on; ‘it’s a policy and a fraud!’”

The novella is so economical & swift that I always remember the story as taking place over a short time: a few weeks maybe. But in fact it covers months, & the change of seasons is crucial: from green, expansive summer to chill, dark, cramped autumn. —Garth

“The summer had turned, the summer had gone; the autumn had dropped upon Bly and had blown out half our lights.”

The uncle is an absence presiding over the drama, & the governess imagines herself in a kind of virtual courtship with him. James, lifelong bachelor & queer observer of the pageantry of heterosexuality, can be absolutely savage about gender politics. —Garth

“For the way in which a man pays his highest tribute to a woman is apt to be but by the more festal celebration of one of the sacred laws of his comfort."

Day 8 | July 16

Reading: Chapters 14–16.

The governess speaks of Miss Jessel's "indescribably grand melancholy of indifference & attachment.” In this scene Britten gives her one of the great emo arias in opera—& I love her goth style in Opera North's production. —Garth

The challenge of 1st-person narration is making the story bigger than its narrator. James gives us enough of others' reactions to see—perhaps!—around the governess’s view. Here, are we shown how the others manage her increasingly unhinged behavior? —Garth

“‘Master Miles only said ‘We must do nothing but what she likes!’

‘I wish indeed he would! And what did Flora say?’

‘Miss Flora was too sweet. She said ‘Oh of course, of course!’ – and I said the same.’”

Though she is constrained by differences of class, education, authority, Mrs. Grose still emerges as the adult in the story who cares most for the children—the only one whose concern is first & foremost their well-being. —Garth

“‘He didn’t really in the least know them. The fault’s mine.’ She had turned quite pale.

‘Well, you shan’t suffer,’ I answered.

‘The children shan’t!’ she emphatically returned.”

Day 9 | July 17

Reading: Chapters 17–19.

James is the great novelist of introspection—but he is also a very great writer of scenes. Ch 17 is a masterpiece of stagecraft, & ends w/ maybe the book's creepiest moment. A gust of wind, a shriek, a candle blown out—& all the windows shut tight. —Garth

The governess denies the children a past (they have no “history”) & a future (she can only imagine an “extension of the garden & the park”). Here—& earlier w/ Miles, when she thinks of him as “an older person”—she denies them childhood altogether. —Garth

“At such times she’s not a child—she’s an old, old woman.”

James’s abundant, florid use of metaphor can be difficult. Here we have 2 images: a drawn blade & a spilling cup. Commas before “in a flash” & after “drawn blade” would make it easier to read—but also lose the brilliant tumble & rush of the sentence. —Garth

“These three words from her were in a flash like the glitter of a drawn blade the jostle of the cup that my hand for weeks and weeks had held high and full to the brim and that now, even before speaking, I felt overflow in a deluge.”

Day 10 | July 18

Reading: Chapters 20–21.

It’s possible she’s a haunted little demon child, but I love to see neglected, dismissed Flora finally snap at the governess. The sentence snaps too, from the tumble of adjs to the repetition of “and” to the final inversion of adj & noun. The drama! —Garth

“…an expression of hard still gravity, an expression absolutely new and unprecedented and that appeared to read and accuse and judge me—this was a stroke that somehow converted the little girl herself into a figure portentous.”

In 1934 Edmund Wilson argued that there are no ghosts & the governess “is a neurotic case of sex repression.” This has had a huge influence & led to huge debate, which you can read about here. —Garth

In the 1961 film The Innocents, Deborah Kerr said she played the governess as “perfectly sane.” I love what Truman Capote says about how much work he had to do adapting the book for film. I don’t really love the movie, but many people do! —Garth

Day 11 | July 19

Reading: Chapters 22-24 (The End).

The novella's title is usually read as referring to a torture device: a heightening of tension & so of pain. It appears twice in the text: in the prologue, where that interpretation makes sense—& here. Should virtue be an instrument for torture? I can never read this passage without thinking of T.S. Eliot’s lines, from “Little Gidding”: “Of things ill done & done to others’ harm / Which once you took for exercise of virtue.” —Garth

“but demanding after all, for a fair front, only another turn of the screw of ordinary human virtue.”

If I could ask James to resolve just one of the ambiguities in his text I would choose this: of the adults who have proven such grievously inadequate guardians, whom does Miles finally address as “you devil”? —Garth

“‘Peter Quint—you devil!’”

The final 10 minutes of Britten’s opera both heighten & gesture toward resolving James’s ambiguities. Britten draws out the drama, giving us a grand climax but then letting tragedy unfold in quietness. —Garth

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

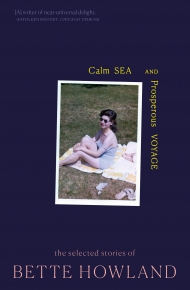

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.