Writing Home: Checking in from Sandpoint

• Keith Lee Morris • October 1, 2013

Thomas Wolfe couldn't go home and William Faulkner couldn't seem to leave very successfully and Ernest Hemingway seemed to be looking for some lost idea of it everywhere and T.S. Eliot apparently found it about five minutes after arriving in England, becoming even paler and more prunish and speaking with an accent, and then you've got Annie Proulx who seems to feel so right at home just about anywhere she is that she can't get a pen in her hand fast enough to suit her, and there's Eudora Welty who says home is where everything begins, really, in whatever little place, to which someone like James Baldwin might say, Yeah, right, it does, and isn't that a bitch, and then F. Scott Fitzgerald comes along and trumps them all by pointing out how home is not just a place, but a place in time, how we're all borne (born?) ceaselessly into the past.

Which is a fancy (or maybe just muddled) way of saying that I arrived in my hometown of Sandpoint, Idaho, again last week, at the end of a ten-day book tour. My last reading was in Moscow, home of the University of Idaho. The owner of the bookstore there, a nice man named Bob Greene who's had me read there before, miscalculated a bit this time around, scheduling my reading on the same day as the Idaho-Boise State football game. The biggest problem wasn't the small crowd, almost all the members of which I knew personally, but the lack of vacant motel rooms. I was traveling with four of my buddies from high school, and we huddled in John's Alley, the local watering hole, trying to figure out what to do besides drink beer. Someone finally mentioned that we might as well go to Sandpoint, and I tapped my ruby red slippers and there I was, a mere three hours later, walking down First Avenue with a group of people I'd known since I was about twelve, effectively thrust back into my childhood and adolescence. We ended the evening, appropriately, playing darts in a bar which, when I was a kid, was the town's only Mexican restaurant, and which, as an adult, I first met my wife in. The town still feels like home, and it's still where most of my fiction is set.

Okay, I know, a lot of writers--a lot of people in general--leave their hometowns and never look back, or they only do so regretfully. Has Tom (not Thomas) Wolfe ever written about Richmond? What's he trying so hard to forget--the ballet lessons he was forced to take there? Can anyone imagine that Donald Barthelme actually grew up in Houston? But I think that writers are, by and large, a bunch that looks steadily, if not ceaselessly, into the past, and that they tend to draw their inspiration more from the way back when than the here and now. Joyce, who went to France and forever wrote about Dublin. Twain, some part of him always attached to that river. Cather, holed up in Greenwich Village but still thinking about the grassy plains.

Me? Home is a small town inside a ring of mountains, on the shore of a massive glacial lake. Population roughly 7,000 now, 4,144 back when I was a teenager (I can remember it exactly from the sign on the bridge into town--at the next census, the number on the sign changed to 4,305). Why do I keep writing about Sandpoint? Here's a three-part theory that I'll advance in regard to writers and their hometowns in general:

1. We're never sure we know anyplace as well as we know our hometowns. We knew things there in a more visceral if less nuanced way, and we remember them better. Maybe we didn't study the mechanisms that drove the local economy or spend a lot of time worrying about the area's geography or hang out at the local museums, things we would do if we wanted to get to know a place nowadays. But we know exactly what it was like when, one winter day, our friend Mike tried to pet the German shepherd that always lay on the sidewalk on Lake Street, and the dog lunged at him and nearly bit off his ear. We can remember exactly how, when the dog sprang, Mike scrunched up his shoulders and shut his eyes tight and made that funny high-pitched sound, how he grabbed our arm with his cold fingers, how his breath came out like dragon smoke between his gritted teeth. And we can remember acutely the embarrassment of the time when we went to the drive-in with the cutest of all the cute cheerleaders, and we were trying to act cool but we were actually very nervous, and we twisted up the ketchup packet until it exploded all over our white pants. Fiction is ultimately memory.

2. We aren't at all sure that the people we are now are really as us as the people we were then. Weren't we more authentically ourselves? Didn't we compromise less? Weren't we not so full of shit? Weren't we more open, more vulnerable, more generous, more easily frightened, on occasion a whole lot more cruel? Didn't we wear ourselves on our sleeves? Weren't the heights higher, the depths lower, and couldn't we go from one to the other in a heartbeat? My God, so much could depend on a single day. The morning didn't break fair, and we didn't get to go to the lighthouse, and we remembered it all of our lives.

3. It's not so much that we can't go home again, it's that we don't go home again. Most of us writer types have moved on to someplace else--the college campus, the big city. Writing about our hometowns is a way of revisiting them. My parents used to own a small house on the Pend O'Reille River. It had a long, sloping lawn that went down to the water and it was very quiet and in the autumn bald eagles nested in the fir trees along the shore. Years after my parents sold the place, I began to realize that it was slipping from my memory. And so I wrote about it, in extremely close detail, using a character who was slowly going blind as a metaphor for the way the place was slowly receding from my mind's eye. A lot of people have asked me about that character, but to me it wasn't the character who mattered--it was getting that place down on paper, before it disappeared. When I walk the streets of Sandpoint now, I'm usually with friends, and I'm usually distracted, and I've usually had a few beers, and the old town isn't the same anyway--it's only when I write about Sandpoint that I'm fully there. In the years after he left, Thomas Wolfe wrote literally millions of words on the subject of his hometown in the North Carolina mountains, Asheville. Which is to say that he did go home again, over and over, every time the pen touched the page.

Back to Top

Author

Keith Lee Morris is the author of a novel, The Greyhound God, and a story collection, TheBest Seats in the House, both published by The University of NevadaPress. His stories have appeared in New England Review, Southern Review, and New Stories from the South 2006. He is completingwork on a new novel, The Dart League King.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

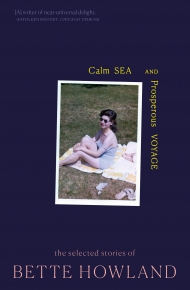

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.