Tolstoy Together

Tolstoy Together • March 16, 2020

****

Dear Friends,

In these unsettled times, like many of you I have been looking for substance in my bookcase. One doesn’t need to look far—there sit the books by Tolstoy, “the master-recorder of realities,” as Stefan Zweig describes him.

In these coming weeks and months, when every one of us has to turn ourselves into a master of living through a harsh reality, I wonder if I could invite you to read and discuss War and Peace with me. I have found that the more uncertain life is, the more solidity and structure Tolstoy’s novels provide. In these times, one does want to read an author who is so deeply moved by the world that he could appear unmoved in his writing.

War and Peace is a perfect book to read together for the duration of our necessary isolation. My edition (translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky) is about 1,200 pages. It will take us about 30 minutes to read 12-15 pages a day (much less than the time many Americans spend on social media), and we will finish the novel in three months—just in time for summer, and with our spirits restored.

Ever yours,

Yiyun Li

How It Will Work

Beginning Wednesday, March 18, I'll select a passage to share with you here as well as on A Public Space's Twitter and Instagram accounts. We hope you'll share your thoughts and responses, and ask questions too. We'll be using #TolstoyTogether to organize the ongoing conversation. There will also be a weekly newsletter, sharing an overview of the week's reading, including highlights from our conversation.

Week 1 (Days 1-4) newsletter

Week 2 (Days 5-10) newsletter

Week 3 (Days 11-17) newsletter

Week 4 (Days 18-24) newsletter

Week 5 (Days 25-31) newsletter

Week 6 (Days 32-38) newsletter

Week 7 (Days 39-45) newsletter

Week 8 (Days 46-52) newsletter

Week 9 (Days 53-59) newsletter

Week 10 (Days 60-66) newsletter

Week 11 (Days 67-73) newsletter

The End (Days 74-85) newsletter

What You Will Need

A copy of War and Peace! Any translation will do; I’ll be reading from the Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky translation. To prepare for the start of the book club on Wednesday (and support your local independent bookstore), order your copy (print or e-book) here or here or an audiobook here. Your public library might also have copies (print and e-book) available too. For anyone unable to access a book, a free PDF is available through Project Gutenberg here.

Day 1 | March 18

Reading: Volume I, Part I, i-iii

Dear Friends, Let’s go—slowly, without rushes, without impatience, without fatigue, without weakness. With some random thoughts from me and many more from you. —Yiyun

“One who sees so much and so well does not need to invent; one who observes imaginatively does not need to create imagination.” —Stefan Zweig on Tolstoy

The skills of a successful soirée hostess—I once told a friend I learned how to host a party from the opening of War and Peace.

“Watching out for an idle spindle or the odd one squealing much too loudly.”

Anna Pavlovna, the hostess, presents the good viscount as a piece of beef. From a dirty kitchen!

Even the best actors lose their confidence! Anna Pavlovna needs the little princess’s support for even the most cliché reply; and the little princess needs an extra prop for her performance.

“Unknown… uninteresting… unnecessary.”

The poor aunt—doesn’t she remind us of Freddy Malin’s mother in Joyce’s “The Dead,” placed at “a remote corner.” In every party there is an unnecessary and inconvenient guest.

One who reads Tolstoy always borrows from him! See Downton Abbey: Prince Vassily loans his surname, Kuragin, to the Russian prince who almost elopes with the Dowager Countess. Kuragin plays chess with his friend Nikolai Rostov, the namesake of Natasha’s brother.

Day 2 | March 19

Reading: Volume I, Part I, iv-vi (partial). (From “Anna Pavlovna smiled” to “Word of honor!”)

“He did not, as they say, know how to enter a salon, and still less did he know how to leave one.”

Pierre reminds me of Winnie the Pooh, and is as dear to me. —Yiyun

Minor characters in War and Peace are never boring. Tolstoy’s footmen remind me of Rebecca West’s description of a butler: “As a Shakespearean courtier by moving a couple paces away…with an air of withdrawing to another part of the forest.” —Yiyun

What is wrong with Prince Andrei? I never quite understand why he marries Lise. Though I have a feeling Kierkegaard would feel sympathetic. (Plagiarizing myself, from an interview with FinancialTimes.) —Yiyun

Day 3 | March 20

Reading: Volume I, Part I, vi (second half) - x. (From “It was past one o’clock” through “She slowly walked beside him to the sitting room.”)

I always think of Paul Lisicky when I read the bear scene. I hope he likes that Pierre (who is called a bear by Prince Andrei) waltzes with a young bear.—Yiyun

My Ukrainian masseuse and I often discuss Tolstoy. Once, I asked her where the bear in the carousing scene came from. She said they must’ve stolen the bear from a circus. I said, Oh, I didn’t think of that.

“What did you think? That bears walk around in Moscow, and they grabbed one off the street?” I thought people would go bear hunting. She said, “In that case, you’d only get a dead bear.”—Yiyun

Countess Rostov had 12 children, but only 4 are alive when the novel opens. Tolstoy only mentions this once (but the lost ones are ever present in what she does).—Yiyun

This is why one likes Pierre. He asks questions everyone wants to dismiss as silly, and yet no one (not even Prince Andrei) can answer them well.—Yiyun

“The sound of several men’s and women’s feet running to the door, the crash of a tripped-over and fallen chair, and a thirteen-year-old girl ran in.” Tolstoy slyly puts a veil over the omniscience so we are the guests now, not knowing… and waiting to see… Natasha. —Yiyun

Not quite an answer to your question: at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s bed was smaller than my son’s single bed; his desk and chair were minute. He was 5’11” but the chair, very low, didn’t look comfortable enough for anyone over 5’2”.—Yiyun

Day 4 | March 21

Reading: Volume I, Part I, xi-xiv. (From “The countess was so tired…” to “But for both of them they were pleasant tears.”)

“You’ve never loved anybody, you have no heart, you’re just a Madame de Genils,” Natasha says to Vera.

Such an insult to Madame de Genils (a writer, perhaps even a good one!) to be compared to the unloved and loveless Vera.—Yiyun

Mirrors: Boris studied “his handsome face”; Vera “her own beautiful face.” LATER, Moscow burning: “The yard porter stood in front of the big mirror, marveling his smile spreading across his face in the mirror.” His first time to see himself in a mirror!—Yiyun

“Pierre had not managed to choose a career for himself in Petersburg.” A perfect opening to a short story. —Yiyun

One of the best war strategists in peace time. —Yiyun

One of the most touching moments between two unsympathetic characters. —Yiyun

Prince Andrei married Lise Meinen. Vera’s beau is Berg (who later will take pride of his German lineage.) A question for the knowledgeable people: what is the history of German presence in Russia in late eighteenth century? —Yiyun

Day 5 | March 22

Reading: Volume I, Part I, xv - xvii. From “Countess Rostov, with her daughters” to “letting out a long, deep breath and pushing up her sleeves.”

“The most agreeable occupation… was the position of listener, especially when he managed to set two garrulous interlocuters on each other.”

I very much share Rostov’s preference: winding up two jumping frogs is better than being wound up + made to jump. —Yiyun

Berg cheers me up: I hope (?) I haven’t reached a point for Tolstoy to lance me with his words.—Yiyun

“The guests try to guess from these glances who or what they are still waiting for: an important belated relation or a dish that is not ready yet.”

Be late, or be complicated—an encouraging motto for all procrastinators. —Yiyun

The prototype of an Instagrammer? Still, I love that the paragraph ends with “love of knowledge.” And I shiver how Tolstoy makes a character transparent. —Yiyun

Day 6 | March 23

Reading: Volume I, Part I, xviii - xx. From “Just as the sixth anglaise was being danced” to “Pierre went out…”

The death of old Count Bezhkhov leads to the first real war in the novel. Bloodless battles are often fought more heartlessly than bloody ones. One feels internally wounded just by reading. —Yiyun

“Outside the house, beyond the gate… undertakers crowded in anticipation of a rich order for the count’s funeral.” Minor characters that deserve a Chekhov story (like “Rothschild’s Fiddle”) —Yiyun

“He went over to him, took his hand, and pulled it down, as if testing whether it was well attached.”

Prince Vassily’s hands speak more eloquently than his words. —Yiyun

Waiting for his father’s death, twice Pierre is described with both hands on his knees, “in the naive pose of an Egyptian statue.” —Yiyun

Day 7 | March 24

Reading: Volume I, Part I, xxi-xxiii.. From “There was no one in the reception room now” to “Go to the dining room.”

The only match for Anna Mikhailovna is Princes Vassily. Such a pity he didn’t court her, but courted her best friend (Countess Rostov) instead. If only they two were a couple—what wouldn’t they have snatched from the world? —Yiyun

“‘Well, aren’t you a fool!’ shouted the prince, shoving the notebook away, but he got up at once, paced about, touched the princess’s hair with his hands.”

Princess Marya is old Prince Bolkonsky’s fool, just as Cordelia is Lear’s fool. —Yiyun

Julia Karagin’s letter saves us from having to read ten more chapters of how Old Count Bezukhov’s will get sorted out. A good gossip is good assistant to a novelist. –Yiyun

Day 8 | March 25

Reading: Volume I, Part I, xxiv-end of Part I.. From “At the appointed hour” to “shook his head reproachfully, and slammed the door.”

Every talker stands on the shoulders of a “wordless” character. –Yiyun

Old Prince “flung away his plate, which was deftly caught by Tikhon.” Some characters need two hundred pages to come alive. Tikhon needs only one line. –Yiyun

Day 9 | March 26

Reading: Volume I, Part II, i-iii.. From “In October 1805” to “But the cornet turned and left the corridor.”

Just as battles played out in the drawing rooms, the battlegrounds turn themselves into drawing rooms. Kutuzov knows more than anyone that the army is just another soiree, and everyone has to stay predictable. —Yiyun

“You are looking at the unfortunate Mack.”

Tolstoy suspends his narrative omniscience when he wants a character’s entrance to be dramatic. Mack shows up as Natasha does, causing a gasp somewhere. –Yiyun

Day 10 | March 27

Reading: Volume I, Part II, iv-vii.. From “The Pavlogradsky hussar regiment” to “Put a stick between your legs, that’ll do you for a horse.”

Despite marches, reviews, battles, retreats, tableaus of historical figures and their fictional subordinates, Tolstoy never lets out of sight Prince Andrei and Nikolai Rostov, who carry the chronology of the war between them. –Yiyun

The Russian officers’ approval of the infantrymen ransacking a village, their jokes about violating the nuns: the civilians’ fates are treated with light—almost jesting—touches until the French army enters Russia. –Yiyun

There must be a word in German to describe this effect? The legato of the scenery to the arresting note of the mounted patrols of the enemy, already within sight.— Yiyun

Day 11 | March 28

Reading: Volume I, Part II, viii-ix.. From “The rest of the infantry” to “A long-past, far-off memory.”

Rostov, sent with his colleagues to set fire to the bridge, could not help “because, unlike the other soldiers, he had not brought a plait of straw with him.” One has to have a soft spot for a boy so bravely playing in a man’s game. —Yiyun

Colors are sometimes “muted” or “loud,” but we don’t often see “transparent” used to describe sounds! —Yiyun

“Two hussars wounded and one killed on the spot,” he said with obvious joy, unable to hold back a happy smile, sonorously rapping out the beautiful phrase killed on the spot.”

The first death in the war, giving the colonel a chance to love his own words. —Yiyun

Day 12 | March 29

Reading: Volume I, Part II, x-xiii.. From “Prince Andrei stayed in Brunn” to “their mutual acquaintance.”

“His thin, drawn, yellowish face was all covered with deep wrinkles, which always looked as neatly and thoroughly washed as one’s fingertips after a bath.”I don’t understand Tolstoy today. Bilibin is 35, and lives comfortably. Who loans him this face? —Yiyun

Prince Ippolit needs only one gesture. His “examining his raised feet through his lorgnette” is as immortal as when he “stood beside the pretty, pregnant princess and looked at her directly and intently through his lorgnette.” —Yiyun

Anyone can write the horror of a dead horse in a war; Tolstoy makes a dead horse deader. –Yiyun

Day 13 | March 30

Reading: Volume I, Part II, xiv-xviii.. From “On the first of November” to “after the disordered French.”

Perhaps when we say we live in history, it means we live in shared disbeliefs rather than individual ones. —Yiyun

“Prince Andrei smiled involuntarily” in the presence of Captain Tushin. Some people inspire awe. Others, jealousy. The best ones are those who make us behave unlike ourselves. —Yiyun

When Tolstoy writes about the war, he is not only writing about the cannonballs and the bodies, but how people act despite the cannonballs and the bodies—sensibly and near illogically. —Yiyun

Day 14 | March 31

Reading: Volume I, Part II, xix-xxi (end of Part II).. From “The attach of the six chasseurs” to “Bagration’s detachment joined Kutuzov’s army.”

Nikolai throwing the pistol and running as if playing tag: anyone can write about the loss of innocence in a war; Tolstoy writes about the return to innocence. —Yiyun

Tushin in action: “He pictured himself as of enormous size, a mighty man, flinging cannonballs at the French with both hands.”

The difference between a man with an ego and a man without one: Prince Andrei’s superhero fantasy is joyless; Tushin’s, gleeful. —Yiyun

The first snow in the novel: as atmospheric as Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1 (Winter’s Dreams); not yet the 1812 Overture. —Yiyun

Day 15 | April 1

Reading: Volume I, Part III, i-ii.. From “Prince Vassily did not think out his plan” to “the counts Bezukhov in Petersburg.”

Pierre being duped into the marriage reminds me of Horton being duped into hatching the egg.

“…especially the youngest, the pretty one with the little mole, who often confused Pierre with her smiles and her own confusion on seeing him.”

A near love story crowded out by the army of society people enlisted into capturing Pierre for Hélène. —Yiyun

Prince Vassily’s family is… complicated. His wife “was tormented by envy of her daughter’s happiness.” Hélène’s brother “Anatole was in love with her and she with him, and there was a whole story.”

No wonder Ippolit needs a lorgnette—so much drama. —Yiyun

Day 16 | April 2

Reading: Volume I, Part III, iii-iv.. From “Old Prince Nikolai Andreich Bolkonsky received a letter” to “And, raising her finger and smiling, she left the room.”

A better husband than Prince Andrei “would seem hard to find these days.” Old Prince Bolkonsky’s parental blind spot is an occasion to try out a word I’ve never used: LOL. —Yiyun

“Our regiment is already on the march. But I’m enlisted—what am I enlisted in, papa?”

Prince Vassily at least has a more clear-eyed assessment of his son—“no genius, but he’s an honest, good lad.” —Yiyun

Bourienne, not the most heartbreaking woman, breaks my heart with her imagination—rather than a fantasy for romance, it’s an orphan’s dream of a reunion with her mother. —Yiyun

Day 17 | April 3

Reading: Volume I, Part III, v-vii.. From “They all dispersed” to “this hateful little adjutant.”

Anatole is predictable, but one has to love him when, caught with Mlle Bourienne, he “with a merry smile, bowed to Princess Marya, as if inviting her to laugh at this odd incident.” A cliché embodying its cliché-ness full-heartedly is ingenious. —Yiyun

Rostov, humiliated by Prince Andrei and fantasizing aiming a pistol at Andrei’s face, “was surprised to feel that, of all the people he knew, there was no one he so wished to have for a friend as this hateful little adjutant.” Touché! —Yiyun

Day 18 | April 4

Reading: Volume I, Part III, viii-ix.. From “On the day after the meeting” to “remained for a time with the Izmailovsky regiment.”

“A third [adjutant] was playing a Viennese waltz on the pianoforte, a fourth was lying on the pianoforte and singing along.”

Unnamed characters and their mysteries: is the singer facing upward, or is he facing the pianist, watching his fingers? —Yiyun

If I were Prince Andrei, I would prefer to be written by anyone but Tolstoy. —Yiyun

“What precision… what foresight of all possibilities, all conditions, all the smallest details!... The combination of Austrian clarity and Russian courage—what more do you want?”

Perhaps a dose of uncertainty, as Napoleon had before the battle? —Yiyun

Day 19 | April 5

Reading: Volume I, Part III, x-xiii.. From “At dawn on the sixteenth” to “worthy of my people, you, and myself. Napoleon.”

We no longer rely on clocks that need winding once a week, and are perhaps less capable of imagining ourselves as cogs and wheels and pulleys. We are as omnipotent as our digital devices. —Yiyun

Kutuzov: “The point of the matter was to satisfy the irresistible human need for sleep.”

Rostov: “Trying to fight off the sleep that was irresistibly overcoming him.”

The most experienced and the most inexperienced fall asleep the night before the battle. —Yiyun

The reading (in German… over an hour…) of the disposition: I have a fantasy of gathering a Zoomful of people to act out the scene. I can do the “significant gaze, which signified nothing.” —Yiyun

Day 20 | April 6

Reading: Volume I, Part III, xiv-xvi.. From “At five o’clock in the morning” to “And thank God!”

“Always and Everywhere”—the most comforting words, even if unsustainable; and the most ominous words, though overly sensational—would make a grander title for a novel than War and Peace.—Yiyun

Tolstoy gives some of the best gestures in the novel to Napoleon, starting with the shedding of a single glove as a historical beginning. —Yiyun

“Looking at the standard, [Prince Andrei] thought: maybe it is that very standard with which I’ll have to march at the head of the troop.”

The standard: not so different from a Russian prince in Mlle Bourienne’s fantasy, or a husband in Princess Marya’s. —Yiyun

Day 21 | April 7

Reading: Part Three XVII-XIX (end of part Three)

“One could see the puffs of gunsmoke as if running and chasing each other on the slopes, and the smoke of the cannon swirling, spreading, and merging together. One could see, from the gleam of bayonets amidst the smoke, the moving masses of infantry and the narrow strips of artillery with green caissons.”

If one could suspend imagining what comes next, one could fall for the inhuman beauty of an advancing troop. —Yiyun

“On the narrow dam of Augesd, on which for so many years an old miller in a cap used to sit peacefully with his fishing rods, while his grandson, his shirtsleeves rolled up, fingered the silvery, trembling fish in the watering can; on this dam over which, for so many years, Moravians in shaggy hats and blue jackets had peacefully driven in their two-horse carts laden with the wheat and had driven back over the same dam all dusty with flour, their carts white—now, on this narrow dam, between wagons and cannon, under horses and between wheels, crowded men disfigured by the fear of death, crushing each other, dying, stepping over the dying, and killing each other, only to go a few steps and be killed themselves just the same.”

One hears the echo of this passage in Isaac Babel’s stories and Hemingway’s novels. –Yiyun

Napoleon, as the victor, was “happy in the unhappiness of others.” Is that better or worse than someone who’s “unhappy in the happiness of others”? —Yiyun

Day 22 | April 8

Reading: Volume II, Part I, i-iv.. From “At the beginning of 1806” to “Everyone was silent.”

Carriage-lifting and slipper-plaiting: either makes him a real character; together they make him unforgettable. —Yiyun

The terrifying power of a childhood home supports Hegel: What is rational is actual; and what is actual is rational. —Yiyun

Pierre is more clear-eyed than most characters in the novel, despite behaving like a bumblebee: he assesses Dolokhov as Tolstoy dissects Prince Andrei, and doesn’t allow the thinnest veil of self-deception when admitting his fear of Dolokhov. —Yiyun

Day 23 | April 9

Reading: Volume II, Part I, v-x. From “‘Well, begin!’ said Dolokhov” to “dinners, evening parties, and balls.”

Dolokhov, the “rowdy duelist, lived in Moscow with his old mother and hunchbacked sister, and was a most affectionate son and brother.”

The girl has only three words given to her. “The Hunchbacked Sister” would be a perfect title for a novella. —Yiyun

When the news of a death arrives, there is always a wheel spinning, or a phone ringing, or a bee buzzing, unaware of its destined connection to forever. —Yiyun

Not everyone deserves a Tikhon in their lives; every Tikhon deserves a Tolstoy. —Yiyun

Day 24 | April 10

Reading: Volume II, Part I, xi-xvi (end of Part I). From “On the third day of Christmas” to “which was already in Poland.”

Is there a less charitable verb than that “seemed”? I feel like taking up a sewing needle as my sabre and challenging that fine word. —Yiyun

Losing at the card game gives Nikolai the same epiphany as the lofty sky gives Prince Andrei, though being destroyed slowly by a friend is a hundred times more terrifying than dying on the battleground. (And terrifying to watch, too.) —Yiyun

Dolokhov plays until Nikolai owes him 43K “because forty-three made up the sum of his age plus Sonya’s.” It’s better to have “a wicked & unfeeling man” (Natasha has good intuition), who operates with adolescent melodrama, as an enemy rather than a friend. —Yiyun

Day 25 | April 11

Reading: Volume II, Part II, i-iii. From “After his talk with his wife” to “with joy and tender feeling.”

Pierre and his Masonic pursuit: I’m delighted to realize that for the three chapters we read today, I have zero Post-it on the pages. (For other chapters I don’t do so well at counting the Post-its.) —Yiyun

“His servant handed him a book cut as far as the middle, an epistolary novel by Mme Souza.”

A new book cut “as far as the middle” is a curious detail: Who cut it? (The servant?) Why only half? (Does he not have confidence in the book?) —Yiyun

Day 26 | April 12

Reading: Volume II, Part II, iv-vii. From “Soon after that, it was not the rhetor” to “an intimate of Countess Bezukhov’s house.”

Pierre’s thought about the Masonic rituals reminds me when, at almost four years old, I couldn’t cry at the memorial service for Chairman Mao. Instead of mourning, I looked around at other kids, and was caught by a teacher. —Yiyun

There are two thermometers in Anna Pavlovna’s drawing room: Napoleon as a political villain, and Pierre as a spoiled and depraved idiot. —Yiyun

I’ve been wrong to think it’s boring to have my characters smile—it’s my fault if their smile is empty. —Yiyun

Day 27 | April 13

Reading: Volume II, Part II, viii-x. From “The war was heating up” to “that is, all they could.”

Friends who are worrying about catching up: Tolstoy was late, running behind schedule. We can be too, while reading War and Peace. As long as nobody is eaten by the bears, we shall prevail. —Yiyun

“It was not what he read in the letter that made him angry; what made him angry was that the life there, now foreign to him, could excite him.”

I keep having an allergic reaction to Prince Andrei, instead of simply being made ill or being made to feel better. It must be a sign of a successful character. —Yiyun

Princess Marya is always vigilant, Prince Andrei fastidious. They both get caught by the canopy of the crib—that muslin speaks eloquently of the subtle yet definitive changes brought by a child. —Yiyun

Day 28 | April 14

Reading: Volume II, Part II, xi-xv. From “Returning from his southern journey” to “Rostov noticed tears in Denisov’s eyes.”

Pierre makes Princess Marya, who’s embarrassed all the time, feel comfortable. Here, he makes old Prince Bolkonsky, who’s often angry and cruel, speak with kindness—possibly the only time in the novel he does so. One has to adore Pierre for his effect on people. —Yiyun

I wondered what Tolstoy’s contemporaries felt about the novel. Turgenev, who had a falling out with Tolstoy, complained often in his letters when he reached where we are in the book. —Yiyun

A few days later, still pondering War and Peace, Turgenev wrote: “It contains intolerable things and astonishing things, and the astonishing things, which essentially predominate, are magnificent; none of us has written anything better.” —Yiyun

Day 29 | April 15Reading: Volume II, Part II, xvi-xxi (end of Part II). From "In the month of April" to "Hey, you! Another bottle!" he shouted.

Denisov and Rostov’s dugout, with dirt steps as anteroom and broken glass as skylight, reminds me that in the army, our commander once had a bed made for her from a butcher’s block borrowed from a village kitchen. A luxury that birthed many jokes. —Yiyun

Seeing Tushin again (alive! still smiling! minus an arm…) puts me into a strange and familiar mood, once named by a friend as: happysad. —Yiyun

Poor Alexander came out of the pavilion before Napoleon—we wouldn’t have learned that detail if not for Boris (and men like him), who devotes his life to insetting his posterity in history. —Yiyun

Day 30 | April 16

Reading: Volume II, Part III, i-v. From "In 1808 the emperor Alexander went" to "trying not to be noticed, left the room."

I’m always tickled and in awe that Tolstoy gives the most romantic moment of the novel to Prince Andrei, the least romantic character. (Like slipping one of Falstaff’s lines into Lear’s script with the uttermost ease.) —Yiyun

Prince Andrei has his “huge, gnarled, ungainly… old, angry, scornful, and ugly” oak tree. Jane Eyre has her lightening-struck chestnut tree, “split down the centre… ghastly.” I have in front of my window a young dogwood tree, blossoming unobtrusively. —Yiyun

Prince Andrei is “an eligible young man, rich and well-born… with the aura of the romantic story of his alleged death and his wife’s tragic end.”

A wife’s death can be as valuable a decoration in society as the St Andrew’s honor earned from the battleground. —Yiyun

Day 31 | April 17

Reading: Volume II, Part III, vi-x. From "During the initial time of his stay in Petersburg" to "if Thou forsakest me altogether."

Pierre’s Masonic career is less memorable than his feeling about it—any decision one makes seems capable of becoming that ground. —Yiyun

I once said in a lecture that omniscient Tolstoy didn’t have any character dreaming in War and Peace. I was wrong. I forgot he let Pierre write about his own dreams in his diary. If someone bores us by recounting dreams, of course it would be poor Pierre. —Yiyun

Pierre prays to god for help “to overcome the part of wrath by gentleness and slowness.” Slowness as a virtue is fascinating. Slow in what way? Thinking? Feeling? Challenging someone to a duel? Reading Tolstoy? —Yiyun

Day 32 | April 18

Reading: Volume II, Part III, xi-xv. From "The financial affairs of the Rostovs" to "the way he does with these ladies."

“It was as if they were ashamed that they loved Vera so little and were now so eager to get her off their hands.”

“Unquestionably beautiful and sensible,” and unloved and uncourted by anyone but Berg: poor Vera sounds like a changeling. —Yiyun

Natasha’s observation of Berg—“he’s so narrow, like a dining-room clock”—corroborates Turgenev’s comment on Tolstoy—“he hates sober-mindedness, system, and science (in a word, German).” —Yiyun

Natasha “speaking of herself in the third person and imagining that it was some very intelligent man saying it about her”: I’ve tried this trick, but to the opposite effect. The adjectives I come up with are not as complimentary as Natasha’s. —Yiyun

Day 33 | April 19

Reading: Volume II, Part III, xvi-xxi. From "Suddenly everything stirred" to "and Berg drew Pierre into it."

When did Old Count Bolkonsky move to the countryside? After his wife died giving birth to Marya? Marya did not grow up in society (yet she’s friend with Julie Karagin). Andrei did and married one of the best society women. Backstories are rabbit holes. —Yiyun

Tolstoy’s omniscience at its best: history and court intrigues play out in the negative space of Natasha’s awareness; what she doesn’t see in “her highest degree of happiness” is what carries the novel. —Yiyun

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Judging by Berg and Vera, a good marriage would be a mirror for the spouses to look at each other as though looking at themselves, and relishing the images. —Yiyun

Day 34 | April 20

Reading: Volume II, Part III, xxii-xxvi (end of Part III). From "The next day Prince Andrei went to the Rostovs'" to "she loved her father and her nephew more than God."

“Yesterday I was tormented, I suffered, but I wouldn’t trade that torment for anything in the world. I’ve never lived before. Only now am I alive, but I can’t live without her.”

Even a person who never doubts his superior mind speaks of love in clichés. —Yiyun

“The resemblance between Natasha and Prince Andrei, which the nanny had noticed during Prince Andrei’s first visit…”

A minor character immortalized by half a sentence: what the mother misses the nanny does not. —Yiyun

Princess Marya’s notion that god’s infinite love for his creation made it necessary for Lise to die in childbirth: I have nothing to say but that this is the most heartless thing I’ve read so far. Blood curdling. —Yiyun

Day 35 | April 21

Reading: Volume II, Part IV, i-v. From "Biblical tradition says that absence of work" to "shyly smiled his childishly meek and pleasant smile."

Nikolai is modeled on Tolstoy’s father; Pierre and Andrei, Tolstoy himself. It’s interesting that this common sense, which neither Pierre nor Andrei has, is called mediocrity. —Yiyun

“Though Danilo was of small stature, seeing him in the room produced an impression similar to seeing a horse or a bear standing there amidst the furniture and accessories of human life.”

Danilo is inimitable among the dead objects and living aristocrats. —Yiyun

There are a hundred and thirty dogs at the hunt. If a dog eats healthily at 3% of its body weight daily, the hounds and the boizois together would consume somewhere between 150 and 200 pounds of raw meat daily. I too worry about the Rostovs’ finances. —Yiyun

Day 36 | April 22

Reading: Volume II, Part IV, vi-viii. From "The old count rode home." to "Things were not cheerful in the Rostovs's house."

Hunting is war in peace time: the wolf is a skirmish leading to the battle of the hare; Nikolai and Illagin talking about irrelevant topics while eyeing each other’s dogs is a variation of Alexander and Napoleon reviewing the two armies affably. —Yiyun

Who doesn’t love a tuneful dog! Nikolai, only recently called mediocre, says one of the oddest and most astonishing things in the novel. His life doesn’t often allow ingenuity, but by nature he is closest to Natasha.

—Yiyun

Inertia and indecisiveness are perhaps under appreciated: they do their share of life-preserving, just as imagination and action do their share of destruction.—Yiyun

Day 37 | April 23

Reading: Volume II, Part IV, ix-xiii (end of Part IV). From "Christmastime came" to "went to Moscow at the end of January."

“What will I give birth to?” she asked the buffoon… “Fleas, dragonflies, grasshoppers,” the buffoon replied.

An oddly thrilling exchange (though Natasha disagrees): She’s fluent in nonsense. He, with an etymologist’s mind, is as nimble-witted as Lear’s clown. —Yiyun

Nikolai falls for Sonya, in a man’s outfit, with cork-drawn mustache. Sonya finds a beloved stranger in Nikolai, in a woman’s dress. Seeing is dis-believing—realigning memory and desire. Who would begrudge love between these two people, new to each other? —Yiyun

“She wrote him classically monotonous, dry letters, to which she herself did not ascribe any significance, and in the drafts of which the countess corrected the spelling errors.”

Day 38 | April 24

Reading: Volume II, Part V, i-iv. From "After the engagement of Prince Andrei" to "try to get the old prince used to her."

Recently my dear friend Elizabeth McCracken used the word “insoluble” in a note, which clarified my muddled mind instantly. Let the insoluble remain so, as long as we can say: “Above all, we read.” —Yiyun

What if we have a #MontaigneByOneself going at the same time—we’d have a place to go in the evening. —Yiyun

“Ah, my God, Count, there are moments when I’d marry anybody!”

Marya never expresses her eagerness to marry but to Pierre. He has a strange effect and leads people off script—they say things that otherwise would remain unsaid even in their private thoughts. —Yiyun

Day 39 | April 25

Reading: Volume II, Part V, v-viii. From "Boris had failed to marry" to "Natasha also began to look."

“Boris had failed to marry a rich bride in Petersburg and had come with the same purpose to Moscow.”

A great opening to a story. The chapter is like a play in which the actors, while performing perfectly on stage, are thinking of their suppers and nightgowns. —Yiyun

Boris dreams too! One even feels a little touched by an unpoetic character’s unpoetic imagination. —Yiyun

Natasha’s hope in the Bolkonskys echoes Nikolai’s shock at the French who wanted to kill him. Since when has the world stopped loving me?—a question all lucky children have to face. —Yiyun

Day 40 | April 26

Day 40 | April 26Reading: Volume II, Part V, ix-xiii. From "The stage consisted of flat boards" to "no answers to these terrible questions."

What would I not give to see Natasha tickle Hélène, that marble statue. Or, better, paint the statue’s nose red. (One has to love a character who allows one wicked laughter.) —Yiyun

Three plain nouns forming a terrifying crescendo. (This also reminds me of Jane Austen’s line: “With them, to wish was to hope, and to hope was to expect.”) —Yiyun

Hélène’s dress always rustles, Anatole’s spurs always jingle: We are almost certain they read nothing. Reading doesn’t proclaim itself with so much fanfare. —Yiyun

Day 41 | April 27

Reading: Volume II, Part V, xiv-xvii. From "Morning came with its cares" to "ran back with him to the troika."

The rehearsal for a farewell is always prettier. The real farewell, at the mercy of what’s not in one’s control, seldom has space for anything touching or solemn. —Yiyun

The poor horses run to their deaths by Balaga: even if they could go to a horse heaven they would still be inconsolable, next to the horses killed in the war. —Yiyun

The unnamed maid assisting Anatole in seducing Natasha: What’s her motivation? Is it money he offers, or her unquestioning loyalty to Natasha, or something that defies logic and interpretation? It’s easy to go down a rabbit hole with a minor character. —Yiyun

Day 42 | April 28

Reading: Volume II, Part V, xviii-xxii (end of Volume II). From "Marya Dmitrievna, finding the weeping Sonya" to "now blossoming into new life."

“She sobbed with that despair with which people weep only over a grief of which they feel themselves the cause.”

The most devastating of all griefs, but at least it’s rare: often we look outward for the causes of our griefs, and find them where we look. —Yiyun

Mlle Bourienne has lived mostly in the country and is an outsider in Moscow. How does she know the rumors? (Is it possible she’s kept in touch with Anatole? Or does she know a Frenchwoman in another house—a governess or a companion?) Does it quite add up? —Yiyun

Pierre seems to be the only man in the novel capable of thinking: “If I were not I.” Others—Andrei, Old Prince Bolkonsky, Rostov, Anatole—think: “It must be so because I am who I am.” —Yiyun

kj

Day 43 | April 29

Reading: Volume III, Part I, i-v. From "Since the end of the year 1811" to "Alexander had sent him off."

It is unlikely that Tolstoy’s time was sensible and comprehensible. Ours is not. Perhaps there’s never a sensible and comprehensible time. Feeling fatalistic about history, though, is easier than feeling fatalistic about what hasn’t yet become history. —Yiyun

Napoleon, or Tolstoy’s Napoleon, has the air of an actor too confident of his performance to realize that he has overacted. —Yiyun

Murat, a lesser actor, slips out of his role easily into his natural self. —Yiyun

Day 44 | April 30

Reading: Volume III, Part I, vi-viii. From "Accustomed though Balashov was" to "presented themselves to Prince Andrei one after the other."

“The whole aim of his speech now was obviously to exalt himself and insult others.”

“...directing his speech…only at proving his rightness and his strength.”

“…was in that state of irritation in which a man has to talk and talk and talk, only so as to prove his rightness to himself.”

Tolstoy must have foreseen future generations’ miseries. Is there any solace in knowing that there is never a unique buffoon, a unique egotist, a unique sociopath, a unique dictator? —Yiyun

“Mlle Bourienne was the same coquettish girl, pleased with herself, joyfully making use of every moment of her life.”

Andrei is good at blaming all his father’s follies on Mlle Bourienne, but “making use of every moment” seems a consistent and democratic approach to life—instead of his own approach of having one epiphany after another. —Yiyun

Childhood is truly a more dangerous neighborhood than cousinhood. They love you, they love you not. Who are they to say they know even remotely who you are? —Yiyun

Day 45 | May 1

Reading: Volume III, Part I, ix-xii. From "Prince Andrei arrived in the general headquarters" to "'Here. What lightning!' they said to each other."

How do we finish this sentence: An American is self-assured because/on the basis of/on the grounds that/precisely because… —Yiyun

“Listening to this multilingual talk, and these suggestions, plans, and refutations, and shouts…” I’m tempted to suggest a Zoom Maypole dance after we sit through these serious and empty discussions at the war council. —Yiyun

They are “the Inseparables”!—the nicknames given to two officers in Vronsky’s regiment in Anna Karenina. The Inseparables is also the title of an early novel of Simone de Beauvoir, recently reported to be published next year. —Yiyun

Day 46 | May 2

Reading: Volume III, Part I, xiii-xviii. From "In an abandoned tavern" to "'And it seemed to her that God heard her prayer."

“A moment later Rostov’s horse struck the officer’s horse in the rump, almost knocking it down.”

The selflessness of Tolstoy’s animals: Rostov’s horse does exactly what Uncle’s dog Rugai has done—“raced with a terrible selflessness right onto the hare.” —Yiyun

“It seemed so natural for Pierre to be kind to everyone, that there was no merit in his kindness.”

Everyone else can stay in 1812. Pierre: Come this way, step into an Aesop’s fable. —Yiyun

“The impression of ongoing life” is the amber that keeps grief secure inside. —Yiyun

Day 47 | May 3

Reading: Volume III, Part I, xix-xxiii (end of Part I). From "Since the day when Pierre, leaving the Rostovs'" to "astonished at what they had done."

In every catastrophe there’s a laden net. —Yiyun

“Petya was counting on the success of his undertaking precisely because he was a child… yet he wanted to make himself look like an old man.”

“Time travels in diverse paces with diverse persons.” Still, one wishes the boy wouldn’t rush so. —Yiyun

Hang in there, Pierre. Those characters who hate you in a brainless manner will love you in the same manner soon! —Yiyun

Day 48 | May 4

Reading: Volume III, Part II, i-iv. From "Napoleon started the war with Russia" to "he spurred his horse and rode down the lane."

Tikhon walking the old Prince Bolkonsky about in the house, looking for a place to sleep: Who among us has a loyal friend like Tikhon, who would, if sleeplessness were a bullet, take it, night after night. —Yiyun

Bald Hills is forty miles east of Smolensk. It comforts one to think of Alpatych listening to the bells on that white night, summer of 1812, for forty drowsy and peaceful miles, before the cannon balls fall near him in Smolensk. —Yiyun

The fire in Smolensk, a prelude to the Fire of Moscow, starts right next to Alpatych—who bears witness for what’s missed by the Tsar and his courtiers, Rostov and his fellow officers, Pierre and the Moscow society. —Yiyun

Day 49 | May 5

Reading: Volume III, Part II, v-vii. From "From Smolensk the troops continued retreat" to "He gave Lavrushka another horse and took him along"

Sometimes a man sees better once he learns how not to be seen. —Yiyun

“The old man still sat as indifferently as a fly on the face of a dead loved one.”

Strange that Andrei sees the plum-stealing girls for the first time as real human beings, yet the old peasant, who sits on the old Prince’s bench, is still seen as a fly. —Yiyun

“All that naked, white human flesh… was flopping about in the dirty puddle like carp in a bucket. This flopping about suggested merriment, and that made it particularly sad.”

Andrei is flopping too. So are most of us. The unflopping ones we cannot trust. —Yiyun

Day 50 | May 6

Reading: Volume III, Part II, viii-x. From "Princess Marya was not in Moscow" to "she was ready to do everything for him and for the muzhiks."

Her father’s death brings Princess Marya to her most humane moment: religion, of little use, has retreated. —Yiyun

One suspects that the architect Mikhail Ivanovich is only waiting to go into a William Trevor story and surprise us all. —Yiyun

“I see through everything seven feet under you” is such an effective threat. I too looked down at the floor underneath me with dread when I read the sentence. —Yiyun

Day 51 | May 7

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xi-xv. From "An hour later Dunyasha came to the princess" to "'Oh, German scrupulosity!' he said, shaking his head."

“She kept thinking about one thing—her grief, which, after the interruption caused by the cares of the present, had already become her past.”

Few things are as consistent as time’s indifference. The interruption today will become the past, too. —Yiyun

At their meeting neither Princess Marya nor Rostov mentions Natasha and Andrei and their broken engagement. For that alone they have already what makes a good couple: some things are better kept unsaid. –Yiyun

“He despised them not with his intelligence, or feeling, or knowledge... He despised them with his old age, with his experience of life.”

I wonder which is preferable: to have that experience of life, or to be rather the target of such contempt. –Yiyun

Day 52 | May 8

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xvi-xix. From "'Well, that's all now!' said Kutuzov" to "three hours from total destruction and flight."

“There’s no need to storm and attack, there’s need for patience and time.”

Patience and time: three simple and enduring words from a novel of more than half a million words. —Yiyun

“The princess was clearly annoyed that there was no one to be angry with.”

Not even with herself? It must be a strange kind of helplessness to have no one to be angry with. —Yiyun

Day 53 | May 9

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xx-xxiv. From "On the morning of the twenty-fifth" to "They'd gone to the estate outside Moscow."

“Twenty thousand of them are doomed to die, yet they get surprised at my hat.”

Oh dear Pierre: it’s your hat today, not the twenty thousand deaths tomorrow, that makes this moment interesting. —Yiyun

I was happy to learn from Edmund White that Tolstoy’s rendition of wartime confusions was influenced by Stendhal, who wrote about the utter confusion at Waterloo in The Charterhouse of Parma. —Yiyun

P. S. Stendhal survived the retreat from Moscow in 1812.

Yes, the world would be a grippingly bleak place if all people spoke aloud their thoughts uncensored. —Yiyun

Day 54 | May 10

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xxv-xxviii. From "The officers wanted to take their leave" to "worthily fulfilled his role of seeming to command."

“Pierre looked at Timokhin with the condescendingly questioning smile with which everyone involuntarily addressed him.”

How I adore Timokhin: without fail, he gives people the opportunity to feel good about themselves. Even Pierre is not immune. —Yiyun

It must be tiresome to live for posterity. Other than winning wars, Napoleon has also to think about winning readers of history. —Yiyun

Along with the portrait of their son, Napoleon’s empress also entrusted a portfolio of letters to Henri Beyle (later known as Stendhal), who traveled to Moscow and later also rescued a beautiful edition of Voltaire from the fire. —Yiyun

Day 55 | May 11

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xxxiii-xxxv. From “The main action of the battle of Borodino” to “vacillating men were comforted and reassured.”

“In battle it is a matter of what is dearest to a man—his own life—and it sometimes seems that salvation lies in running back, sometimes in running forward.”

Literature (and life) would be so boring if that word “seems” didn’t exist. —Yiyun

“If you see so poorly, my dear sir, don’t allow yourself to speak of what you don’t know.”

Alas. To see poorly and to speak of what one doesn’t know are only human. Is there one person who has not erred thus? —Yiyun “In undecided affairs it is always the most stubborn one who remains victorious.”

Some day I would love to write an essay in praise of this pair of underrated virtues: stubbornness and indecisiveness. —Yiyun

Day 57 | May 13

Reading: Volume III, Part II, xxxvi-xxxix (end of part two). From “Prince Andrei’s regiment was in the reserves” to “the hand of an adversary stronger in spirit.”

“A little brown dog with a stiffly raised tail, who, coming from God knows where, trotted out in front of the ranks with a preoccupied air.”

Death is coming for him, too. Only, unlike the soldiers, the dog doesn’t know it. —Yiyun

“The horse, not asking whether it was good or bad to show fear, reared up…. The horse’s terror communicated itself to the men.”

Neither does the horse ask which is the politically and morally correct language to speak, French or Russian. —Yiyun

“The horses were eating oats from their nosebags, and sparrows flew down to them, pecking up the spilled grain. Crows, scenting blood, crowing impatiently, flew about in the birches.”The animals live through war and peace with the same concern: to not starve. —Yiyun

Day 58 | May 14

Reading: Volume III, Part III, i-v. From “For human reason, absolute continuity” to “enormous current of people which carried him along with it.”

“A commander in chief always finds himself in the middle of a shifting series of events, and in such a way that he is never able at any moment to ponder all the meaning of the ongoing event.”

Same for us, as the commanders in chief of our own chaotic lives. —Yiyun

“Malasha also looked at Grandpa. She was closest to him of all and saw how his face winced; it was as if he was about to cry.”

Only a child recognizes the helplessness in Kutuzov’s unshed tears. —Yiyun

“After that, the generals began to disperse with the same solemn and silent discretion as people dispersing after a funeral.”

Bilibin: where art thou? —Yiyun

Day 59 | May 15

Reading: Volume III, Part III, vi-xi. From “Helene, having returned with the court” to “saw any more of Pierre or knew where he was.”

Princess Kuragin, “constantly tormented by envy of her daughter,” bemoans: “How is it we didn’t know it in our long-lost youth?” The apex of Hélène’s success: she makes her mother envy her and regret not having left her father. —Yiyun

“He handed Pierre a wooden spoon, after licking it clean.”

A line that always makes me shiver with joy. —Yiyun

“An axe would be a good thing, a spear wouldn’t be bad, but a pitch-fork would be best: a Frenchman is no heavier than a sheaf of rye.”

The difference between propaganda and comedy is that the author of the former doesn’t laugh at his own creation. —Yiyun

Day 60 | May 16

Reading: Volume III, Part III, xii-xvi. From “The Rostovs remained in the city” to “tried to take along as much as possible.”

“She could not and did not know how to do things if not with all her heart, with all her might.”

One of the best traits: I see it in my favorite people, and I see it every day in our dog, too. —Yiyun

“Moscow’s last day came.” I wonder which other city in history also lives up to this solemn line. Pompei? Paris? —Yiyun

Berg bargaining for furniture and Sonia packing and unpacking and storing things: they both, in their own way, provide relief in this tumultuous time. —Yiyun

Day 61 | May 17

Reading: Volume III, Part III, xvii-xxi. From “Towards two o’clock the Rostovs’ four carriages” to “the troops were now moving forward.”

Andrei in the caleche, Pierre in the crowd, Natasha in the carriage: it’s one of the few scenes they are together in the novel, but never have they carried a conversation among themselves. What one would not give to see the three of them sit down and talk. —Yiyun

“He himself was carried away by the tone of magnanimity he intended to employ in Moscow.”

Napoleon imagining what he will do to Moscow is like Boris envisioning how to spend Julie’s money before he proposes. —Yiyun

“Moscow was empty. It was empty as a dying-out, queenless beehive is empty.”

A dedicated beekeeper, Tolstoy makes a non-beekeeper feel desolate, as he makes a reader two hundred years later feel for the abandoned city. –Yiyun

Day 62 | May 18

Reading: Volume III, Part III, xxii-xxv. From “The city itself, meanwhile, was empty” to “began shouting and dispersing the clustering carts.”

Mishka playing the clavichord with one finger and the yard porter seeing himself for the first time in the mirror—even if they don’t survive the fire of Moscow, they have encountered the essence of life: art and self-reflection. —Yiyun

“See what they’ve done to Russia! See what they’ve done to me!”

How easily catastrophes are taken personally. —Yiyun

“Kutuzov was sitting on a bench by the bridge and playing in the sand with his whip… Rastopchin took a whip in his hand [and] began dispersing the clustering carts.”

Rastopchin is never more stupid than when he’s next to a man thinking with a whip in the sand. —Yiyun

Day 63 | May 19

Reading: Volume III, Part III, xxvi-xxix. From “Towards four o’clock in the afternoon” to “lay down on the sofa and fell asleep at once.”

“In the kitchens, they made fires and, with their sleeves rolled up, baked, kneaded, and cooked, frightened, amused, and fondled the women and children.”

All those domestic verbs preceding “frightened” and then, that most frightening “fondled.”—Yiyun

Pierre imagines assassinating Napoleon while the drunkard Makar Alexeich points the pistol to a servant, calling him Bonaparte: great minds think alike. —Yiyun

“There was nothing terrible about a small, distant fire in a huge city.”

Tolstoy has these one-sentence paragraphs like tightly coiled springs. Reading them, one feels like a mouse caught by a mousetrap. —Yiyun

Day 64 | May 20

Reading: Volume III, Part iii, xxx-xxxiv (end of Volume III). From “The glow of the first fire” to “Pierre was placed separately under strict guard.”

“‘Who is there to put it out?’ came the voice of Danilo Teretyich… and he suddenly gave an old man’s sob.”

Many weep at the fire. Some tears are more painful to read. This is the proud Danilo who, at the hunting, raised his whip at the incapable Count Rostov. —Yiyun

Natasha standing at the open window, listening to the adjutant’s moaning and imagining Andrei wounded: an echo of their first meeting, with Andrei listening to her voice through the open window and imagining her happiness. —Yiyun

“The smoke became thicker and thicker, and it even became warm from the flames of the fire.”

The fatal winter sneaks into the novel: Sonya chilled, Natasha’s feet cold, the French officer looting for boots, the fire making the air not hot but merely warm. —Yiyun

Day 65 | May 21

Reading: Volume IV, Part I, i-v. From “In Petersburg, in the highest circles, a complex struggle…” to “said Nikolai, kissing her plump little hand.”

There’s some talk about a war, Anna Pavlovna has a soirée. The Battle of Three Emperors has been lost, Anna Pavlovna has a soirée. Moscow is burning, Anna Pavlovna has a soirée. Such is the refrain of the novel. —Yiyun

“The lovely countess’s illness came from the inconvenience of marrying two husbands at once.”

An understatement as flawless and hilarious as Hélène’s clever stupidity. —Yiyun

“Princess Marya and her late father, whom Mrs. Malvintsev evidently did not like, and… Prince Andrei, who evidently was also not in her good grace.”

A glimpse of Marya’s mother through the aunt. Family antipathy is fertile ground for the imagination. —Yiyun

Day 66 | May 22

Reading: Volume IV, Part I, vi-x. From “On arriving in Moscow after her meeting with Rostov…” to “depriving him of life, everything, annihilating him.”

“Mlle Bourienne looked at Princess Marya with bewildered astonishment. A skillful coquette herself, she could not have maneuvered better on meeting a man she wanted to please.”

Admirable Bourienne carries a narrative in a bubble, unaffected by war or peace. —Yiyun

“That gaze expressed entreaty, and fear of refusal, and shame at having to ask, and a readiness for implacable hatred in case of refusal.”

This sentence summarizes many human relationships. –Yiyun

Sonya’s whole calculation of telling Natasha about Andrei and writing Nikolai to release him is as exhilarating as her cross-dressing that wins Nikolai’s heart: unexpected and satisfying. —Yiyun

Day 67 | May 23

Reading: Volume IV, Part I, xi-xiii. From “From Prince Shcherbatov’s house, the prisoners…” to “the value or the meaning of a word or act taken separately.”

“He sang songs not as singers do who know they are being listened to, but as birds do, apparently because it was necessary for him to utter those sounds.”

How enviable. I only sing when no one is listening and it is absolutely unnecessary to utter any sound. —Yiyun

“Pierre sensed that, despite all his gentle tenderness toward him, Karataev would not have been upset for a moment to be parted from him.”

Karataev is a balm after the terrible execution chapter… for now. —Yiyun

Day 68 | May 24

Reading: Volume IV, Part I, xiv-xvi (end of Part I). From “On receiving from Nikolai the news” to “solemn mystery of death that had been accomplished before them.”

“Light, impetuous, as if merry footsteps were heard at the door.”

Natasha’s footsteps are the soundtrack of the novel. —Yiyun

Not everyone understands the privilege of the dying. Andrei not only does but also lets it go for a moment, feeling for Natasha and Marya. One of the most sympathetic Andrei moments. —Yiyun

“During the last time they themselves felt that they were no longer taking care of him (he was no longer here, he had left them), but of the nearest reminder of him—his body.”

This line reads differently after one has sat with the dying and the dead. —Yiyun

Day 69 | May 25

Reading: Volume IV, Part II, i-vii. From “The totality of causes of phenomena” to “the push was given which Napoleon’s army was only waiting for to begin its flight.”

“One of the first bullets killed him, the bullets that followed killed many of his soldiers. And for some time his division went on standing uselessly under fire.”

The war has been too long. Even the wordy Tolstoy starts to resort to swift strokes. —Yiyun

The battle of Tarutino is like an enigmatic course on a tasting menu: it has a grand name, it arrives at the right time, and it’s blatantly bland. What on earth is going on? —Yiyun

Day 70 | May 26

Reading: Volume IV, Part II, viii-xii. From “Napoleon enters Moscow after the brilliant victory” to “And Pierre felt that this view obliged him.”

In the letter to Alexander, Napoleon “considers it his duty to inform his friend and brother that Rastopchin has arranged things badly in Moscow.” Chapter after chapter after chapter after chapter on history… and then a wry sentence like that. LOL. —Yiyun

“He ordered his troops to be paid in counterfeit Russian money he had made.”

A hilarious sentence to close a hilarious chapter, after Napoleon’s endearing words to “Citizens!” & “Craftsman and labor-loving artisans!” & “you, peasants.” —Yiyun

What joy to imagine dour Tolstoy on the day he wrote this. —Yiyun

Day 71 | May 27

Reading: Volume IV, Part II, xiii-xix (end of Part II). From “In the night of the sixth to seventh of October” to “along their same fatal path to Smolensk.”

“One had to wait and endure.” “Patience and time, these are my mighty warriors!”

Wait and endure; patience and time. They sound like clichés, but they are life-sustaining words. —Yiyun

“Shcherbinin lit a tallow candle, causing the cockroaches that were gnawing on it to flee.”

As he hears the cricket on the night of Natasha’s dramatic reunion with Andrei, Tolstoy sees the cockroaches as tens of thousands of people’s fates turn. —Yiyun

Day 72 | May 28

Reading: Volume IV, Part III, i-vi. From “The battle of Borodino, with the subsequent occupation of Moscow” to “‘Well, tell me about yourself,’ he said.”

Oh, the long chapters on war strategy. Tolstoy certainly didn’t read someone from 5th century BC, whose name was Sun Tzu and who wrote a more succinct book called The Art of War. —Yiyun

“This wound, which Tikhon treated only with vodka, internally and externally…”

Yet another memorable Tikhon. Tikhon must be among Tolstoy’s favorite names. “Internally and externally” seems physiologically and psychologically sound. —Yiyun

Day 73 | May 29

Reading: Volume IV, Part III, vii-xii. From “Petya, having left his family on their departure from Moscow” to “joyful and calming thoughts, memories, and images that came to him.”

It seemed to him all the time that he was not where what was most real and heroic was now happening. And he hurried to get where he was not.”

Petya rushing to death: one of the most devastating and pointless races on horseback. —Yiyun

Petya falling asleep against his wish; the French drummer boy dropping off because he is hungry and cold and frightened. If only they could be like Sleepy Beauty and wake up in a better time. —Yiyun

“There is no situation in which a man can be happy and perfectly free, so there is no situation in which he can be perfectly unhappy and unfree.”

The perfectly unhappy could be a subject for a novel: literature tends to be crowded with the imperfectly unhappy. —Yiyun

Day 74 | May 30

Reading: Volume IV, Part III, xiii-xix (end of Part III). From “At noon on the twenty-second, Pierre” to “to threaten, but not to lash the running animal on the head.”

“Karataev looked at Pierre with his kind, round eyes, now veiled with tears.”

“Dolokhov’s gaze flashed with a cruel gleam.”

The eyes of the soon to be executed and the eyes of the executor are equaling unsettling. —Yiyun

“They all went, not knowing themselves where they were going or why. The genius Napoleon knew still less than others, since no one gave him orders.”

The inconvenience of being a genius: being loster than all the other lost souls; being lostest, really. —Yiyun

Day 75 | May 31

Reading: Volume IV, Part IV, i-v. From “When a man sees a dying animal” to “a lackey has his own idea of greatness.”

“She saw his face, heard his voice, and repeated his words and the words she had said to him, and sometimes she invented new words for herself and for him.”

If one character from the novel is capable of inventing new words after a death, it has to be Natasha. —Yiyun

“For a lackey there can be no great man, because a lackey has his own idea of greatness.”

Kutuzuv is the “old man in disgrace.” Napoleon is the “grand homme.” For every historical figure in the novel, there’s a lackey plaiting slippers out of cloth trimmings. —Yiyun

Day 76 | June 1

Reading: Volume IV, Part IV, vi-xi. From “The fifth of November was the first day” to “And so he died.”

“Kutuzov did not understand the significance of Europe… For the representative of the national war there was nothing left but death. And so he died.”

And so he died. The death of one of the most memorable characters, delivered in one astonishing line. —Yiyun

Day 77 | June 2

Reading: Volume IV, Part IV, xii-xvi. From “Pierre, as most often happens, felt the whole burden” to “It’s the first time she’s spoken of him like that.”

“Yes, he’s a very, very kind man, when he’s under the influence, not of bad people, but of such people as I.”

Oh the confidence people put in that capital I. —Yiyun

“The face, with its attentive eyes, with difficulty, with effort, like a rusty door opening—smiled.”

One of the most memorable Natasha moments: the first smile after her beloveds’ deaths. —Yiyun

Day 78 | June 3

Reading: Volume IV, Part IV, xvii-xx (end of Volume IV). From “Pierre was taken to the big, well-lit dining room” to “Right, Marie? It has to be so….”

“That same mischievous smile, as if forgotten, remained on her face for a long time.” Natasha’s smile is like her singing: there is only a pause, never a full stop. —Yiyun

“I must do everything to make it so that she and I are man and wife.”

What joy to see Pierre finally make one statement without self-doubt, guilt, uncertainty, philosophical or theological discourse. —Yiyun

Day 79 | June 4

Reading: Epilogue, Part I, i-v. From “Seven years had passed since 1812” to “that gloomy state of mind which alone enabled him to endure his situation.”

“Like a cat, she became accustomed not to the people, but to the house.”

The saddest truth about Sonya: when people she’s attached to fail her, she reattaches herself to a place and a position. —Yiyun

“He thought of how she would be when he, as an old man, started taking her out, and would do the mazurka with her, as his late father used to dance the Daniel Copper with his daughter.”

From a quick-tempered hussar to a family man, Nikolai’s progress speaks of something real and comforting: characters do change, so do people. –Yiyun

Day 80 | June 5

Reading: Epilogue, Part I, vi-ix. From “At the beginning of winter, Princess Marya came to Moscow” to “which she involuntarily remembered at that moment.”

Nikolai’s making “it a rule to read all the books he bought” reminds me of a friend who makes a rule never to comment on a book she hasn’t read—an essential element of democracy, though in reality people often rush to convictions before knowing and understanding. —Yiyun

“Like a cat, she became accustomed not to the people, but to the house.”

The saddest truth about Sonya: when people she’s attached to fail her, she reattaches herself to a place and a position. —Yiyun

From a quick-tempered hussar to a family man, Nikolai’s progress speaks of something real and comforting: characters do change, so do people. —Yiyun

Day 81 | June 6

Reading: Epilogue, Part I, x-xiii. From “Natasha was married in the early spring of 1813” to “when the stockings were finished”

I, for one, want to applaud Natasha as a wife and a mother: she’s consistently herself, caring only about what matters to her (not society but her family), and doing things with all her might (including nursing her own children, “an unheard-of thing”). —Yiyun

“He wanted to be learned and intelligent and kind, like Pierre.”

Andrei should be happy that his son, brought up by Marya, has such a discerning mind. —Yiyun

Day 82 | June 7

Reading: Epilogue, Part I, xiv-xvi (end of Part I). From “Soon after that, the children came to say good night” to “I’ll do something that even would be pleased with…”

“She felt a submissive, tender love for this man, who would never understand all that she understood.”

Oh, happy marriages: Marya’s love for Nikolai has an echo in Vera’s attitude toward Berg. —Yiyun

“One thing confused her. It was the fact that he was her husband.”

Natasha is one rare character who doesn’t feel shy about acknowledging her confusions, especially the irrational ones. —Yiyun

Day 83 | June 8

Reading: Epilogue, Part II, i-iv. From “The subject of history is the life of peoples and of mankind” to “we will get the history of monarchs and writers, and not the history of the life of peoples.”

Still, every time I make a point of reading every word in Epilogue, Part Two, the smart and the baffling and the repetitive. I’m not embarrassed to say that this feels like a mental tug-of-war with Tolstoy. I won’t feel at peace if I give in. —Yiyun

Day 84 | June 9

Reading: Epilogue, Part II, v-viii. From “The lives of peoples cannot be contained” to “from their plastering point of view, everything comes out flat and smooth.”

Clive James said he could finish War and Peace in one breath if there were a long enough breath. I could imagine a long breath last until the last fifty pages, where I do feel I need several breaths. —Yiyun

Day 85 | June 10

Reading: Epilogue, Part II, ix-xii (THE END). From “For the solution of the question of freedom and necessity” to “it is just as necessary to renounce a nonexistent freedom and recognize a dependence we do not feel.”

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

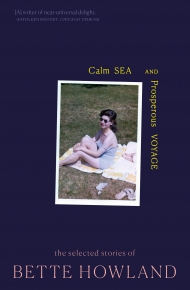

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.