Sarah Shun-lien Bynum | Muriel Spark

#APStogether • September 30, 2020

Read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark with Sarah Shun-lien Bynum in the seventh installment of #APStogether, our series of virtual book clubs. Details about how #APStogether works can be found here.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie invites us into a world that feels heartbreakingly distant right now: a school classroom, filled with young minds and restless bodies and desks and noise and essays on how you spent your summer vacation. At the helm of our classroom is the indelible Miss Brodie, a character of magnificent convictions and questionable judgment who exercises outsized influence on her coterie of handpicked students, with unpredictable results. In this time of pervasive brain fog, I can’t imagine a more bracing antidote than the nimble storytelling and brilliant, funny, incisive sentences of Muriel Spark.

Sarah Shun-lien Bynum is the author of two novels, Madeleine Is Sleeping and Ms. Hempel Chronicles, and most recently a story collection, Likes (FSG). She lives in Los Angeles.

Reading Schedule

Day 1 | October 1: Ch. 1, pp. 1-11

Day 2 | October 2: Ch. 2, pp, 13-26 (through “'That is the order of the great subjects of life, that’s their order of importance.'”)

Day 3 | October 3: Finish Ch. 2, pp. 26-41

Day 4 | October 4: Ch. 3, pp. 43-55 (through “photographing this new Miss Brodie with her little eyes.”)

Day 5 | October 5: Ch. 3, pp. 55-70 (through “with her little pig-like eyes”)

Day 6 | October 6: Finish Ch. 3, pp. 70-78

Day 7 | October 7: Ch. 4, pp. 79-82 (through ““only the squares on the other two sides”)

Day 8 | October 8: Finish Ch. 4, pp. 92-104

Day 9 | October 9: Ch. 5, pp. 105-121

Day 10 | October 10: Ch. 6, pp. 123-137 (The End)

Day 10 | October 10

Ch. 6, pp. 123-137 (The End)

The economy of her method: at the end of Chap 5, physical details like the bicycle boys and the tram-car stop tell us that we’ve completed the temporal lap and arrived back at the novel’s opening scene. An elegant way to re-introduce Joyce Emily in Chap 6

“One of Joyce Emily’s boasts was that her brother at Oxford had gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War.” He would have been among the 4000 Brits, including George Orwell, who joined the anti-Franco forces. See also Colin Firth in “Another Country.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-13937616

Joyce Emily, Mary Macgregor, Miss Brodie: so many sacrifices for such a short novel.

Sandy “wondered to what extent it was Miss Brodie who had developed complications throughout the years, and to what extent it was her own conception of Miss Brodie that had changed.” Good question.

If you wondered in Ch 2 how Sandy’s thoughts on groups/fascisti might relate to her future as a nun, Spark hasn’t forgotten you: "she had entered the Catholic Church, in whose ranks she had found quite a number of Fascists much less agreeable than Miss Brodie.”

“She left the man and took his religion”: Sandy’s difficult love for Miss Brodie leads her to Teddy Lloyd which leads her to Catholicism, a movement that reminds me of Charles Ryder’s journey from Sebastian to Julia to Catholicism in Brideshead Revisited.

“Her mind was as full of his religion as a night sky is full of things visible and invisible.” Spark’s vision of Catholicism begins to emerge as one of vastness, mystery, beauty. A huge & glimmering cosmos that shrinks our human problems down to size.

Sandy, “thinking that it was not the whole story.” Miss B, “trying quite hard to piece together a whole picture.” Resisting wholeness, Spark builds her novel out of catchphrases, snippets, echoes, epithets, bits of poetry & song, flashes forward & back.

Stephen Schiff: “[Spark] lays out the jigsaw pieces over and over…but refuses to cough up the final piece—she trusts her reader to catch on without it. Hence, we finish ‘TPOMJB’ having been told everything about Sandy’s betrayal except why it happens.”

Sandy/Sister Helena clutching the bars of the grille more desperately than ever: what is she yearning to escape? Or hold on to? It’s an image that lingers, full of disturbance and mystery.

Spark in TNY, 5/93: “You have to live with the mystery. That’s the answer in my books."

“There was a Miss Jean Brodie in her prime”: One final repetition, and Sandy’s answer now echoes—almost unbearably—with the accumulation of time and consequences and loss.

Day 9 | October 9

Ch. 5, pp. 105-121

Dierdre Lloyd, alt-version of Scottish womanhood: peasant clothes, languid & long-armed, unbothered & informal. Miss B, Miss Lockhart, Dierdre: studying non-parental adults is such a big part of growing up, a key to figuring out who & how you want to be.

Miss Brodie’s role as Mr Lloyd’s muse is made amusingly literal in one portrait after another (I have a dim memory of this effect being grotesque in the movie), while Dierdre is in the thankless role of artistic helpmeet: “We swathed her in red velvet.”

Any romantic notions I might have had about Teddy Lloyd are shattered by his disgusting wet kiss & vicious words to Sandy. Similarly, any faith I might have had in the integrity or merit of Miss B’s “great love.” Spark disabuses me swiftly & severely.

The cozy bohemian chaos of the Lloyds’ home life—also the dangerous erotic energy circulating between adults and adolescent girls—reminds me of one of my favorite Deborah Eisenberg stories, "The Custodian.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1990/03/12/the-custodian

Spark’s word choices always land just right, managing never to sound contrived or fussy. Miss B “refused him all but her bed-fellowship & her catering”—a very funny but also utterly precise & revealing way of describing the sex & food she provides Mr. L.

As the girls age & grow apart, as Miss Brodie’s schemes further distort her, I begin to miss the earlier chapters’ buoyancy & verve—Paul Lisicky’s lovely term is “comic snap”—I notice more summary & explanation, pieces being moved around the chess board.

But still the explanations dazzle: “she began to sense what went to the makings of Miss Brodie who had elected herself to grace in so particular a way and with more exotic suicidal enchantment than if she had simply taken to drink like other spinsters.”

“They all belong to the Fabian Society & are pacifists”—GB Shaw also belonged to the socialist organization, which advocated for gradual reform & not revolutionary overthrow. Militant Miss B (“gladiator w raised arm & eyes flashing like a sword”) scoffs!

“He had confidence in Miss Lockhart, as everyone did, she not only played golf well and drove a car, she could also blow up the school with her jar of gunpowder and would never dream of doing so.” I love the implication that Miss Brodie very well might.

Day 8 | October 8

Finish Ch. 4, pp. 92-104

Blood tells: Miss B divests this phrase of any pejorative sense, proudly claiming her wild ancestor. “He died cheerfully on a gibbet of his own devising” recalls being hoist with one’s own petard. Either gruesome end could describe Miss B’s downfall.

There’s something plainly witchlike about the excitement and insistence with which Miss Brodie feeds Mr. Lowther. Lobster salad, liver paste sandwiches, cake & tea, porridge & cream. An astonishing array of cholesterol. “You must be fattened up, Gordon.”

She’s also like a fairy tale giant: “Miss Brodie was doing something to an enormous ham prior to putting it into a huge pot.” Their affair seems doomed by incongruities of scale: grand and heroic Miss B, short and slight Mr. Lowther. They don’t fit.

Parul Sehgal: “[Spark] loves reminding us that every word—this phrase, that comma—was brought together by human hands, for your pleasure.” And her characters love discussing word choice, phrasing, etymology, usage: “The word ‘like’ is redundant…”

Spark keeps returning to Mr. Lloyd’s arm for comedy. On him looking romantic: “‘I think it was his having only one arm,’ said Jenny. ‘But he always has only one arm.’ ‘He did more than usual with it,’ said Sandy.” Irreverent Spark never tires of the joke.

Spark does nature sparingly, but she makes it count: “There was a wonderful sunset across the distant sky, reflected in the sea, streaked w blood & puffed w avenging purple & gold as if the end of the world had come without intruding on every-day life.”

At the bottom of p.103, a virtuosic single-sentence paragraph moves us cruelly from elation to disgust. A beautiful, spontaneous expression of youth and freedom—the girls running down the beach—resolves darkly into Miss Brodie’s holiday plans with Hitler.

Though Spark doesn’t make a big fuss over it, I keep noticing how lovely Sandy &Jenny’s friendship is: their closeness & loyalty; their compatibility as co-creators; their holidays spent following the sheep about, full of fresh plans & fondest joy.

Spark’s childhood best friend was named Frances Niven. Here are some lovely archival glimpses of their friendship, as well as the girls’ school and the teacher that inspired the writing of Spark’s novel.

https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=17105

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/muriel-spark-early-writing/

Day 7 | October 7

Ch. 4, pp. 79-82 (through ““only the squares on the other two sides”)

James Wood observes, “In the course of the novel we never leave the school to go home, alone, with Miss Brodie. We surmise that there is something unfulfilled and even desperate about her, but the novelist refuses us access to her interior. This comment surprises me a little because Spark establishes so clearly the nature of her portrait. I would no more expect to go home with Miss Brodie than to overhear the inner thoughts of Jay Gatsby. To me the very title betokens myth, not interiority.

I don’t know which repetition makes me more sad: Mary Macgregor running hither and thither in the science room, terrified by the magnesium flares; or Miss Lockhart, quite the nicest teacher in the school, already feeling exasperation at Mary’s dull face.

In another tidy origami fold of future time, Spark compares Sandy’s regret regarding Mary with Miss Brodie’s. While Sandy suggests that fate/divine authority may be punishing her for her unkindness, Miss B’s regret takes the form of worldly suspicions.

Miss Mackay’s plot is deliciously foiled by Mary’s sheer denseness & two years of Miss Brodie’s indoctrination regarding the evils of team spirit. Her stirring celebrations of “individualism” serve a fascistic desire to maintain control over her own team

“[Jenny] did not again experience her early sense of erotic wonder in life until suddenly one day when she was nearly forty, an actress of moderate reputation married to a theatrical manager.” I find this statement quietly devastating on two levels.

First is the sad fact that Jenny goes for nearly 30 years without feeling “that same buoyant and airy discovery of sex,” & when she finally does in Rome (a city beloved by Miss B), she can’t act on it: “there was nothing whatever to be done about it.”

Second is the flat and nearly dismissive description of Jenny’s professional life—yet she really did become an actress! So what she’s not Sybil Thorndike. She has dedicated herself to a vocation & made a life out of it. The narrator seems unimpressed.

Consoling, though, is the gentle, expansive note on which Spark ends Jenny’s flash-forward: “the concise happening filled her with astonishment whenever it came to mind in later days, and with a sense of the hidden possibilities in all things.”

“She was by temperament suited only to the Roman Catholic Church; possibly it could have embraced, even while it disciplined, her soaring and diving spirit, it might even have normalised her.” It’s tempting to read this as a gloss on Spark’s conversion.

“A creeping vision of disorder”: is this what Sandy experiences as a result of Miss Brodie’s influence and selective amorality? I wonder if this uneasiness compels Sandy toward Catholicism—does it restore her sense of order, renew her “moral perception”?

Day 6 | October 6

Finish Ch. 3, pp. 70-78

The transfiguring power of the incongruous adverb: “Jenny, out walking alone, was accosted by a man joyfully exposing himself beside the Water of Leith.” Even on the subject of flashers, we can expect Spark to say the unexpected

“‘Nasty’ or ‘nesty’?” Why does this pronunciation provoke Sandy’s revulsion? Is it too provincial & Scottish-sounding, lacking the elegant English vowels for which she is famous? Or does she associate ‘nesty’ w/ nests, eggs, the icky end product of sex?

“‘Nasty’ or ‘nesty’?” Why does this pronunciation provoke Sandy’s revulsion? Is it too provincial & Scottish-sounding, lacking the elegant English vowels for which she is famous? Or does she associate ‘nesty’ w/ nests, eggs, the icky end product of sex?

At 11, my daughter also developed a strong dislike for the word “nasty” (especially how her classmates pronounced it: “naaaahsty”). The other word she despised the sound of was “cohort.” Now “nasty” feels inseparable from Trump’s misogynistic use of it.

Sandy’s ongoing fantasies about the “wonderful policewoman” (Sgt. Anne Grey—a delightfully sober name bestowed by Sandy) further encourage me to read her character through a queer lens. A pattern is emerging, esp. as revealed via Sandy’s inner life.

“Alan Breck clapped her shoulder and said, ‘Sandy, you are a brave lass’” VS “Sgt. Anne pressed Sandy’s hand in gratitude; and they looked into each other’s eyes, their mutual understanding too deep for words.” A semicolon lets us linger on their touch.

See also: Sandy & the Lady of Shalott; Sandy’s rapturous description of Miss Lockhart & the science room; Sandy wondering “if Jenny, too, had the feeling of leading a double life, fraught with problems that even a millionaire did not have to face.”

Even in her fantasy world, Sandy still wears her hat in the same way she does at school: “So Sandy pushed her dark blue police force cap to the back of her head.” The commingling of fantasy and reality is a tendency in both Miss Brodie and her girls.

“We’ve got to find out more about the case of Brodie.” The real heart of the investigation is not what Miss Brodie is doing with Lowther/Lloyd/Rose but how Sandy feels about it; she’s grasping at “something,” trying to “work out her reasons.” Repeatedly.

They placed Miss Brodie on the lofty lion’s back of Arthur’s Seat, with only the sky for roof & bracken for a bed.” Arthur’s Seat is an ancient volcano, which makes the girls’ chosen location for Miss B & Mr. L’s sexual intercourse all the funnier to me

Day 5 | October 5

Day 5 | October 5

Ch. 3, pp. 55-70 (through “with her little pig-like eyes”)

Spark in The New Yorker, 5/93: “Well, suspense isn’t just holding it back from the reader. Suspense is created even more by telling people what’s going to happen. Because they want to know how. Wanting to know what happened is not so strong as wanting to know how.”

A sympathetic detail: Miss Brodie sagging gratefully against the door once she’s within the safety of her own classroom, having run the gauntlet of the Junior school corridors. Maintaining aloofness & superiority with scornful colleagues can take a toll.

p57-58: “Monica’s anger” to “past my prime.” In less than a page, we flit effortlessly through FIVE distinct time periods: the girls in ’31; Rose at 16; Monica in late 50s; Sandy & Miss B at tea; the moment (?) when Sandy learns Lloyd really did kiss.

Miss B, diminished: in another flash-forward to after the war, the sight of her “shrivelled & betrayed” in her musquash coat so unsettles me that I want to look away and stare at the hills, like Sandy. Her cancer & early death leave me curiously cold here.

Teachers need epithets too. Mr. Lowther, shy and short-legged; Mr. Lloyd, golden-locked and one-armed. And Miss Gaunt? Gaunt. Did Spark really just do that? She is so punk rock. Short, fast, brutal, irreverent, gleefully repeating the same three chords.

Just in case you might have been wondering who betrayed Miss Brodie, Spark quickly destroys that conventional source of suspense. And does so in a typically nonchalant manner: “It is seven years, thought Sandy, since I betrayed this tiresome woman.”

Thomas Mallon: “When Spark inclines to greater intimacy, it is not toward the character but toward the reader.” The casual mention of Sandy’s betrayal makes us privy to information that only Sandy and the omniscient narrator possess; it’s our three-way secret.

It’s difficult for me to resist Miss Brodie in those moments when she gives voice to my own prejudices in such a commonsensical & amusing way: her dismay, for instance, that Eunice “was taking a suspiciously healthy interest in international sport.”

Day 4 | October 4

Ch. 3, pp. 43-55 (through “photographing this new Miss Brodie with her little eyes.”)

Chapter 3 begins: "The days passed and the wind blew from the Forth.” The omniscient narrator is clearing her throat—wryly invoking the forces of time and weather—as a prelude to the sweeping commentary on history and society she’s about to entertain us with.

Her own kind: A lively sociological portrait of “progressive spinsters of Edinburgh” clarifies that Miss Brodie’s attitudes and enthusiasms were by no means unusual in the 30s. The Schlegel sisters from Howard’s End: possible forebears to these vigorous women?

Nothing outwardly odd about Miss B, but “Inwardly was a different matter, and it remained to be seen, towards what extremities her nature worked her.” How and in what direction will her fluctuating nature grow? Therein lies the suspense. No need to conceal plot.

At the start of the new term, headmistress Miss Mackay gives a rushed speech to Miss B’s class, saying several of the exact same things she said the year before. “Education factory” now seems a fair assessment. When to trust Miss B’s opinions, and when not to?

The Brodie set on Mr. Lloyd, the art master: “Most wonderful of all, he had only one arm, the right, with which he painted. The other was a sleeve tucked into his pocket. He had lost the contents of the sleeve in the Great War.” Spark commits fully to the little girls’ perspective. The Great War is an abstraction to them, remote & unimaginable—they regard the amputated arm with solemn delight. Which then gives me permission to laugh at the careful, dignified tone of that last sentence.

I love the freedom with which Spark creates compound words. My favorite today is “sex-wits.” At one end of the sex spectrum is witless Mary, at the other end is Rose, all instinct and no curiosity: in between is Sandy and Jenny, endlessly fascinated and mystified.

I so recognize from my own childhood Sandy’s impulse to perform for her friends—the irresistible high of hamming it up, even as with each repetition the performance grows more broad & ridiculous & manic—“a state of extreme flourish.” See Maya in PEN15.

Day 3 | October 3

Finish Ch. 2, pp. 26-41

Another bold flash-forward, starring Eunice the gymnast: we leap ahead to 1949, when the Edinburgh Festival was still new. It was founded in 1947 to provide “a platform for the flowering of the human spirit” in the aftermath of WW2. Miss B would approve.

Major revelations in the flash-forward: Miss B’s premature death, forced retirement, and betrayal by one of her girls. Dramatic twists that many novelists would guard jealously. What does Spark gain by disclosing this information so lightly, so early on?

“They approached the Old Town which none of the girls had properly seen before, because none of their parents was so historically minded as to be moved to conduct their young into the reeking network of slums which the Old Town constituted in those years.”

“Now they were in a great square, the Grassmarket, with the Castle, which was in any case everywhere, rearing between the big gap in the houses where the aristocracy used to live.”

“Now they were in a great square, the Grassmarket, with the Castle, which was in any case everywhere, rearing between the big gap in the houses where the aristocracy used to live.”

“Then the group-fright seized her”: Sandy’s neologism perfectly captures the psychology that keeps her in thrall to Miss Brodie & a member of the Brodie set even as her misgivings mount. Her insight about Miss B’s jealousy of “rival fascisti” is spot-on.

“Then the group-fright seized her”: Sandy’s neologism perfectly captures the psychology that keeps her in thrall to Miss Brodie & a member of the Brodie set even as her misgivings mount. Her insight about Miss B’s jealousy of “rival fascisti” is spot-on.

Our third flight into the future & maybe the most amazing so far: we meet Sandy in her middle age & she is now Sister Helena! A girl raised in a city of Presbyterians, in a “believing but not church-going” family. Spark too became a Catholic as an adult.

It seems fitting that Sandy, with her talent for transforming the boredom of a long walk into an ardent conversation with Alan Breck of Kidnapped, should one day write a treatise called “The Transfiguration of the Commonplace.”

A further refinement of what Edinburgh signifies: “We of Edinburgh owe a lot to the French. We are Europeans.” Edinburgh = pragmatic, respectable, but also cosmopolitan, continental? Maybe the city is as rich in contradictions as Miss Brodie herself.

On the subject of contradiction, here’s Spark on the word nevertheless: “It is my own instinct to associate the word, as the core of a thought-pattern, with Edinburgh particularly…The sound was roughly ‘niverthelace’ & the emphasis was a heartfelt one.”

More from Spark: “I believe myself to be fairly indoctrinated by the habit of thought which calls for this word…I find that much of my literary composition is based on the nevertheless idea.” I’m going to hold nevertheless in my mind as we keep reading.

“A very long queue of men…Monica whispered, ‘They are the Idle.’” A sobering glimpse of UK’s struggling economy in the 20s & 30s: the Depression hit northern England & central Scotland particularly hard. See Orwell’s “The Road to Wigan Pier” for more.

Miss Brodie on the Unemployed: “Sometimes they go and spend their dole on drink before they go home, and their children starve. They are our brothers. Sandy, stop staring at once. In Italy the Unemployment problem has been solved."

A typical Brodie hodgepodge, hilarious for its lack of transitions: Moral superiority! Compassionate egalitarianism! Mind your manners! Hooray for Mussolini’s regime!

Day 2 | October 2

Ch. 2, pp, 13-26 (through “'That is the order of the great subjects of life, that’s their order of importance.'”)

Chap 2 begins with the girl whose death was just introduced so suddenly: hapless and lumpy Mary Macgregor. Spark remains unsparing (even as an adult Mary “was clumsy and incompetent”) yet she also creates an understated sense of pathos with this character.

The Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was founded during WWI: “Join the Wrens today and free a man to join the Fleet.” The WRNS reached its largest size in 1944, with 74,000 women doing over 200 different jobs. Mary was clumsy but she answered the call.

“She ran one way; then, turning, the other way; and at either end the blast furnace of the fire met her. She heard no screams, for the roar of the fire drowned the screams; she gave no scream, for the smoke was choking her.”

Brilliance at the sentence level: Spark uses short phrases, strong punctuation (semi-colons most notably), and repetition (parallel syntax, the tripling of “scream”) to capture Mary’s bewildered back-and-forth movement along the smoke-filled hotel corridor.

As quickly as we leapt ahead, we return to the past—without even a paragraph break. In one sentence Mary stumbles and dies; in the very next she is ten again, “sitting blankly among Miss Brodie’s pupils.” The abrupt shift, the juxtaposition: strangely poignant.

“One-armed Mr. Lloyd, in his solemnity, striding into school”—his missing arm is yet another loss from WW1, and how jarring to encounter it right on the heels of the girls’ uproarious imaginings: Mr. Lloyd committing sex with his wife while wearing pyjamas!

Edinburgh, the novel suggests, is more than just a city: it’s an entire way of being. Sandy is embarrassed by how her English mother differs from “the mothers of Edinburgh” in their practical tweed or musquash (apparently muskrat fur is long-lasting).

The overheated prose in Sandy and Jenny’s masterpiece, “The Mountain Eyrie,” is a wonderful piece of comedy, but in its midst is a small, wistful detail. When little pig-eyed Sandy describes her fictional alter ego, she writes “her large eyes flashed.” If only!

The omniscient narrator gets quite close to Sandy’s thoughts in these pages. We see her sensitivity, her secret ferocity, the richness of her 10-year-old imagination. We also see the conflict between her internal and external worlds: Miss B misunderstands her.

My favorite moment of Sandy’s interiority: “The evening paper rattle-snaked its way through the letter box and there was suddenly a six-o’clock feeling in the house.” How do you interpret Sandy’s six o’clock feeling? To me it feels bleakly soul-dampening.

Creepy behavior from the singing teacher, Mr. Lowther, with a tacit OK from Miss B: “He twitched [Jenny’s] ringlets…as if testing Miss Brodie to see if she were at all willing to conspire in his un-Edinburgh conduct.” Un-Edinburgh as synonym for inappropriate!

Even at 10, Sandy can discern the difference between Miss B and another “thrilling teacher, a Miss Lockhart,” who teaches science in the Senior School. Sandy is enthralled by the “lawful glamour” of the science room, and Miss Lockhart’s “rightful place” in it.

Sybil Thorndike was a celebrated English actress. George Bernard Shaw wrote "Saint Joan” specifically for her. Maybe Miss Brodie is thinking of her as she stands “erect, w/ her brown head held high, staring out the window like Joan of Arc as she spoke.”

Poor Sandy. I understand why she feels hurt and puzzled when Miss Brodie chastises her for her exaggerated head-held-high walk. In this photo even Sybil Thorndike looks like she is going too far.—Sarah Shun-lien Bynum

Poor Sandy. I understand why she feels hurt and puzzled when Miss Brodie chastises her for her exaggerated head-held-high walk. In this photo even Sybil Thorndike looks like she is going too far.—Sarah Shun-lien Bynum

Day 1 | October 1

Day 1 | October 1

Ch. 1, pp. 1-11

I read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie when I was 23, before starting my first job as a seventh-grade teacher. The fact that I turned to fiction as a handbook reveals just how ill-equipped I was. I hoped to learn from exemplary models: Goodbye Mr. Chips, To Sir With Love, etc.

I was under the impression that Miss Jean Brodie belonged among the ranks of inspiring educators. Happily, I couldn’t have been more mistaken. One of the novel’s many pleasures is the unsentimental way Spark complicates the trope of the impassioned, quirky, charismatic teacher.

In a novel about six girls and their female teacher, the very first sentence begins with “the boys” as its subject. The boys are nervous, indistinct, interchangeable—there are “three Andrews among the five”—but it’s no accident that they frame our introduction to the girls.

I recognize most of Miss Brodie’s eclectic curriculum but I had to look up “Buchmanites.” They were followers of the American evangelist and religious reformer Frank Buchman. Also known as the Oxford Group, they significantly influenced the creation of AA and its 12-step program.

How swiftly Spark delineates the six girls! Epithets are helpful. Rose, famous for sex. Monica, good at math. Sandy with her little eyes. Jenny the great beauty. Eunice the gymnast. Mary the silent lump. Spark is not afraid of repetition; it serves her crispness and clarity well.

What does it mean to be “famous for sex”? For having lots of it? For being talented at it? I love that Rose doesn’t appear obviously vampy, with her hat “placed quite unobtrusively on her blonde short hair.” I also love the promise that there will be sex in the pages to come.

“There needs must be a leaven in the lump”—a saying that goes back to the Bible and feels newly relevant given our recent obsession with sourdough starters. But the yeast that spreads throughout the dough—should we interpret it as a beneficial influence, or a corrupting one?

Spark’s humor is a source of great delight and mystery for me. What is it about the comic timing of this exchange that makes me laugh out loud? “Who is the greatest Italian painter?” “Leonardo Da Vinci, Miss Brodie.” “That is incorrect. The answer is Giotto, he is my favourite.”

The novel takes place between the wars—a brief interval of peace shadowed by the losses of WWI (as embodied by Hugh, the fallen fiancé). Spark establishes time period neatly: Miss B declares, “This is 1936. The age of chivalry is past.” Direct & unfussy. Again, clarity prevails.

This chapter opens in 1936 and then flashes back to 6 years earlier, when the girls first joined Miss Brodie’s class. Conventional enough. But on the last page, the narration makes an unexpected leap forward to Mary’s death at 23. The handling of time promises to be interesting!

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie invites us into a world that feels heartbreakingly distant right now: a school classroom, filled with young minds and restless bodies and desks and noise and essays on how you spent your summer vacation. At the helm of our classroom is the indelible Miss Brodie, a character of magnificent convictions and questionable judgment who exercises outsized influence on her coterie of handpicked students, with unpredictable results. In this time of pervasive brain fog, I can’t imagine a more bracing antidote than the nimble storytelling and brilliant, funny, incisive sentences of Muriel Spark.

Sarah Shun-lien Bynum is the author of two novels, Madeleine Is Sleeping and Ms. Hempel Chronicles, and most recently a story collection, Likes (FSG). She lives in Los Angeles.

Reading Schedule

Day 1 | October 1: Ch. 1, pp. 1-11

Day 2 | October 2: Ch. 2, pp, 13-26 (through “'That is the order of the great subjects of life, that’s their order of importance.'”)

Day 3 | October 3: Finish Ch. 2, pp. 26-41

Day 4 | October 4: Ch. 3, pp. 43-55 (through “photographing this new Miss Brodie with her little eyes.”)

Day 5 | October 5: Ch. 3, pp. 55-70 (through “with her little pig-like eyes”)

Day 6 | October 6: Finish Ch. 3, pp. 70-78

Day 7 | October 7: Ch. 4, pp. 79-82 (through ““only the squares on the other two sides”)

Day 8 | October 8: Finish Ch. 4, pp. 92-104

Day 9 | October 9: Ch. 5, pp. 105-121

Day 10 | October 10: Ch. 6, pp. 123-137 (The End)

Day 10 | October 10

Ch. 6, pp. 123-137 (The End)

The economy of her method: at the end of Chap 5, physical details like the bicycle boys and the tram-car stop tell us that we’ve completed the temporal lap and arrived back at the novel’s opening scene. An elegant way to re-introduce Joyce Emily in Chap 6

“One of Joyce Emily’s boasts was that her brother at Oxford had gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War.” He would have been among the 4000 Brits, including George Orwell, who joined the anti-Franco forces. See also Colin Firth in “Another Country.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-13937616

Joyce Emily, Mary Macgregor, Miss Brodie: so many sacrifices for such a short novel.

Sandy “wondered to what extent it was Miss Brodie who had developed complications throughout the years, and to what extent it was her own conception of Miss Brodie that had changed.” Good question.

If you wondered in Ch 2 how Sandy’s thoughts on groups/fascisti might relate to her future as a nun, Spark hasn’t forgotten you: "she had entered the Catholic Church, in whose ranks she had found quite a number of Fascists much less agreeable than Miss Brodie.”

“She left the man and took his religion”: Sandy’s difficult love for Miss Brodie leads her to Teddy Lloyd which leads her to Catholicism, a movement that reminds me of Charles Ryder’s journey from Sebastian to Julia to Catholicism in Brideshead Revisited.

“Her mind was as full of his religion as a night sky is full of things visible and invisible.” Spark’s vision of Catholicism begins to emerge as one of vastness, mystery, beauty. A huge & glimmering cosmos that shrinks our human problems down to size.

Sandy, “thinking that it was not the whole story.” Miss B, “trying quite hard to piece together a whole picture.” Resisting wholeness, Spark builds her novel out of catchphrases, snippets, echoes, epithets, bits of poetry & song, flashes forward & back.

Stephen Schiff: “[Spark] lays out the jigsaw pieces over and over…but refuses to cough up the final piece—she trusts her reader to catch on without it. Hence, we finish ‘TPOMJB’ having been told everything about Sandy’s betrayal except why it happens.”

Sandy/Sister Helena clutching the bars of the grille more desperately than ever: what is she yearning to escape? Or hold on to? It’s an image that lingers, full of disturbance and mystery.

Spark in TNY, 5/93: “You have to live with the mystery. That’s the answer in my books."

“There was a Miss Jean Brodie in her prime”: One final repetition, and Sandy’s answer now echoes—almost unbearably—with the accumulation of time and consequences and loss.

Day 9 | October 9

Ch. 5, pp. 105-121

Dierdre Lloyd, alt-version of Scottish womanhood: peasant clothes, languid & long-armed, unbothered & informal. Miss B, Miss Lockhart, Dierdre: studying non-parental adults is such a big part of growing up, a key to figuring out who & how you want to be.

Miss Brodie’s role as Mr Lloyd’s muse is made amusingly literal in one portrait after another (I have a dim memory of this effect being grotesque in the movie), while Dierdre is in the thankless role of artistic helpmeet: “We swathed her in red velvet.”

Any romantic notions I might have had about Teddy Lloyd are shattered by his disgusting wet kiss & vicious words to Sandy. Similarly, any faith I might have had in the integrity or merit of Miss B’s “great love.” Spark disabuses me swiftly & severely.

The cozy bohemian chaos of the Lloyds’ home life—also the dangerous erotic energy circulating between adults and adolescent girls—reminds me of one of my favorite Deborah Eisenberg stories, "The Custodian.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1990/03/12/the-custodian

Spark’s word choices always land just right, managing never to sound contrived or fussy. Miss B “refused him all but her bed-fellowship & her catering”—a very funny but also utterly precise & revealing way of describing the sex & food she provides Mr. L.

As the girls age & grow apart, as Miss Brodie’s schemes further distort her, I begin to miss the earlier chapters’ buoyancy & verve—Paul Lisicky’s lovely term is “comic snap”—I notice more summary & explanation, pieces being moved around the chess board.

But still the explanations dazzle: “she began to sense what went to the makings of Miss Brodie who had elected herself to grace in so particular a way and with more exotic suicidal enchantment than if she had simply taken to drink like other spinsters.”

“They all belong to the Fabian Society & are pacifists”—GB Shaw also belonged to the socialist organization, which advocated for gradual reform & not revolutionary overthrow. Militant Miss B (“gladiator w raised arm & eyes flashing like a sword”) scoffs!

“He had confidence in Miss Lockhart, as everyone did, she not only played golf well and drove a car, she could also blow up the school with her jar of gunpowder and would never dream of doing so.” I love the implication that Miss Brodie very well might.

Day 8 | October 8

Finish Ch. 4, pp. 92-104

Blood tells: Miss B divests this phrase of any pejorative sense, proudly claiming her wild ancestor. “He died cheerfully on a gibbet of his own devising” recalls being hoist with one’s own petard. Either gruesome end could describe Miss B’s downfall.

There’s something plainly witchlike about the excitement and insistence with which Miss Brodie feeds Mr. Lowther. Lobster salad, liver paste sandwiches, cake & tea, porridge & cream. An astonishing array of cholesterol. “You must be fattened up, Gordon.”

She’s also like a fairy tale giant: “Miss Brodie was doing something to an enormous ham prior to putting it into a huge pot.” Their affair seems doomed by incongruities of scale: grand and heroic Miss B, short and slight Mr. Lowther. They don’t fit.

Parul Sehgal: “[Spark] loves reminding us that every word—this phrase, that comma—was brought together by human hands, for your pleasure.” And her characters love discussing word choice, phrasing, etymology, usage: “The word ‘like’ is redundant…”

Spark keeps returning to Mr. Lloyd’s arm for comedy. On him looking romantic: “‘I think it was his having only one arm,’ said Jenny. ‘But he always has only one arm.’ ‘He did more than usual with it,’ said Sandy.” Irreverent Spark never tires of the joke.

Spark does nature sparingly, but she makes it count: “There was a wonderful sunset across the distant sky, reflected in the sea, streaked w blood & puffed w avenging purple & gold as if the end of the world had come without intruding on every-day life.”

At the bottom of p.103, a virtuosic single-sentence paragraph moves us cruelly from elation to disgust. A beautiful, spontaneous expression of youth and freedom—the girls running down the beach—resolves darkly into Miss Brodie’s holiday plans with Hitler.

Though Spark doesn’t make a big fuss over it, I keep noticing how lovely Sandy &Jenny’s friendship is: their closeness & loyalty; their compatibility as co-creators; their holidays spent following the sheep about, full of fresh plans & fondest joy.

Spark’s childhood best friend was named Frances Niven. Here are some lovely archival glimpses of their friendship, as well as the girls’ school and the teacher that inspired the writing of Spark’s novel.

https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=17105

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/muriel-spark-early-writing/

Day 7 | October 7

Ch. 4, pp. 79-82 (through ““only the squares on the other two sides”)

James Wood observes, “In the course of the novel we never leave the school to go home, alone, with Miss Brodie. We surmise that there is something unfulfilled and even desperate about her, but the novelist refuses us access to her interior. This comment surprises me a little because Spark establishes so clearly the nature of her portrait. I would no more expect to go home with Miss Brodie than to overhear the inner thoughts of Jay Gatsby. To me the very title betokens myth, not interiority.

I don’t know which repetition makes me more sad: Mary Macgregor running hither and thither in the science room, terrified by the magnesium flares; or Miss Lockhart, quite the nicest teacher in the school, already feeling exasperation at Mary’s dull face.

In another tidy origami fold of future time, Spark compares Sandy’s regret regarding Mary with Miss Brodie’s. While Sandy suggests that fate/divine authority may be punishing her for her unkindness, Miss B’s regret takes the form of worldly suspicions.

Miss Mackay’s plot is deliciously foiled by Mary’s sheer denseness & two years of Miss Brodie’s indoctrination regarding the evils of team spirit. Her stirring celebrations of “individualism” serve a fascistic desire to maintain control over her own team

“[Jenny] did not again experience her early sense of erotic wonder in life until suddenly one day when she was nearly forty, an actress of moderate reputation married to a theatrical manager.” I find this statement quietly devastating on two levels.

First is the sad fact that Jenny goes for nearly 30 years without feeling “that same buoyant and airy discovery of sex,” & when she finally does in Rome (a city beloved by Miss B), she can’t act on it: “there was nothing whatever to be done about it.”

Second is the flat and nearly dismissive description of Jenny’s professional life—yet she really did become an actress! So what she’s not Sybil Thorndike. She has dedicated herself to a vocation & made a life out of it. The narrator seems unimpressed.

Consoling, though, is the gentle, expansive note on which Spark ends Jenny’s flash-forward: “the concise happening filled her with astonishment whenever it came to mind in later days, and with a sense of the hidden possibilities in all things.”

“She was by temperament suited only to the Roman Catholic Church; possibly it could have embraced, even while it disciplined, her soaring and diving spirit, it might even have normalised her.” It’s tempting to read this as a gloss on Spark’s conversion.

“A creeping vision of disorder”: is this what Sandy experiences as a result of Miss Brodie’s influence and selective amorality? I wonder if this uneasiness compels Sandy toward Catholicism—does it restore her sense of order, renew her “moral perception”?

Day 6 | October 6

Finish Ch. 3, pp. 70-78

The transfiguring power of the incongruous adverb: “Jenny, out walking alone, was accosted by a man joyfully exposing himself beside the Water of Leith.” Even on the subject of flashers, we can expect Spark to say the unexpected

“‘Nasty’ or ‘nesty’?” Why does this pronunciation provoke Sandy’s revulsion? Is it too provincial & Scottish-sounding, lacking the elegant English vowels for which she is famous? Or does she associate ‘nesty’ w/ nests, eggs, the icky end product of sex?

“‘Nasty’ or ‘nesty’?” Why does this pronunciation provoke Sandy’s revulsion? Is it too provincial & Scottish-sounding, lacking the elegant English vowels for which she is famous? Or does she associate ‘nesty’ w/ nests, eggs, the icky end product of sex?At 11, my daughter also developed a strong dislike for the word “nasty” (especially how her classmates pronounced it: “naaaahsty”). The other word she despised the sound of was “cohort.” Now “nasty” feels inseparable from Trump’s misogynistic use of it.

Sandy’s ongoing fantasies about the “wonderful policewoman” (Sgt. Anne Grey—a delightfully sober name bestowed by Sandy) further encourage me to read her character through a queer lens. A pattern is emerging, esp. as revealed via Sandy’s inner life.

“Alan Breck clapped her shoulder and said, ‘Sandy, you are a brave lass’” VS “Sgt. Anne pressed Sandy’s hand in gratitude; and they looked into each other’s eyes, their mutual understanding too deep for words.” A semicolon lets us linger on their touch.

See also: Sandy & the Lady of Shalott; Sandy’s rapturous description of Miss Lockhart & the science room; Sandy wondering “if Jenny, too, had the feeling of leading a double life, fraught with problems that even a millionaire did not have to face.”

Even in her fantasy world, Sandy still wears her hat in the same way she does at school: “So Sandy pushed her dark blue police force cap to the back of her head.” The commingling of fantasy and reality is a tendency in both Miss Brodie and her girls.

“We’ve got to find out more about the case of Brodie.” The real heart of the investigation is not what Miss Brodie is doing with Lowther/Lloyd/Rose but how Sandy feels about it; she’s grasping at “something,” trying to “work out her reasons.” Repeatedly.

They placed Miss Brodie on the lofty lion’s back of Arthur’s Seat, with only the sky for roof & bracken for a bed.” Arthur’s Seat is an ancient volcano, which makes the girls’ chosen location for Miss B & Mr. L’s sexual intercourse all the funnier to me

Day 5 | October 5

Day 5 | October 5Ch. 3, pp. 55-70 (through “with her little pig-like eyes”)

Spark in The New Yorker, 5/93: “Well, suspense isn’t just holding it back from the reader. Suspense is created even more by telling people what’s going to happen. Because they want to know how. Wanting to know what happened is not so strong as wanting to know how.”

A sympathetic detail: Miss Brodie sagging gratefully against the door once she’s within the safety of her own classroom, having run the gauntlet of the Junior school corridors. Maintaining aloofness & superiority with scornful colleagues can take a toll.

p57-58: “Monica’s anger” to “past my prime.” In less than a page, we flit effortlessly through FIVE distinct time periods: the girls in ’31; Rose at 16; Monica in late 50s; Sandy & Miss B at tea; the moment (?) when Sandy learns Lloyd really did kiss.

Miss B, diminished: in another flash-forward to after the war, the sight of her “shrivelled & betrayed” in her musquash coat so unsettles me that I want to look away and stare at the hills, like Sandy. Her cancer & early death leave me curiously cold here.

Teachers need epithets too. Mr. Lowther, shy and short-legged; Mr. Lloyd, golden-locked and one-armed. And Miss Gaunt? Gaunt. Did Spark really just do that? She is so punk rock. Short, fast, brutal, irreverent, gleefully repeating the same three chords.

Just in case you might have been wondering who betrayed Miss Brodie, Spark quickly destroys that conventional source of suspense. And does so in a typically nonchalant manner: “It is seven years, thought Sandy, since I betrayed this tiresome woman.”

Thomas Mallon: “When Spark inclines to greater intimacy, it is not toward the character but toward the reader.” The casual mention of Sandy’s betrayal makes us privy to information that only Sandy and the omniscient narrator possess; it’s our three-way secret.

It’s difficult for me to resist Miss Brodie in those moments when she gives voice to my own prejudices in such a commonsensical & amusing way: her dismay, for instance, that Eunice “was taking a suspiciously healthy interest in international sport.”

Day 4 | October 4

Ch. 3, pp. 43-55 (through “photographing this new Miss Brodie with her little eyes.”)

Chapter 3 begins: "The days passed and the wind blew from the Forth.” The omniscient narrator is clearing her throat—wryly invoking the forces of time and weather—as a prelude to the sweeping commentary on history and society she’s about to entertain us with.

Her own kind: A lively sociological portrait of “progressive spinsters of Edinburgh” clarifies that Miss Brodie’s attitudes and enthusiasms were by no means unusual in the 30s. The Schlegel sisters from Howard’s End: possible forebears to these vigorous women?

Nothing outwardly odd about Miss B, but “Inwardly was a different matter, and it remained to be seen, towards what extremities her nature worked her.” How and in what direction will her fluctuating nature grow? Therein lies the suspense. No need to conceal plot.

At the start of the new term, headmistress Miss Mackay gives a rushed speech to Miss B’s class, saying several of the exact same things she said the year before. “Education factory” now seems a fair assessment. When to trust Miss B’s opinions, and when not to?

The Brodie set on Mr. Lloyd, the art master: “Most wonderful of all, he had only one arm, the right, with which he painted. The other was a sleeve tucked into his pocket. He had lost the contents of the sleeve in the Great War.” Spark commits fully to the little girls’ perspective. The Great War is an abstraction to them, remote & unimaginable—they regard the amputated arm with solemn delight. Which then gives me permission to laugh at the careful, dignified tone of that last sentence.

I love the freedom with which Spark creates compound words. My favorite today is “sex-wits.” At one end of the sex spectrum is witless Mary, at the other end is Rose, all instinct and no curiosity: in between is Sandy and Jenny, endlessly fascinated and mystified.

I so recognize from my own childhood Sandy’s impulse to perform for her friends—the irresistible high of hamming it up, even as with each repetition the performance grows more broad & ridiculous & manic—“a state of extreme flourish.” See Maya in PEN15.

Day 3 | October 3

Finish Ch. 2, pp. 26-41

Another bold flash-forward, starring Eunice the gymnast: we leap ahead to 1949, when the Edinburgh Festival was still new. It was founded in 1947 to provide “a platform for the flowering of the human spirit” in the aftermath of WW2. Miss B would approve.

Major revelations in the flash-forward: Miss B’s premature death, forced retirement, and betrayal by one of her girls. Dramatic twists that many novelists would guard jealously. What does Spark gain by disclosing this information so lightly, so early on?

“They approached the Old Town which none of the girls had properly seen before, because none of their parents was so historically minded as to be moved to conduct their young into the reeking network of slums which the Old Town constituted in those years.”

“Now they were in a great square, the Grassmarket, with the Castle, which was in any case everywhere, rearing between the big gap in the houses where the aristocracy used to live.”

“Now they were in a great square, the Grassmarket, with the Castle, which was in any case everywhere, rearing between the big gap in the houses where the aristocracy used to live.” “Then the group-fright seized her”: Sandy’s neologism perfectly captures the psychology that keeps her in thrall to Miss Brodie & a member of the Brodie set even as her misgivings mount. Her insight about Miss B’s jealousy of “rival fascisti” is spot-on.

“Then the group-fright seized her”: Sandy’s neologism perfectly captures the psychology that keeps her in thrall to Miss Brodie & a member of the Brodie set even as her misgivings mount. Her insight about Miss B’s jealousy of “rival fascisti” is spot-on.Our third flight into the future & maybe the most amazing so far: we meet Sandy in her middle age & she is now Sister Helena! A girl raised in a city of Presbyterians, in a “believing but not church-going” family. Spark too became a Catholic as an adult.

It seems fitting that Sandy, with her talent for transforming the boredom of a long walk into an ardent conversation with Alan Breck of Kidnapped, should one day write a treatise called “The Transfiguration of the Commonplace.”

A further refinement of what Edinburgh signifies: “We of Edinburgh owe a lot to the French. We are Europeans.” Edinburgh = pragmatic, respectable, but also cosmopolitan, continental? Maybe the city is as rich in contradictions as Miss Brodie herself.

On the subject of contradiction, here’s Spark on the word nevertheless: “It is my own instinct to associate the word, as the core of a thought-pattern, with Edinburgh particularly…The sound was roughly ‘niverthelace’ & the emphasis was a heartfelt one.”

More from Spark: “I believe myself to be fairly indoctrinated by the habit of thought which calls for this word…I find that much of my literary composition is based on the nevertheless idea.” I’m going to hold nevertheless in my mind as we keep reading.

“A very long queue of men…Monica whispered, ‘They are the Idle.’” A sobering glimpse of UK’s struggling economy in the 20s & 30s: the Depression hit northern England & central Scotland particularly hard. See Orwell’s “The Road to Wigan Pier” for more.

Miss Brodie on the Unemployed: “Sometimes they go and spend their dole on drink before they go home, and their children starve. They are our brothers. Sandy, stop staring at once. In Italy the Unemployment problem has been solved."

A typical Brodie hodgepodge, hilarious for its lack of transitions: Moral superiority! Compassionate egalitarianism! Mind your manners! Hooray for Mussolini’s regime!

Day 2 | October 2

Ch. 2, pp, 13-26 (through “'That is the order of the great subjects of life, that’s their order of importance.'”)

Chap 2 begins with the girl whose death was just introduced so suddenly: hapless and lumpy Mary Macgregor. Spark remains unsparing (even as an adult Mary “was clumsy and incompetent”) yet she also creates an understated sense of pathos with this character.

The Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was founded during WWI: “Join the Wrens today and free a man to join the Fleet.” The WRNS reached its largest size in 1944, with 74,000 women doing over 200 different jobs. Mary was clumsy but she answered the call.

“She ran one way; then, turning, the other way; and at either end the blast furnace of the fire met her. She heard no screams, for the roar of the fire drowned the screams; she gave no scream, for the smoke was choking her.”

Brilliance at the sentence level: Spark uses short phrases, strong punctuation (semi-colons most notably), and repetition (parallel syntax, the tripling of “scream”) to capture Mary’s bewildered back-and-forth movement along the smoke-filled hotel corridor.

As quickly as we leapt ahead, we return to the past—without even a paragraph break. In one sentence Mary stumbles and dies; in the very next she is ten again, “sitting blankly among Miss Brodie’s pupils.” The abrupt shift, the juxtaposition: strangely poignant.

“One-armed Mr. Lloyd, in his solemnity, striding into school”—his missing arm is yet another loss from WW1, and how jarring to encounter it right on the heels of the girls’ uproarious imaginings: Mr. Lloyd committing sex with his wife while wearing pyjamas!

Edinburgh, the novel suggests, is more than just a city: it’s an entire way of being. Sandy is embarrassed by how her English mother differs from “the mothers of Edinburgh” in their practical tweed or musquash (apparently muskrat fur is long-lasting).

The overheated prose in Sandy and Jenny’s masterpiece, “The Mountain Eyrie,” is a wonderful piece of comedy, but in its midst is a small, wistful detail. When little pig-eyed Sandy describes her fictional alter ego, she writes “her large eyes flashed.” If only!

The omniscient narrator gets quite close to Sandy’s thoughts in these pages. We see her sensitivity, her secret ferocity, the richness of her 10-year-old imagination. We also see the conflict between her internal and external worlds: Miss B misunderstands her.

My favorite moment of Sandy’s interiority: “The evening paper rattle-snaked its way through the letter box and there was suddenly a six-o’clock feeling in the house.” How do you interpret Sandy’s six o’clock feeling? To me it feels bleakly soul-dampening.

Creepy behavior from the singing teacher, Mr. Lowther, with a tacit OK from Miss B: “He twitched [Jenny’s] ringlets…as if testing Miss Brodie to see if she were at all willing to conspire in his un-Edinburgh conduct.” Un-Edinburgh as synonym for inappropriate!

Even at 10, Sandy can discern the difference between Miss B and another “thrilling teacher, a Miss Lockhart,” who teaches science in the Senior School. Sandy is enthralled by the “lawful glamour” of the science room, and Miss Lockhart’s “rightful place” in it.

Sybil Thorndike was a celebrated English actress. George Bernard Shaw wrote "Saint Joan” specifically for her. Maybe Miss Brodie is thinking of her as she stands “erect, w/ her brown head held high, staring out the window like Joan of Arc as she spoke.”

Day 1 | October 1

Day 1 | October 1Ch. 1, pp. 1-11

I read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie when I was 23, before starting my first job as a seventh-grade teacher. The fact that I turned to fiction as a handbook reveals just how ill-equipped I was. I hoped to learn from exemplary models: Goodbye Mr. Chips, To Sir With Love, etc.

I was under the impression that Miss Jean Brodie belonged among the ranks of inspiring educators. Happily, I couldn’t have been more mistaken. One of the novel’s many pleasures is the unsentimental way Spark complicates the trope of the impassioned, quirky, charismatic teacher.

In a novel about six girls and their female teacher, the very first sentence begins with “the boys” as its subject. The boys are nervous, indistinct, interchangeable—there are “three Andrews among the five”—but it’s no accident that they frame our introduction to the girls.

I recognize most of Miss Brodie’s eclectic curriculum but I had to look up “Buchmanites.” They were followers of the American evangelist and religious reformer Frank Buchman. Also known as the Oxford Group, they significantly influenced the creation of AA and its 12-step program.

How swiftly Spark delineates the six girls! Epithets are helpful. Rose, famous for sex. Monica, good at math. Sandy with her little eyes. Jenny the great beauty. Eunice the gymnast. Mary the silent lump. Spark is not afraid of repetition; it serves her crispness and clarity well.

What does it mean to be “famous for sex”? For having lots of it? For being talented at it? I love that Rose doesn’t appear obviously vampy, with her hat “placed quite unobtrusively on her blonde short hair.” I also love the promise that there will be sex in the pages to come.

“There needs must be a leaven in the lump”—a saying that goes back to the Bible and feels newly relevant given our recent obsession with sourdough starters. But the yeast that spreads throughout the dough—should we interpret it as a beneficial influence, or a corrupting one?

Spark’s humor is a source of great delight and mystery for me. What is it about the comic timing of this exchange that makes me laugh out loud? “Who is the greatest Italian painter?” “Leonardo Da Vinci, Miss Brodie.” “That is incorrect. The answer is Giotto, he is my favourite.”

The novel takes place between the wars—a brief interval of peace shadowed by the losses of WWI (as embodied by Hugh, the fallen fiancé). Spark establishes time period neatly: Miss B declares, “This is 1936. The age of chivalry is past.” Direct & unfussy. Again, clarity prevails.

This chapter opens in 1936 and then flashes back to 6 years earlier, when the girls first joined Miss Brodie’s class. Conventional enough. But on the last page, the narration makes an unexpected leap forward to Mary’s death at 23. The handling of time promises to be interesting!

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

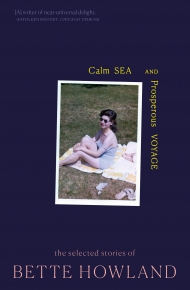

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.