On Irrelevance: Part I

• Mary-Beth Hughes • October 1, 2013

To call writing relevant or irrelevant seems to indicate that there is a hierarchy of things: certain moments (in many advocates for relevance this time is our very own time—the present moment) are more important than other moments in history; certain places or people need more attention than others. A writer could become irrelevant, like Shen Congwen (APS10), when he writes not about the class struggle but a love story between an orphan girl and a local military officer, but is relevance just another way of confining writers and their work according to one's limited position in time and space?

Earlier in the year, while we were working on Shen Congwen’s letters, a writer who was accused of irrelevance in his time, this article came out. Which got us thinking about what makes a story or a novel or a poem relevant; we asked some APS contributors to recommend a favorite irrelevant writer.

Around Halloween, I packed up my mother’s books and brought them home. She was a committed public library patron, so I’d love to know the books she liked enough to buy and keep, what she saved to go back to. But before I unpack boxes, I’m looking to my own shelves to remember some of what’s been essential to me. This week I’m reading Lisa Shea and Grace Paley.

From Grace Paley’s “The Immigrant Story”:

...In America, in New York City, he lived a hard but hopeful life... Mostly he put his money away for the day he could bring his wife and sons to this place. Meanwhile, in Poland famine struck. Not hunger which all Americans suffer six, seven times a day but Famine which tells the body to consume itself. First the fat, then the meat, the muscle, then the blood. Famine ate up the bodies of the little boys pretty quickly. My father met my mother at the boat. He looked at her face, her hands. There was no baby in her arms, no children dragging at her skirt. She was not wearing her hair in two long braids. There was a kerchief over a dark wiry wig. She had shaved her head like a backward Orthodox bride, though they had been serious advanced socialists like most of the youth of their town. He took her by the hand and brought her home. They never went anywhere alone, except to work or the grocer’s. They held each other’s hand when they sat down at the table, even at breakfast. Sometimes he patted her hand, sometimes she patted his. He read the paper to her every night.

They are sitting at the edge of their chairs. He’s leaning forward reading to her in that old bulb light. Sometimes she smiles just a little. Then he puts the paper down and takes both her hands in his as though they needed warmth. He continues to read. Just beyond the table and their heads, there is the darkness of the kitchen, the bedroom, the dining room, the shadowy darkness where as a child I ate my supper, did my homework and went to bed.

From Lisa Shea’s Hula:

“You’re dead, soldier,” he says. I pretend I don’t have any arms or legs or a head.

My mother says something happened to our father in the war but my sister says he is just mean. In the back of his head is a hole where no hair grows. In the sun, light strikes the metal plate like signals from a flying saucer.

Sometimes, our father hits his head with his fists. Once, my sister and I hit our heads and we both saw stars. Other times he chases us up the stairs with his rope belt. By the time we get to the top, our legs are burning hot.

Our mother used to be a dancer. She taught the conga, tango, rumba, mambo, and cha-cha. She also taught the hula, the limbo, the dance of the seven veils. Now she works in a room above the studio, making costumes for the shows they put on.

When she met our father, she was dressed like a hula girl at a luau party and he was in charge of roasting the pig. She says our father’s eyes were angry and blue and when he watched her hula, that was the end of her.

Back to Top

Author

Mary-Beth Hughes is the author of the novel Wavemaker II (Atlantic Monthly Press) and a collection of stories, Double Happiness (Grove Press/Black Cat).

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

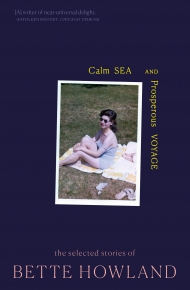

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.