Monday Memo

News • November 5, 2018

Writer's Water Bottle, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Kangxi period (1662–1722), China; at the Met

This week at A Public Space, we're talking about why we make art:

- "The human situation is beautiful and strange. We are in fact Gilgamesh and Oedipus and Lear. We have achieved this amazing levitation out of animal circumstance by climbing our rope of sand, insight and error and corrective thought and persisting error. The working of the mind is astonishing, and beautiful. I remember two lines from a poem I learned in high school: "Let not young souls be smothered out before / They do strange deeds and fully flaunt their pride." That poem protested poverty, as I recall. But privilege can smother, too. And the best education can smother, if the burden of it is to tell the young that they need not bother being young, to distract them from discovering the pleasures of their own brilliance, and to persuade them that basic humanity is an experience closed to them." –– Marilynne Robinson, APS No. 1

- "I believe in the elaborate taking care of others. And we live in a culture where 'I'm not my brother's keeper,' 'That's your responsibility,' 'Get a life' have become bywords, code phrases, anthems for elaborate indifference, selfishness, greediness, and the failure of empathetic acceptance. In the same way that we need to repair the economy, we need to repair the effects of an economy of selfishness. And that isn't just the filling in of the big bucks that have fallen out of the system. The rescue that we need is emotional rescue, communicative, large-hearted. I've always dreamed that people listening to the show would hear that readers and writers are expanders of feeling centers, of the global ability to imagine other lives. And I want people listening to the show, yes, of course, to grasp its intelligence, but to also hear that it wants to show the feeling that reading and imagination inspire in writers and readers. We want to share those things with listeners. There are all sorts of other things that you get on radio and television, but I wanted listeners of Bookworm to hear words, ideas, but particularly emotions that don't get discussed in public if at all elsewhere. That is to say, for one reason or another, the show is a crusade that's much larger than the subject of books." –– Michael Silverblatt, O Magazine

- "I should also say, nobody's on any of our backs, saying, Hey kid, make that work. I mean, nobody gives a shit. You know that. So I think if you don't have any enduring passion within yourself for the work you're going to be doing, why do it. I find that commitment very prevalent in the past. The religious conviction is an interesting phenomenon that we no longer share in. But I think you can get an idea of how painting was an extension, I suppose, of that kind of conviction. I don't know how many of you have recently seen the Rothko and the Pollock show. But I was struck with how impossible it was for me to deny the validity of any of that work, both Rothko and Pollock. I didn't have to like them, but there was a –– I was going to say quality, but that's a difficult word, but there was something that one couldn't deny. You couldn't turn your back on that work." –– Michael Goldberg, APS No. 25

- "Most of us, given a choice between chaos and naming, between catastrophe and cliché, would choose naming. Most of us see this as a zero sum game—as if there were no third place to be: something without a name is commonly thought not to exist. And here is where we can discern the benevolence of translation. Translation is a practice, a strategy, or what Hölderlin calls 'a salutary gymnastics of the mind,' that does seem to give us a third place to be. In the presence of a word that stops itself, in that silence, one has the feeling that something has passed us and kept going, that some possibility has got free." –– Anne Carson, APS No. 7

- "My mother had gone to visit someone in a village near Paris. The apartment was high up, and since I was too little to look down into the street I could see nothing from the window but the rooftops of the surrounding houses and a large piece of sky. We spent much of the day there, but I noticed nothing; I was too charmed by the many wonderful airs someone was playing on a wooden flute. The sound came from a high garret and a remote one too, for my mother could hardly hear it. My own hearing must have been more acute, because I didn't miss a quaver from the little instrument, and I was spellbound. [...] There, for the first time, I vaguely sensed the harmony of external things, my soul being equally ravished by the music and the beauty of the sky. " –– from George Sand's My Life, discussed in Alexander Chee's master class on the topic of forming our identities in life and in art, which took place this past weekend here at A Public Space

Back to Top

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

Featured Title

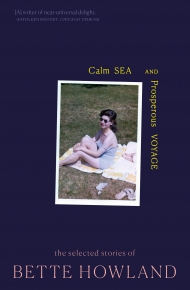

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.