On the Fictional Self: An Interview with Sara Majka

• A. N. Devers • February 16, 2016

A. N. Devers talks with debut author Sara Majka about the Wu-Tang Clan, Alice Munro, and the intimacy of fiction. Cities I’ve Never Lived In: Stories by Sara Majka, is the newest A Public Space Book, with Graywolf Press.

AD: In your title story, "Cities I've Never Lived In" your narrator decides to get on a bus and travel across the country, serving food at and then eating food in homeless shelters. I remember a few years ago you took a bus trip across the country; did you also serve food in shelters? Did you know you might write about your experience?

SM: I did get on a bus and travel the interior cities, much of them rust belt cities, for two months. Before that I had volunteered at soup kitchens for a little bit, and during the trip I ate at times in soup kitchens. So that story is quite autobiographical. Actually I think that story is all true, which isn't the case with the rest of the collection. That story was written more as an essay, but since it was the same character and same situation as the other stories, it felt a piece with the collection.

It gets tricky trying to explain it, what part of your life you use for stories and what part you don't, and also how you make sense of it. On that trip, in real life, I also met members of Wu-Tang on the train and they invited me to travel to Chicago with them. No one famous—they were periphery members, maybe some people who do the booking. I also met a really wonderful guy on that trip. Incidentally, this guy told me he once had a girlfriend who had also been invited to travel with members of Wu-Tang. I said to him, how many members of Wu-Tang are there? All this could be a story (one could argue a better story), but it wasn't meant as part of this book.

AD: That is another story! But, I must know, did you end up traveling to Chicago with Wu-Tang?

SM: No, and a part of me was thinking, I should really do this and just see, but I didn't want to. I was heading to Buffalo and felt that I should go there—it was late at night and I had a taxi waiting for me and the word Buffalo had come to seem important. But also, there was talk with Wu-Tang about the party van that would pick us up, and then the hotel we would go to, and I felt agreeing in some way would show a romantic interest that I didn't have.

AD: That sounds sensible. Do you think the remarkable nature of coincidence is difficult to convey in autobiographical fiction?

I’ve never thought of it that way, but, yes, I think I don't use coincidence. When I go on a trip that in some way has an imaginary role for me, it feels like I set up a series of moments that I know will already be there. The coincidental elements don't seem to resonate in the same way, even if, on the surface, they sound like the more exciting story.

AD: How did you choose fiction as your narrative vehicle?

SM: I was very shy growing up and we moved a lot. I read novels all the time—on the school bus, before gym class, really any free moment, and then I also wrote in a journal. When I was young I only imagined that one could write novels, and so I wanted to write one of those. I only considered fiction at that age and never outgrew that idea.

AD: Which childhood novels and books did you fall in love with? Was there a specific one or few that you still feel close to, and identify with establishing this desire?

SM: Early on I remember The Secret Garden. Oh, Where the Red Fern Grows. That book killed me, absolutely killed me. I also read Paddington Bear, Nancy Drew, The Baby-Sitters Club, and Encyclopedia Brown…

When I was older, no one in my family was a reader at that time, but my mom would take me to the library and I would take out any book that I recognized the title or author. And also my dad had a box of books in the garage from his private school days and I would venture out there and pull stuff out that looked familiar to me. He had Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, so I sat up alone in my bedroom as a kid trying to make sense of it.

AD: Do you look back at your childhood journals? And do you still journal?

SM: I've started on the project of shredding them. I know this has been written about before—what to do with one's childhood journals. It felt like too much to keep moving with those boxes, and it felt like a past that I didn't need to hold onto anymore. A lot of the stuff was sad. I was lonely in school growing up. I wrote poems, too, and I would compile the ones I liked best in another notebook, so I kept things like that. And the journal from when I met the man that I married (I'm divorced now), I kept that.

I don't journal like that anymore. I stopped maybe five years ago? Though I'll still go through periods when I do it.

AD: It pains me to think of you shredding your journals. Particularly because I’ve just finished the Ferrante Quartet and in one of the books there is a scene where a woman gives her childhood journals to her best friend for safekeeping in her adulthood, because she is afraid her husband will discover them, and because they weigh on her, as you describe. Then the childhood friend reads them and they anger her, and she destroys them herself. This anecdote doesn’t help my case for their survival, I suppose, but I would gladly store them for you, and promise to not read them and not destroy them. Any chance you’ve read the Ferrante Quartet?

SM: I promise you that we’re better off with these journals recycled.

I’ve started the Ferrante, but only just started. I haven’t read such a traditional style of storytelling in quite some time.

AD: Absolutely read it all. The story becomes more untraditional, and seemingly autobiographical, as the story progresses. Do you consider your work autobiographical fiction? Have you read other autobiographical fiction before writing your own?

SM: I read lots of autobiographical fiction. I wrote an essay for Catapult about that and tried to guess at why it's so important to me. I use my internal world when writing, and I consider myself in that vein, but so much of it, almost all of it, is made up.

AD: Besides Knausgaard, who you describe serving breakfast in your Catapult piece, after you have seen him speak the night before, who are some writers doing autobiographical fiction that are interesting to you right now? If you had to build a library of five books to recommend to people who were new to the concept of autobiographical fiction, what would they be?

SM: Sebald, Knausgaard, Ben Lerner, Amy Hempel's Reasons to Live, Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son, The Things They Carried. But I don't think of it as a separate category—I don't care whether it's actually autobiographical or not, but I like books that have a large degree of intimacy with the actual writer of the book. Someone like Thomas Bernhard. And I don't mean loving intimacy, I just mean intimacy. And then someone like Alice Munro, who even has a character complain about writers who have an event happen to them and thinly disguise it when writing it up (I forget what story this is from), she uses her mind throughout her stories, and then ventured fully into the form in The View from Castle Rock, so it's interesting to look at what that meant for her.

AD: You are teaching a course with Catapult called Writing Out of Desperation. Your narrator in many of these stories describes being close to falling part, about feeling desperate, about being close to or behind a breakdown. What does it mean to be writing out of desperation for you?

SM: I feel like a one-issue candidate sometimes when I talk about writing, in that I'm against talking about it in terms of craft, like it's something that's composed of pieces that can be worked on and improved. Writing out of desperation was probably my latest way of phrasing it. I started writing really young. As I said, I was shy and we moved a lot, and the rest of my family was not introverted in the way that I was, and I have always needed it. Anyways, I was a journaler and I'm sure not a very good writer, but it was necessary. So you get older and somehow publish a book and it's out there and there are reviews and ... but writing still comes from that place.

AD: And how do you think you write desperation into your fiction without it sounding, well, desperate?

SM: Well, a New Englander's desperation is going to be so restrained and private that it's not going to be very ... desperate-seeming. Even if it is in your heart, really, really desperate. I find that contrast interesting, and that's probably how it balanced out in the book. I just now came up with the phrase "the self-inflicted dignity of these people" and I like that.

AD: I would say that “self-inflicted dignity” you describe allows you access to unique descriptive powers. In your story “Miniatures” your narrator begins to cry, and she says, “It became difficult to drive because there was water in my eyes, and my nose was running.” Did it occur to you to avoid using the word crying?

SM: I have half a guess that I used “crying” and an editor cut it out. But perhaps I didn’t. If I didn’t, then I was just using the language of that character, and as she was imagining her childhood, she would have stuck to concrete, simple phrases like the ones used. Or maybe it’s a little dissociative and that’s why I wrote it like I did.

AD: What is the role of travel in your life, and what importance does it play in your fiction?

SM: I feel most at peace when I travel. It worked out in the end that I traveled on my own, and I liked to slip through the world that way. It's amazing how much you can just walk through, if it's just you walking in a way that takes up very little space. I'm not sure the importance it has in my fiction. As I answer this, I'm in some way working to recall, as my life has changed so much in the past year and a half. I bought an apartment in Queens and also had a baby. I'm afraid my answers aren't true in the way they should be. But I'm trying to remember what it used to feel like. Now I walk around in Queens, going in and out of small shops, which is much like travel. I found a Romanian meat market the other day.

AD: We are both new mothers, you very new, and now I have a toddler. We conducted this interview by catching moments, between our children’s naps, between appointments, while traveling, and it is a completely different life for both of us compared to when we were in graduate school together. Even though your son is only a few months old, do you have any thoughts about being a working writer and mother? I have found it difficult, and look back at my time before and see so much of my use of writing time as indulgent and wasted. Any thoughts on this or thoughts to pass along to writers in the same boat?

SM: Oh god, none. It’s been too busy for thoughts. I’m a single mom, which I like to make a note of, as if I can become an advocate of it. And as I told you, I thought I could get him to take a long nap today so we could do this, but then they started drilling the (shit) out of the street in front of my apartment. It sounds like they’re drilling my apartment.

You need a lot of wasted time and indulgency in order to write well. That’s my feel of it. I don’t have that now. But I am trying to concoct a plan that might allow for that in another few months. It involves maybe selling my apartment and moving to a place where we can live off those proceeds. Live off very little. I guess that’s my largest advice to writers who don’t come from means: to learn to live off as little as you can. But then one wants things in life. For instance, in my late thirties, I wanted a child. I wanted an apartment and a little stability. I wanted to live in New York City. It becomes a matter of sorting through your wants.

Buy your copy of Cities I've Never Lived In at your local independent bookstore or order one online today.

Back to Top

Author

A. N. Devers is a writer and contributing editor at Longreads.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

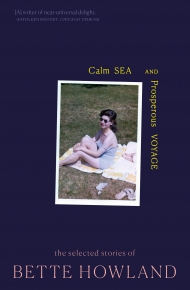

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.