A Letter from Leslie Jamison

• Leslie Jamison • October 23, 2014

I’m sitting in Slottsparken, in Oslo—on the stone steps in front of the Royal Palace, in the shadow of a looming bronze king on his looming bronze horse—and I’m thinking about public spaces, how they summon an inadvertent gathering stripped of intention or annotation: a young artist in Converse high-tops holds a baguette in one hand and a splattered canvas in the other; an elderly couple strides by in matching sunglasses, still holding hands after however-many years; a group of children convulses collectively around the fact of a tiny toffee-colored dog; a woman bends over to reach her arm down into a garbage can.

Public spaces gather individual stories into passing relation, and A Public Space gives us glimpses into these private infinities, the engines of desire and fear that might drive them. A Public Space notices the world—in all of its particulars, their odd collection—and delivers this world to us. It makes room for joy—that little toffee dog!—and perpetuity—those sunglasses, those gripping hands. It makes room for strangers and mysteries and necessity; it’s not afraid to include the woman who sticks her hand into the trash. In one recent issue, Ander Monson speculates: “perhaps it’s not too late to rehabilitate your heart, the echo chamber of your voice,” and I think it’s fair to say A Public Space has become a recurring echo chamber: each issue conducting a collection of voices into chorus.

It feels right to write about A Public Space far away from its home on Dean Street, in Brooklyn, because it has always loved roaming far and wide. In its pages you’ll find a Zimbabwean coffin maker and a makeshift outdoor gym in Beijing, a Buenos Aires neighborhood with streets named after famous women, and a glossary of Antarctica slang. (Degomble: to shake the hardened snow from one’s hair).

My own history with A Public Space began in 2006, when I was temping at a large bank in midtown Manhattan—a windowless room full of cubicles, a decidedly un-public space—and the magazine decided to publish one of my stories. It was my first publication anywhere. Hearing that someone actually liked my writing enough to publish it was like a sudden swell of wind. It gave me faith in something beyond the cubicle.

One of the most singular and spectacular things about A Public Space has always its commitment to unknown authors: almost every issue introduces someone who has never been in print. It’s a magazine committed to discovery: to discovering new voices, new places, new layers of feeling and experience.

Years later, under the northern sun of Oslo, far from those dim Midtown cubicles, I’m writing these words to you—you, who are probably a stranger to me, unless you are my mother, who has been a faithful subscriber to A Public Space since 2006 (hi mom!). I’m sitting in a park full of infinite human lives and thinking about communities of readers and writers as public spaces of another kind, and I’m thinking that perhaps, if you have read some of the same words as I, you are not entirely a stranger after all.

It’s precisely this kinship—faceless but not soulless, this kinship of bodies turning the pages and hearts receiving them—that A Public Space has made possible for the past eight years.

With your support, we can keep dwelling in this kind of public space for years to come. Please think about helping to make it possible.

Thank you,

Leslie Jamison

P.S. Contributions at any level help to make A Public Space possible, but if you’re able to make a donation at the $100 level, you’ll receive a signed copy of Issue 3, with Leslie Jamison’s debut story, “Quiet Men.” Donors at the $250 level will also receive a signed copy of her essay collection, The Empathy Exams, which received the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize and was a New York Times best seller this year. CLICK HERE TO DONATE.

Thank you for being a part of A Public Space.

Back to Top

Author

Leslie Jamison is the author of the novel The Gin Closet (Free Press) and the essay collection, The Empathy Exams, which received the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize. She lives in New York City.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

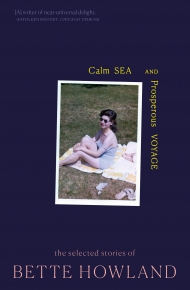

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.