I’m Bulgarian, which is to say a fatalist

• APS | 7 Questions for Miroslav Penkov • October 1, 2013

1. Can you describe your daily routine, any rituals or habits?

It’s general consensus that a writer ought to write, or at least put in the hours behind the typewriter, every day.

I’ve never been able to write every day. Nor do I think I’ll ever manage to. Sometimes I’ll write five, six, ten days in a row. Other times, a week goes by without new words. I tell myself that’s fine, as long as I keep turning the new story over in my mind, like concrete in a lorry.

I write in the afternoon, or late at night, or whenever there is time in between. But never in the morning. The morning is a savage time to me. When the sun passes its apex, I take some instant coffee - a couple spoonfuls in a little cold water - and that gives me a decent nudge toward the computer. I reread everything I’ve written the day before, or even further back in time, and I rewrite the parts that need rewriting. This gets me going and eases me into deeper water.

I don’t sharpen pencils just the right way, don’t line up paper clips in rows or circles on my desk. In writing, I try not to assign meaning to small occurrences or habits and turn them into what they’re not. I don’t disconnect my internet or phone. I like what a great Bulgarian lyrical poet - Damyan Damyanov, crippled by polio all his life - had to say about distractions. “When I’m writing,” he said, “Aphrodite herself can stand before me in the nude and all I’ll do is wave her away. ‘Get out,’ I’ll say, ‘can’t you see I’m working?’”

2. Where do you go to people-watch?

I don’t go people-watching. I also don’t carry a tiny notebook in my pocket nor do I memorize for future use the clever, odd and funny things I hear in my everyday life. Of course I know I should be doing all these things. Maybe foolishly, I hope that sights and sounds and details will find me on their own; that they will seep through my eyes and ears without me realizing, and that later, when I sit down to write, I will relive what I never even realized I’ve lived through in the first place. Perhaps, writing is my proper living; perhaps, I’m like a hamster, who carries the world in his cheeks only to devour it piece by piece later, in the solitude of his little jar.

3. What are your anxieties about language?

I started studying English seriously in Bulgaria at the age of fourteen. Until then I had been especially bad with languages - I’d also studied Russian and Italian and Spanish and couldn’t form the simplest sentence in any of them. I wrote fiction in Bulgarian, published in Bulgaria, and it never crossed my mind that I would have the reason to write in another language.

My life unfolded in such a way that at the age of eighteen I found myself a student in Arkansas. Thinking back to those days, when I struggled for every single word, I grow short of breath, as if something heavy is sitting on my chest. But that struggle for every word proved invaluable. I understood that there are things about writing that transcend language - the honest exploration of a character for instance. Gradually, writing in a language that wasn’t my native [language] transformed itself from a limitation into an advantage.

Last summer I had to translate my stories into Bulgarian, for the publication of East of the Westthere. I was terrified, reluctant to begin. My prose in English is simple; I try to say things as clearly as I can in an efficient and straight-forward way. But this simplicity would not work well in Bulgarian. I was afraid that the voice of every story would fall flat if dutifully translated. I was also afraid that abandoning the original and rewriting the stories entirely would spell disaster - that my superior “control” of the Bulgarian language would tempt me to write sentences that were too flowery.

There is one story in the book, “The Night Horizon,” which tells of a Muslim girl in the Bulgarian Rhodopa Mountains. Her father makes bagpipes for a living and she helps him. When I first wrote the story in English, I wanted the language to evoke the sound of the bagpipe - mournful, monotonous, drawn-out. When it was time to rewrite the story, I realized that such monotony might not work well in Bulgarian. I decided to let the language evoke this time not the sound of the bagpipe, but the sound of the human voice which accompanies it; in other words, in Bulgarian I tried to make the story flow like a Rhodopa song.

4. Is there a character, a scene, a moment that you dream of conveying, but haven't figured out how to yet?

I would like to write a novel about Vasil Levski, Bulgaria’s national hero, truest savior, our Christ really. I’ve figured out the novel’s basic structure, who the narrator will be. But I don’t yet dare put pen to paper. I honestly don’t think I’m old enough to write such a book well. And this has nothing to do with ambition, courage, audacity. There are other books I think I ought to write first. But as another great Bulgarian writer, Nikolay Haytov, says in a famous story of his: it’s one thing to want to do something, and another to be able to do it. Yet a third and a fourth thing to actually do it.

5. What landscape do you most often fantasize about?

Bulgaria. That was the immediate, obvious answer. But then, the more I thought about the question the more I realized the answer wasn’t right. My Bulgaria is not the Bulgaria south of the Danube, west of the Black Sea, north of Greece and Turkey. My Bulgaria isn’t real at all, and I don’t want it to be. It’s not a landscape, because it doesn’t occupy any given space. The other day I looked at the drainage field behind our Texas house and saw in it the meadow my grandfather used to mow with a scythe when I was a kid. In the giant Texas sky I saw the sky my Bulgarian ancestors had seen, fifteen hundred years ago, crossing the steppes on their way to Europe. Maybe I’d overdone it with the instant coffee that day. Maybe it’s a timescape I fantasize about - that of the long gone days, which I believe to be contained within the present and the future, albeit refashioned in different garments.

6. What was the last book you didn’t finish?

Great Expectations. I read the first two hundred pages, and really liked them. Then things happened and I had to set the book aside. But no excuses; I’ve been lazy in picking it up again. Also American Pastoral. I set it aside around the hundredth page, in the middle of a passage that seemed somewhat rambling. Now I feel shame writing this.

7. What are you looking forward to?

I’m too afraid to answer this question. I’m Bulgarian, which is to say a fatalist, superstitious, fearful and pessimistic. The other day, true story this, I found the following fortune in my Panda Express cookie: Keep your plans secret for now.

Back to Top

Author

Miroslav Penkov was born in 1982 in Bulgaria and arrived in America in 2001. His work was included in The Best American Short Stories 2008, edited by Salman Rushdie, and his debut collection, East of the West, was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Categories

Archive

About

A Public Space is an independent, non-profit publisher of the award-winning literary and arts magazine; and A Public Space Books. Since 2006, under the direction of founding editor Brigid Hughes the mission of A Public Space has been to seek out and support overlooked and unclassifiable work.

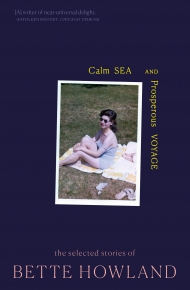

Featured Title

"A ferocious sense of engagement... and a glowing heart." —Wall Street Journal

Current Issue

Subscribe

A one-year subscription to the magazine includes three print issues of the magazine; access to digital editions and the online archive; and membership in a vibrant community of readers and writers.

Newsletter

Get the latest updates from A Public Space.